Introduction

Paper Birch (Betula neoalaskana Sarg.)

Family: Betulaceae

Meaning behind Latin names: Betula possibly comes from the Sanskrit word burga, meaning “a tree whose bark is for writing on,’ whereas neoalaskana means “new Alaska’ (Grey 2011, p. 242)

Other common names: Alaskan paper birch, Resin birch, and Yukon white birch

Botanical Description: B. neoalaskana is a deciduous tree with thin exfoliating papery bark that’s either dark reddish-brown (immature) or creamy white (mature). Twigs are covered with resinous, sometimes large, glands. Its yellowish-green leaves are 1-1/2 to 3 inches long, 1 to 2 inches wide, and deltoid in overall shape with dentate margins. Its tiny nutlets are born out of blunt-tipped, drooping, greenish-brown, 1 to 1/4 inch catkins. The entire tree can grow up 80 feet tall, 4 to 24 inches in diameter and last around the same age of a modern person (80-100 years) (Farrar 2015; Common Trees of Alaska 2009, p. 6).

Habitat and Distribution: B. neoalaskana thrives in slightly acidic and peaty soils. It is found most commonly in northern British Columbia and Yukon to central Alaska.

Chemical compounds: Birch contain a high amount of anti-inflammatory methyl salicylate (salicin) in leaves and branches and antibacterial/antimicrobial betulin in its outer bark (Grey 2011, p 243; Haque 2014.)

Some Uses:

- Footwear — Due to the lightness and malleability, the Inuvialuit people often utilized birch for constructing snowshoes. Elder Sarah Meyook mentioned her grandfather would make them by picking out “the thin branches of young trees, […] peeled of their bark, and cut to length. They were then placed or dipped in boiling water,’ which made them quite flexible (Inuvialuit Nautchiangit 2010, p. 170). Elsewhere, Scandinavian peoples would weave birch bark into shoes, and according to legend, “one could walk a ‘birch bark mile’ (around 9 ½ miles)’ before the shoes fell apart (North House Folk School 2007, p. 54).

- Writing material — Throughout history, different peoples from around the world have use birch bark to write on. The Bakhshali Manuscript, which discussed “the groundbreaking use of zero in mathematical calculations”, dates back to the third or fourth century AD (North House Folk School 2007, p 3).

- Food Storage – According to an Athabaskan birch bark basket maker from Alaska, Sarah Malcolm, birch bark was excellent for storing and wrapping meat and fish, because it prevented the food from rotting: “When they’d kill a moose out in the grass, they’d put [birch] bark down to put cut up meat on. Food not get spoiled on it. Fish good on it. Just like tin foil” (Croft 2013, p. 86)

Folklore:

- Scandinavian — associated with Thor, the god of thunder and of fertility (the rain from thunderstorms helps plants and mushrooms grow). Because of Thor’s place in the hierarchy of gods, birch was said to have protective qualities and its branches were often hung above door frames to ward off evil eye, gout, barrenness, and especially lightning (North House Folk School 2007, p. 78).

- Russian — In the Russian version of Cinderella, The Wonderful Birch, the birch tree serves as the Fairy Godmother and whose branches help the girl to complete tasks, like making clothes for the upcoming festival (North House Folk School 2007, p. 80).

- Ojibwe — The Ojibwe people believe(d) the birch received its water-proof and rot-resistant qualities from the trickster god, Nanabozha, as a reward after sheltering it from angry thunderbirds. The constant crashing of wings, or lightning, from the thunderbirds was said to be the reason for the tree’s markings as well (North House Folk School 2007, p. 86).

Birch Bark Basket

Some ethical wild-crafting considerations:

Removing birch bark is a delicate process. If not done right, the tree can die. If the tree is alive, consult several sources on when the best time to harvest is to ensure regrowth, as the time can vary from year to year and geographical location. Remember to also check who owns the land and possibly getting permission before beginning. Ideally, harvest bark from dead trees (more porous, rougher, and a range of colors) or from trees that are likely to be disturbed in the near future (such as logging or land-clearing operations) (North House Folk School 2007, p. 154, 164).

