Introduction

For some time, I’ve wanted to tap trees for sap, but I don’t have any tap-able trees in my yard. Land access, and access to the variety of plants living on different lands around us is a significant challenge, much more for some people than for me. As a white settler on Dakota land with unearned class and racialized privileges, I’m fortunate to be a homeowner and to have long-term, friendly relationships with my next-door neighbors who also own their homes.

So I asked my neighbors who have boxelder trees and a hackberry tree, and they agreed to let me tap them, but for various reasons, we didn’t end up with any sap: one boxelder tree said no, the season wasn’t good for the one shady boxelder that we did tap, and the hackberry didn’t produce any sap (and someone stole the bucket from the tree!).

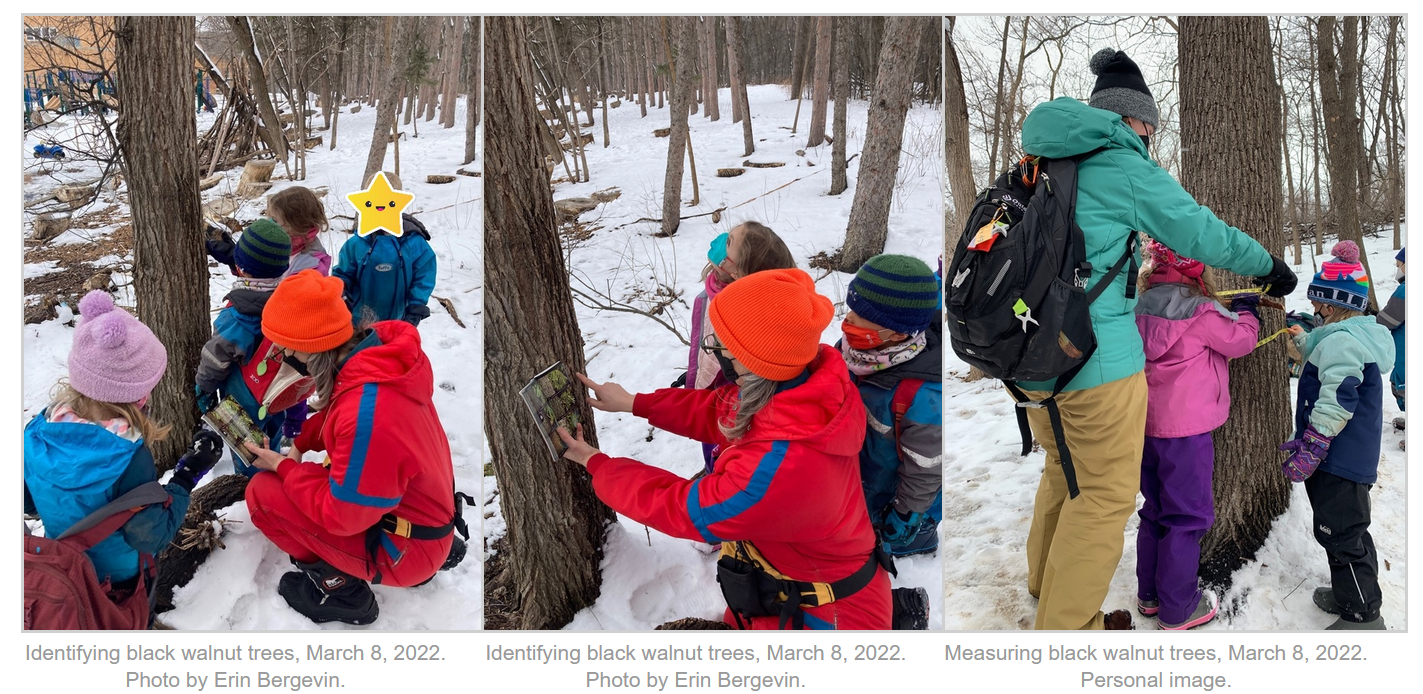

My kid goes to a nature preschool which is on land designated as a school forest, which means it has its own management plan and access rules. I was able to get permission from the school director to tap some black walnut trees in the forest, and to involve the preschool children in the process, so I will be sharing about that experience. But first, a little background about black walnut trees.

