Salves are semi-solid, fatty herbal mixtures made for topical applications, and have been used historically as a medicinal treatment. Hippocrates suggested treating contused wounds with salves to promote suppuration, remove necrotic material, and reduce inflammation.

I started off with the intention of creating a “Yarrow Salve’, but ultimately when it came time to make the salve I wanted to use the dried yarrow sparingly — so I walked around the land surrounding my cabin and picked some lemon balm and plantain as well. Ultimately, I call this a ‘healing salve’ as each plant used has many medicinal properties. I will start with a brief introduction to each plant I used before I guide you through the process of how I made my salve. (Forrest 1982; Gray 2011)

YARROW

Achillea millefolium L.

Yarrow can be ingested as well as applied topically. It has been used as a spice/ingredient in foods, medicinally, and cosmetically. I chose to use it for its medicinal purposes — I knew that the salve would be applied to the hands of someone with arthritis, whose skin dries and splits to the point of bleeding during the winter months. (Geniusz 2015; Gray 2011)

Yarrow has been used medicinally as far back as the Pleistocene Epoch. There is a grave dating back roughly 60,000 years ago, of a Neanderthal who was laid to rest by his people on a bed of medicinal flowers. One of those flowers was yarrow, identified by the pollen that was found in the grave. An attribute to its wound healing capabilities can be found directly in the genus name Achillea — as the great Greek hero Achilles was said to have used yarrow to staunch the wounds of his men. (Geniusz 2015; Applequist & Moerman 2011)

When applied topically, yarrow has been known for its analgesic, antiseptic, and anti-inflammatory properties. Its most common topical uses reported by Native American ethnic groups are for aiding in skin conditions, wounds, and bleeding. It is known to stop the flow of blood from a wound due to its hemostatic compound ‘achilleine’. Yarrow infusions can treat eruptive conditions on the skin such as measles, insect bites, and urticaria. A yarrow-infused oil was used on the hands to strengthen the skin before basket weaving. (Gray 2011; Geniusz 2015; Evergreen.edu 2017; Applequist & Moerman 2011)

PLANTAIN (broadleaf and narrowleaf)

Plantago major L.

Plantago lanceolata L.

Plantain is a common and widely spread plant often seen growing in disturbed areas such as roadways and walking paths. Native to Northern Europe and parts of Asia, plantain has spread all over the world and is often referred to by Native American tribes as ‘White Mens’ Footsteps’ or ‘Whiteman’s Footprint’ (Nozedar 2018; Geniusz 2015).

This herb has been used for centuries to treat illnesses including skin diseases, infectious diseases, problems related to the digestive organs, respiratory organs, reproduction, circulation, and fever. Biological activities attributed to plantain’s effective use as a medicine include anti-inflammatory, antiviral, analgesic, anti-oxidant, anti-cancer, anti-tumor, anti-fever, immune-modulating, and anti-hypertensive effects. In a pharmacological publication by Najafian et al. (2018) properties of the plant were identified to compare modern science with traditional medicinal uses of plantain. “Based on traditional plant medicine (TPM) and modern medicine, this plant has many medical applications in the form of oral or topical, without serious side effects’ (Najafian et al. 2018:6396). The different species of plantain can often be found growing together and are used to treat the same ailments. Leaves of the plantain are both anti-inflammatory and antibacterial; used topically for treating stings, bites, cuts, scrapes, and bleeding. Plantain is effective in treating deep wounds partially due to alkaloids in the plant, which increase the tensile strength of the scar tissue. (Geniusz 2015; Nozedar 2018; Najafian et al. 2018; Haddadian et al. 2014)

LEMON BALM

Melissa officinalis L.