Supplies:

- sharp knife

- outer piece of birch bark

- slender willow stem (Salix sp.)

- something to punch holes (like the end of a compass)

- few clothespins

- couple thick of sowing needles (with large eyes)

- several yards of thread, such as spruce roots or jute (Corchorus sp.)

- spruce pitch (Picea sp.), (if you want to waterproof the basket); More on spruce pitch here:

Instructions:

1.) Before harvesting from any birch in the area, be on the lookout for the following features to have the best quality in basket: (a) the amount of material you want (multiplying the diameter of the tree by three will give you the width of the piece harvest), (b) how easily the bark comes off (a quick cut vertically with a knife to check), (c) the size and amount of lenticels (the larger and more there are, the higher the risk of tearing), (d) the colors and textures you want, and (e) the presence of scars (which make it harder to work with (North House Folk School 2007, p. 161-163).

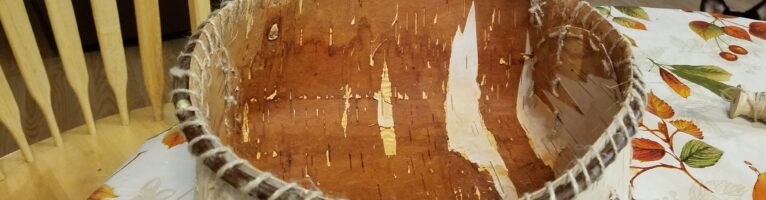

2.) Using your knife, make one cut about an inch through the outer bark near its base. Then continue to cut vertically down. In my case, the vertical cut down was about the foot and half, but some cuts can be a few inches to six feet wide. The tree I picked out (future firewood) also needed a horizontal cut to help with the next step, because it was out of the time frame of harvest (late September rather than June or July).

3.) Peel either half way or completely around (if alive, could kill) the birch tree. For birches are especially ready to be harvested, there’s an audible pop when the outer bark is being removed from the inner bark.

4.) Take the piece back inside and begin working on peeling the layers of cork cambium on the inner side of the outer bark. Keep in mind, this step may take several hours to complete. It’s okay to store the piece for a later day; when you want to use material again, apply water to loosen it.

5.) Using scissors or the knife (if skilled), cut out a bowl-like shape in the middle on both ends of your birch bark piece. The middle sections should be less than the straight flaps (the top and bottom ends in the left photo).

6.) After getting the right size for the mid sections, fold one of them in towards the center and layering the straight flaps over that mid section. Clap a few clothespins to keep all this in place. Do the same for the other end.

7.) Take the jute (or spruce root), feeding it through a needle and weave the flaps and middle sections together. Tie the ends of the threads in knots and remove the clothespins.

8.) Take one end of the willow stem, and either clamp it to the one side of the basket or have someone hold part of the willow. Then, start weaving the jute (or spruce root) through the basket and around the stem as you work around the basket, fastening it tighter and tighter until you’ve reached where you started and tight a knot.

9.) (Optional) Heat up the spruce pitch in a sauce, until it’s in a sticky, liquid state. Let it cool for several minutes, and then apply to seal up any cracks.

A Semi-Structured Interview

About a day ago, I was able to contact Karen Tembreull, a North Michigan basketry artist and a member with the National Basketry Organization, to interview (semi-structured) her about basket making. This interview lasted about 18 minutes in total.

How did you get involved in basketry?

“It was back in 1983 when I was graduating high school. I was an art major, focused in fiber art. Back then, the high schools had a really large art curriculum, unlike today. There was a lot available. I actually had very good classes at that time and at that age and level. In Kalamazoo, Michigan, I also noticed we had a very large adult educational program through the high school and there was a basket making class being taught. Since I was spinning, loom weaving, and other fiber arts like that, I thought it would neat to apply.”

“Shortly after that, that summer of 83, I saw some basket makers at an art show that were using local harvested materials with their basketry and that was what I wanted to focus on. Right away, I started harvesting materials and played with that.”