Juglans nigra / black walnut botany

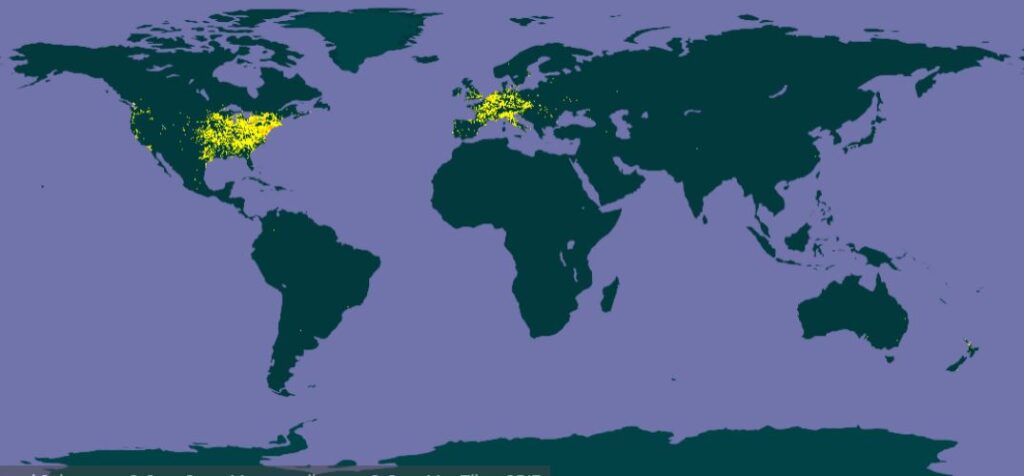

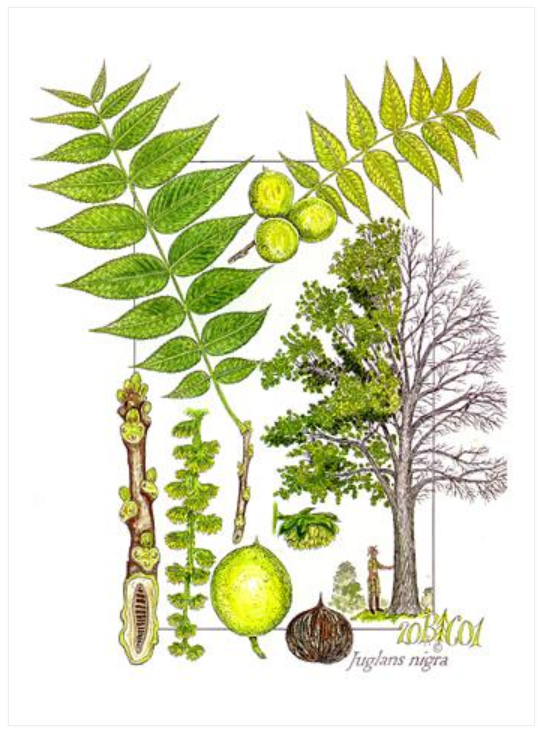

Black walnut, or Juglans nigra, is a deciduous hardwood tree native to Eastern North America, primarily in the United States, and it has also naturalized in some areas of Europe. It is a member of the Juglandaceae plant family.