The genus name Melissa means “bee’ in Greek and is related to lemon balms’ historical affiliation with attracting bees and pollinators. “Lemon balm’s lemony flavor and aroma are due largely to citral and citronellal, although other phytochemicals, including geraniol (which is rose-scented) and linalool (which is lavender-scented) also contribute to lemon balm’s scent’ (HSA 2007:7). The medicinal use of lemon balm dates back over 2000 years. This plant has been utilized not only for physical ailments, but has historically been used as a treatment for depression, anxiety, memory loss, and even nightmares. The main active constituents of lemon balm are volatile compounds – and there are over 100 chemical compounds that have been identified in lemon balm. Traditional applications of lemon balm is ingestion or inhalation. The aroma therapeutic use of lemon balm is traditionally for mental and emotional health, where-as the internal use of lemon balm is for physical ailments ranging from diabetes to intestinal ulcers. Topical applications of lemon balm have been used in the treatment of wounds and infections, as the tannins within the plant works as an astringent and contribute to lemon balm’s antiviral effects. My intention of adding lemon balm to the salve was to harness the aromatic properties. (HSA 2007; Shakeri et al. 2016)

SALVE MAKING:

I gathered yarrow leaves and flowers from my lawn while I still lived in North Pole, AK. Given that I wasn’t making the salve until I was relocated to New York, I opted to dry the yarrow using a food dehydrator and store it in a sterilized glass jar until use.

The plantain and lemon balm were gathered the same day that I made the salve, and were used as fresh herbs.

I followed the recipe/instructions for infused oils and salves in ‘The Boreal Herbal’ by Beverley Gray with slight variations of my own being made throughout the process. You can watch a short video of each step HERE on my Instagram story.

I also made a youtube video HERE but unfortunately couldn’t get my original videos to download – so it is a compiled series of still-frames that gives great visual reference.

Equipment/Ingredients Needed:

- Herbs

- Beeswax

- Oil (Sunflower & Jojoba)

- Double boiler

- Wooden spoon

- Steel spoon

- Essential oils

- Strainer

- Cheesecloth

- Grater

- Glass jar

Step 1:

I measured ¼ C. dried yarrow, ¼ C. fresh plantain, and ¼ C. fresh lemon balm and put them in the top of my double boiler. I began to bruise, tear, and garble the herbs to help release the natural oils and create a larger surface area.

Step 2:

I covered the herbs in 2 cups of oil. I chose sunflower oil for its emollient properties, and jojoba oil for its high vitamin E content which helps in the preservation of the salve (Gray 2011).

Step 3:

On low heat, I simmered the herbs and oil in the double boiler for ~1 hour, stirring occasionally with a wooden spoon.

Step 4:

I took the infused oil off of the heat and allowed it to cool to room temperature overnight. Once cooled, I strained the infused oil from the herbs using a cheesecloth and strainer. The herbs were composted and the oil was reserved in a glass measuring jar.

Step 5:

I washed the double boiler and put it back on low heat. The salve recipe recommends adding 2 Tbsp beeswax to every 1 C. infused oil — so I grated 4 Tbsp of beeswax and melted it in the double boiler.

Step 6:

I added the infused oil to the beeswax. Parts of the wax instantly hardened again, but I stirred everything with a metal spoon and allowed the oil to slowly heat up and melt the wax again.