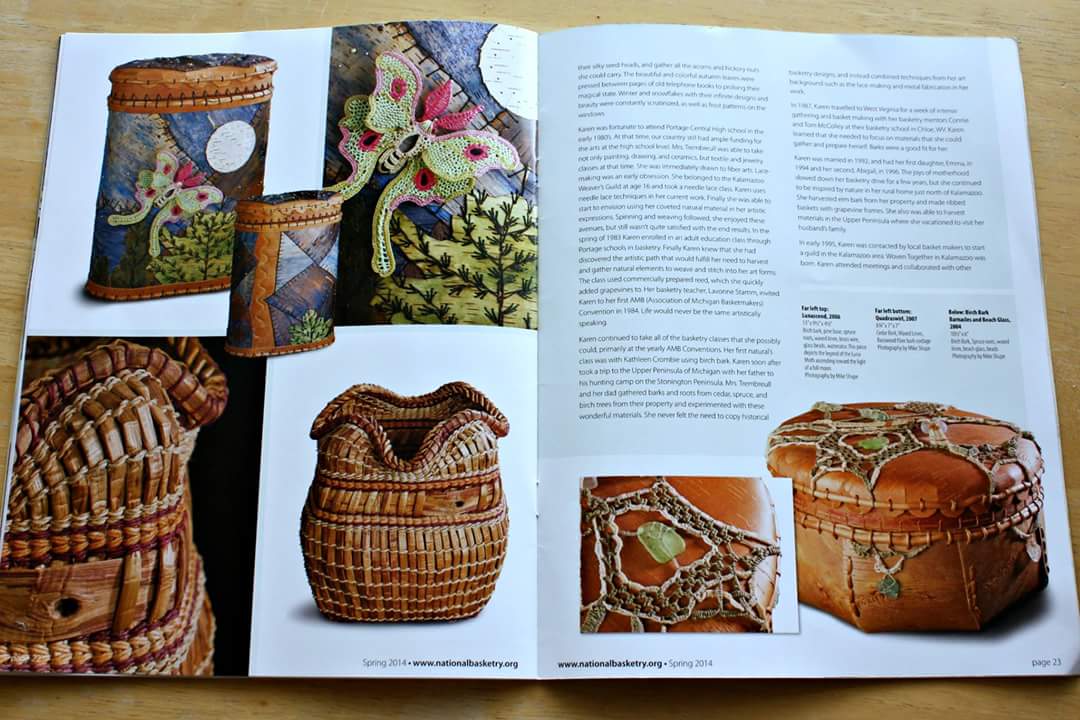

So I recently learned that you were the featured artist of National Basketry Magazine. Could you talk a little about that?

“Well, I am a member of the National Basketry Organization, and they contacted me to write the article, which is a history and synopsis of my work. It was a really great opportunity. It was good to put something like that into words in a chronological order to share with the rest of the basketry world.”

And you’ve been teaching since the early nineties?

“Mm-hmm, it was probably 92. I was a founding member of the basketry guild Woven Together in Kalamazoo. I started teaching just for my guild, because we took turns to teach at our guild night during our monthly meeting. It wasn’t too many years later friends from my guild encouraged me to start proposing for conventions, like Michigan’s and, back then, Indiana. One thing led to another and I started teaching at Michigan convention and moving there to other conventions. And now, I’ve been pretty much all over the country, though certainly not every convention, but I’ve been on the west coast in the last few years. Next year in March, I’ll be at the Los Angeles guild in Julian, California, and in May, I’ll be in Stowe, Vermont.”

And you’ve been teaching ever since?

“Yeah, I have. Not full-time; I still have a day time job where I work part-time at a Veterinary clinic. I still would like to someday, but I haven’t got there yet.”

Is there a kind of basketry you specialize in or is it more general?

“No, I do specialize primarily in barks and roots and anything I can gather locally. The only material I buy on a regular basis that’s commercially prepared is like wax linen or wax cotton thread and recently willow bark from Iowa. Other than that, I like to harvest, gather, and prepare my materials wherever I’m living. In northern Michigan, that’s birch bark, cedar bark, white pine bark, black cherry bark, and elm bark. I also use material that’s called soft rush or Juncus effuses, which grows a lot around here, and grow Siberian or Japanese Iris leaves for twinning. So, I guess I feel strongly that basket makers have historically would use the materials that grew around them and that’s what I like to do.”