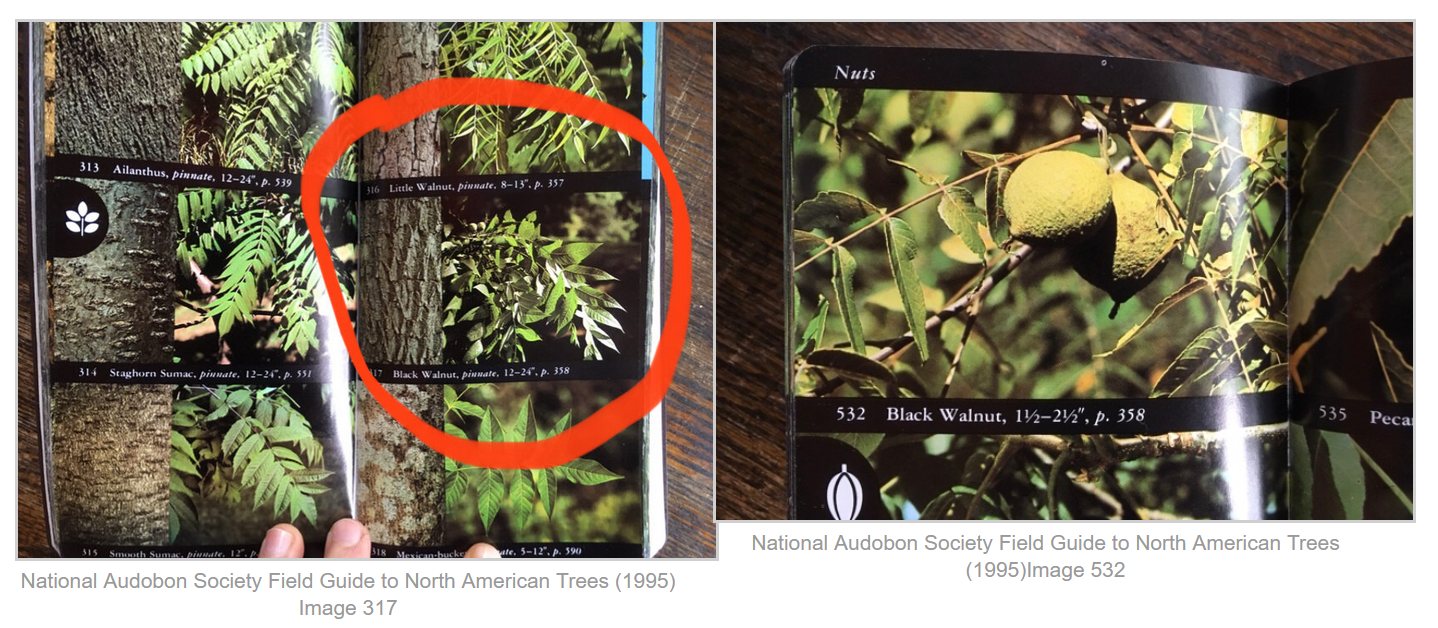

Mature trees stand an average of 70 to 90 feet tall with a diameter of two to four feet. They are fast growing, reaching their peak height at around 30 years, and starting to bear fruit at around 10 years (Michler et al. 2001: 191). Black walnut leaves are pinnately compound, with anywhere from 9 to 21 leaflets (Little 1995: 358–59).

The bark is dark brown with deep furrows often forming a diamond pattern. Black walnut’s preference to grow in sunny areas with well-drained mesic soils lead to a typically straight and vertical trunk habit. The tree sends down a deep taproot (Michler et al. 2001: 189). The twigs have a chambered pith that is visible if you were to cut a branch lengthwise.

One of black walnut’s most identifiable features are its fruit, growing singly or in pairs with a thick green-turning-brown husk covering a sweet, edible drupe, colloquially referred to as a nut. The trees are allelopathic (inhibiting growth) because they produce juglone which can be toxic to some plants attempting to grow nearby, including lilacs, lilies, apples and plants in the nightshade family (Michler et al. 2001: 189).

Black walnut trees need ample sunlight and mesic soils. Consequently, they prefer to be on the forest edges, often near maples, poplar, oak or beech (Michler et al. 2001: 189). A 1989 study about nut-bearing trees’ intrusion into prairie lands looked specifically at the success rates of black walnuts that were cached by fox squirrels and then grew into trees. Black walnuts can be about 10% of a fox squirrel’s diet, so the two species’ abilities to thrive are deeply connected. The study found that seeds that were buried within 10 feet of other trees had much lower germination and survival rate, but those planted in the prairie were more successful, hence the black walnut’s tendency to be at the forest edge (Stapanian and Smith 1986: 331).

Black walnut ethnobotany

I live on Dakota land, and the word for “black walnut” in the Dakota language is hma, while “black walnut tree” is hma hu (because ‘hu’ means ‘legs,’ so a black walnut tree is the legs of the black walnut). The Lakota words for black walnut are gmá or čhaŋsápa, the latter word from čhaŋ –“wood” and sápa – “black” (Austin 2004: 375; Black Elk and Flying By Sr. 1998: 23).