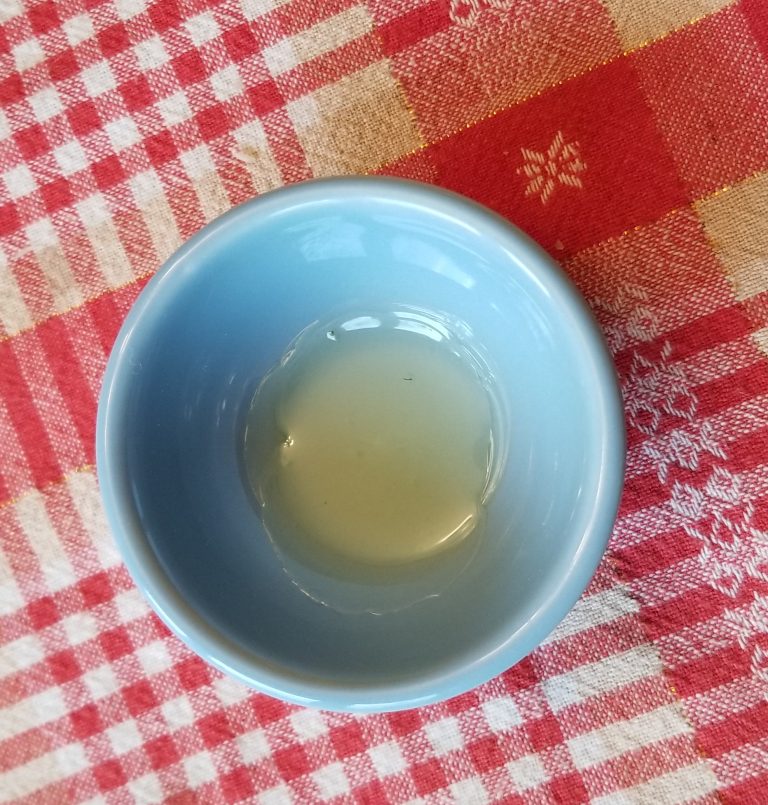

Step 7:

Once everything was mixed well, I took a spoonful of the melted salve and poured it into a small bowl. The bowl was placed in the freezer for 1 minute and then removed — I tested the consistency of the salve with my finger and decided that it wasn’t as firm as I wanted, therefore 4 more Tbsp of beeswax was added to the double boiler and melted/mixed in.

Step 8:

After testing the consistency again, I was satisfied with the result. I then added lemon, citronella, and lavender essential oil to the melted salve. Essential oils will help in the preservation of the salve (Gray 2011). I chose those particular scents, as they are reflective of the scent of lemon balm (and there was no natural scent from the lemon balm in the salve at all).

Step 9:

I poured the melted salve into a sterile glass jar and allowed it to cool and firm up.

Step 10:

Complete and ready to gift or use!

SOURCES:

Applequist, W., & Moerman, D. (2011) Yarrow (Achillea millefolium L.): A Neglected Panacea? A Review

of Ethnobotany, Bioactivity, and Biomedical Research. Economic Botany, 65(2), 209-225. DOI: 10.1007/s12231-011-9154-3

Forrest, Richard D (1982) Early History of Wound Treatment. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 75, 198-205. PMID: 7040656. PMCID: PMC1437561.

Evergreen.edu (2017, January 3) Yarrow: The Healing Herb of Achilles. Retrieved October 26, 2019 from https://sites.evergreen.edu/plantchemeco/yarrow-the-healing-herb-of-achilles/

Geniusz, Mary Siisip (2015) Plants Have So Much to Give Us, All We Have to Do Is Ask. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Gray, Beverley (2015) The Boreal Herbal. Whitehorse, Yukon: Aroma Borealis Press.

Haddadian, K., Haddadian, K., & Zahmatkash, M. (2014) A Review of Plantago Plant. Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge, 13(4), 681-685. URI: https://eprints.muk.ac.ir/id/eprint/1035

The Herb Society of America (2017) Lemon Balm: An Herb Society of America Guide. Kirkland, OH: The Herb Society of America. Retrieved October 26, 2019 from https://www.herbsociety.org/file_download/inline/d7d790e9-c19e-4a40-93b0-8f4b45a644f1

Najafian, Y., Hamedi, S.S., Farshchi, M.K., & Feyzabadi, Z. (2018) Plantago Major in Traditional Persian Medicine and Modern Phytotherapy: A Narrative Review. Electronic Physician, 10(2), 6390-6399. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.19082/6390

Nozedar, Adele (2018) Foraging With Kids. London, England: Watkins Media Limited.

Shakeri, A., Sahebkar, A., & Javati, B. (2016) Melissa Officinalis L. — A Review of its Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry

and Pharmacology. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 118, 204-228. DOI: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.05.010

Posted: November 2019