What kind of basketry techniques do you use?

“For birch bark particularly, a signature technique for me would be piecing and embroidery, like in quilt designs. I make cylindrical baskets. So, taking a flat piece of bark, I doing this quilting and embroidery on it, and then I join it with a dove tail join. It’ll have a wooden base and a spruce root rim. So that’s what I’m known for doing. But I also work with a lot of different materials and styles, so I’ve never grew up and decided that I’m going to do this one technique (laughs).

[…] The more you work with the material, the more you learn the material. It’s always hard when people want to give me material, because I have a particular way of handling things. Having this relationship with the material is really cool, because you learn what the limitations are, what you can do with it, and when to harvest, how to harvest, how to store, how to prepare.”

And by the end, you probably feel so overjoy that you were able to create this thing from this idea.

“I think it’s pretty cool. I think you’re celebrating the tree and the environment. I guess that’s the Home Ec. magic of it, really.”

So, what kind of pieces have you made?

“So, I’ve made cylindrical patch work ones with wooden bases. I’ll do sculptural things. Recently, I’ve been doing something that’s quite different. I’ve been repurposing antique water supply handles, like spigot handles, from a local plumbing company. I’ve been weaving cedar bark through the openings and using them as a footed base, and then twinning with Iris leaves or soft rush to make softer baskets that way. I do have a Facebook page called ‘Barks & Roots Basketry’ if you want to see some examples.”

Is there a piece you’ve made that you are most proud of?

“That’s a hard one. I did a really different piece that showed well in some shows and not others but I’m quite proud of. It’s a very large oval birch bark container. I actually did some painting on it with acrylic and watercolor washes and some bead work. I also created a lunar moth that sits on it that’s made of a needle lace construction and wired form. It kind of tells a story about the lunar moth, which tries to fly up to the moon. It called ‘Lunacend.’”

References

Bandringa, Robert W. Inuvialuit Nautchiangit: relationships between people and plants. Inuvialuit Cultural Resource Centre, 2010.

Croft, Shannon. Mathewes, Rolf. W. “BARKING UP THE RIGHT TREE: Understand Birch Bark Artifacts from the Canadian Plateau, British Columbia.” BC Studies, Issue 180, p83-122, 1 Dec 2013.

Farrar, J. L. “Alaska paper birch1.’ British Columbia, Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development, Oct. 2003, www.for.gov.bc.ca/hfd/library/documents/treebook/alaskabirch.htm.

Gray, Beverley. The Boreal Herbal: Wild Food and Medicine Plants of the North. Aroma Borealis Press, 2011.

Haque, Shafiul, et al. “Screening and Characterisation of Antimicrobial Properties of Semisynthetic Betulin Derivatives.’ PLoS ONE, vol. 9, no. 7, 17 July 2014, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4102551/.

North House Folk School. Celebrating birch: the Lore, Art, and Craft of an Ancient Tree. Fox Chapel Pub., 2007.

Tembreull, Karen. “Barks & Roots Basketry.” Facebook. 13 Jan 2017. [Accessed 14 Dec 2017. <https://www.facebook.com/123171347846588/photos/a.527239134106472.1073741828.123171347846588/699689510194766/?type=3&theater>]

Tembreull, Karen. “Barks & Roots Basketry.” Facebook. 17 Dec 2012. [Accessed 14 Dec 2017. <https://www.facebook.com/123171347846588/photos/a.123181894512200.26433.123171347846588/123181911178865/?type=3&theater>]

Tembreull, Karen. “Barks & Roots Basketry.” Facebook. 10 Dec 2016. [Accessed 14 Dec 2017. <https://www.facebook.com/123171347846588/photos/a.527239134106472.1073741828.123171347846588/663911900439194/?type=3&theater>]

Tembreull, Karen. “Karen Tembreull.” National Basketry Magazine. Spring 2014: 20-26. Print

USDA Forest Service. Common Trees of Alaska, www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5320147.pdf.

Posted: December 2017