Humans have historically used different parts of black walnut trees for different purposes. According to ethnobotanist Daniel F. Austin, the tree has antiseptic, antifungal, and herbicidal properties, its tannins can be used as an antibiotic, and it contains anti-tumor lectins and ellagic acid (2004: 377). The bark has been used medicinally for toothaches, headaches, snakebites, and, as a weak decoction for treating diarrhea, though it has been found to be toxic so caution must be applied (Austin 2004: 376; Black Elk and Flying By Sr. 23). To treat skin ailments like eczema, poison ivy or herpes, Lakota people would make a poultice our of the bark and leaves (Black Elk and Flying By Sr. 1998: 23).

The juice from ground black walnut husk has been used topically to treat ringworm by Lakota communities, whereas the Comanche used the leaves for the same purpose, and the Delaware used the leaves as an insecticide against fleas (Black Elk and Flying By Sr. 1998: 23; Michler et al. 2001: 189). Interestingly, ground black walnut husk is also used as an abrasive product, and I have recently seen scouring pads made from them at my grocery store (Michler et al. 2001: 191). The only reference to sap use that I found was from Gladys Tantaquidgeon’s Folk Medicine of the Delaware and Related Algonkians, where she wrote that it was used as a topical application for inflammation (2001: 29).

The seeds are edible and delicious, and enjoyed by humans and other wildlife. Commercial nut production has led to the development of more than 700 cultivars, many of which are grown for their increased edible kernel size and flavor. Nutritionally, the nuts are high in omega 3s, unsaturated fats, protein and fiber, while being low in saturated fats, cholesterol and sugar (Michler et al. 2001: 191).

Because of its tannins, black walnut trees are also a strong dye plant, with different communities using the bark, roots, leaves and/or nuts to stain or dye (Michler et al. 2001: 189). Working with the nuts will also stain your hands.

Commercially, black walnut’s biggest role is in the timber industry, as its hardwood is amongst the most valuable lumber today, often used in cabinetry and furniture making as well as for musical instruments and gunstocks (Michler et al. 2001: 191; Farrell 2013: 50).

Tapping black walnuts for sap and syrup

The first academic research I read on tapping black walnut trees for sap was from 2003 to 2004 in Kansas, at which point they listed no known commercial black walnut syrup production (Naughton et al. 2006: 214). Since that time, especially after the publication of Michael Farrell’s book The Sugarmaker’s Companion: An Integrated Approach to Producing Syrup from Maple, Birch and Walnut Trees in 2013, more people have begun tapping black walnut trees for home or commercial use.

Syrup-making from black walnut trees is still being studied, specifically by Mike Farrell and the team at Cornell University and by Future Generations University’s Dr. Michael Rechlin, as they see promise in black walnut’s resilience in a changing climate (Farrell 2013: 300). To answer a larger question about how black walnut syrup can be further commercialized, one of the main areas of study is the timing of black walnut sap flow. Maple and birch are far more commonly tapped for syrup, and much more is known about the processes that work well for them (Farrell 2013: 300).

While maple and birch are both diffuse porous trees, they have different physiological triggers for their sap flows and consequently they should be tapped at different times of the spring. Maples exude sap because of a pressure build up when you have a significant temperature difference between a cold tree and the warmer ambient temperature. Birch sap flow is dependent on root pressure created when the soil temperature warms, so birches are typically tapped after maples have finished producing. The current research shows that black walnut sap flows via both of these means, but most people currently tap black walnuts at the same time as maples (DeVries; Rechlin and Herby 2020: 2; Farrell 2013: 52).

Other research as shown that black walnut sap flow is highly dependent on temperature and wind (Naughton et al. 2006: 219), and that it could be beneficial to tap younger black walnut trees instead of older trees, because the younger trees have a greater percentage of sapwood, which turns to heartwood as the trees mature (Farrell 2013: 50–51). Commercial producers already in the maple syrup industry are interested in research emphasizing vacuum-assisted sap flow (Farrell and Mudge 2014: 36).

In a 2005 study, consumers preferred the taste of Log Cabin brand syrup over both real maple and black walnut syrups, but the researchers concluded there could be a niche market in black walnut syrup (Matta et al. S612). A recent query on the Black Walnut Syrup Makers Facebook group bears that out, showing that the average price for finished black walnut syrup is $3 to $6 per ounce, while real maple syrup sells for $.19 to $.40 per ounce (Norris 2022).

*But is it good for you?

Probably not! Though a study from Southern Poland evaluated the mineral content in the sap from eight different tree species, and one liter of black walnut sap could provide 100% of the recommended daily allowance of copper, 3-6% of the daily recommended intake magnesium and trace amounts of potassium and calcium (Bilek et al. 2016: 676–77).

*But could it be bad for you?

Researchers were also interested in the question of whether people who are allergic to walnuts would also have allergic reactions to finished black walnut tree syrup; the good news is that their findings showed the syrup is not allergenic (Lierl et al. 2020: 3).

What makes tapping black walnuts commercially more challenging than maple?

Black walnut trees do not grow in dense stands the way maples can; as stated above, they prefer to grow on the forest’s periphery, so a sugarbush operation will not be able to have as many taps per square foot of land (DeVries). People may not want to tap their black walnut trees because they are valuable for lumber and each tap hole permanently stains the wood (Farrell 2013: 50). Black walnut sap also contains a significant amount of pectin, which can make the boiled sap have more of a jelly-like consistency and can clog filters and reverse osmosis systems (Farrell and Mudge 35–36; DeVries).

The project

Luckily, I’m not a commercial producer! When the daytime temperatures had warmed and I acquired some more sap collection materials (since mine were in use in my neighbors’ boxelder and hackberry), I set up a time to tap the trees at the Anwatin Forest at Bryn Mawr Elementary and Minneapolis Nature School.

I wrote up a short curriculum description that I have shared with Minneapolis Nature School so they can refer to it if they want to tap black walnut trees in the future, and it describes the early stages of the process well.

Black Walnut Tapping for Minneapolis Nature Preschool, March-April 2022

Sap for Black Walnut, Boxelder and Maples will flow best when temperatures are close to 40 degrees in the day, and below freezing overnight. Alternating freeze and thaw temperatures are necessary to create the hydraulic pressure which causes the sap to flow when the tree is tapped. Once temperatures stay above freezing and trees bud, the tapping season is over.

Mid- to late-February:

- Identify trees to tap

- Gather supplies:

- Sap Collection bucket/bag/bag holder(s)

- Spile(s)

- Drill with appropriate size drill bit for the width of your spile

- Hammer or mallet to tap the spile into the tree

- Something to offer to the trees to say “thank you”

- Measuring tape

- Tree Identification book/field guide/pictures

- Large food-safe bucket/jug/jar with lid if you will need to store sap before boiling, or if your sap collection containers become too full before flow stops

With Students on a warm enough day (to have your hands exposed while drilling/tapping), early- to mid- March

- Talk with students about tree identification, which trees produce sweet sap.

- Talk about what the sap does for the tree, why it flows at this time of year.

- Ask who has had maple syrup, who has tapped a tree, how do we turn the sap into syrup.

- Make sure the tree is wide enough. When we tapped this year, I was going off of the maple information which says the trees should be at least 12” wide. But I read a study specific to black walnut that says you can tap them when they are smaller without causing harm, and you may actually get more sap because they have less sapwood and more heartwood as they age.

- Trees 16”+ in diameter can have more than 1 tap, but the taps should be spaced ~8” apart from each other horizontally, not vertically aligned. This year we used something we knew was about 12” like an adult boot to see if the tree was wider than the boot. We also found a stick and held it across the tree width-wise and measured the width on the stick with a tape measure.

- Ask the tree if we can drill a hole to take some sap to boil into syrup and listen for a response, then respect what you’ve heard.

- Offer something that is meaningful to you in gratitude for the tree sharing its sap (this year we offered songs, bird seed, and some dried herbs like anise hyssop and bee balm/monarda).

- Choose a spot where the bark is clear enough to drill into, preferably on the South side of the tree where it will receive the most warmth from the sun, about 30-48” up from the ground. Look for any previous tapping holes and try to be at least 1-2” away horizontally. Don’t tap directly above/below any previous holes because the column of sapwood above and below the old hole will be blocked by the healing of the wound.

- Drill a hole as horizontally as possible (or drill in at a slight upward angle), 1.5” – 2” into the tree.

- Remove any sawdust from the hole to prevent it from blocking the sap flow. The sapwood should be a pale whitish color.

- Use a hammer to tap the spile into the tree. It is set deep enough when it makes more of a thud sound when you pound it in; it doesn’t have to go in very deep.

- Hook your bucket, bag or other sap collection container onto the spile.

Monitor your collection to make sure it’s still all in place (hasn’t fallen off or developed any holes!), emptying when needed and getting curious about which days/weather conditions produce more sap, which days produce less. Sap flow is often for 4-5 weeks but depends a lot on the season’s weather.

- At the end of the sap season, when sap stops flowing and the trees are budding, remove the spile so the tree can begin to heal that wound.

- If you’re going to attempt a second tap in the season, choose a new spot to drill a hole and follow the same steps as above, waiting until the birch sap is flowing. This year I noticed the black walnut at the top of the hill was flowing first, because its ground had warmed earlier than the middle and bottom of the hill trees.

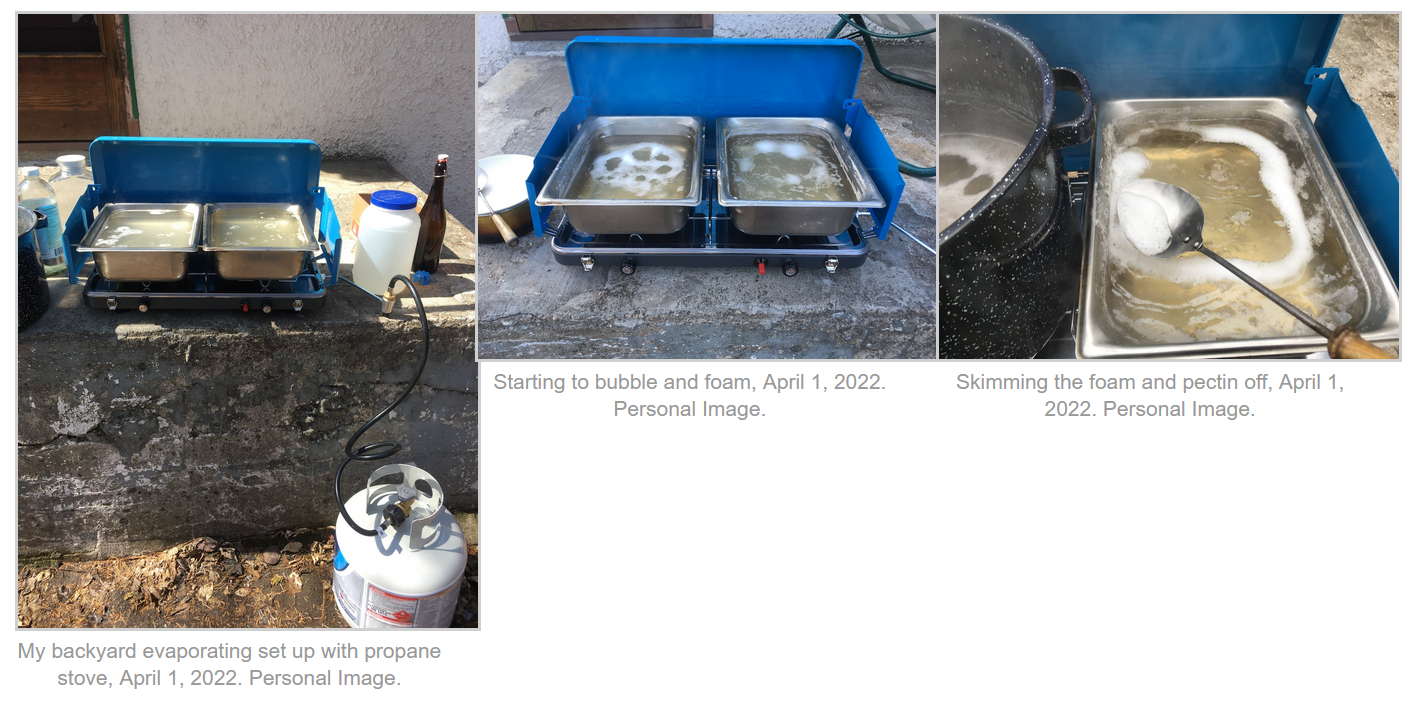

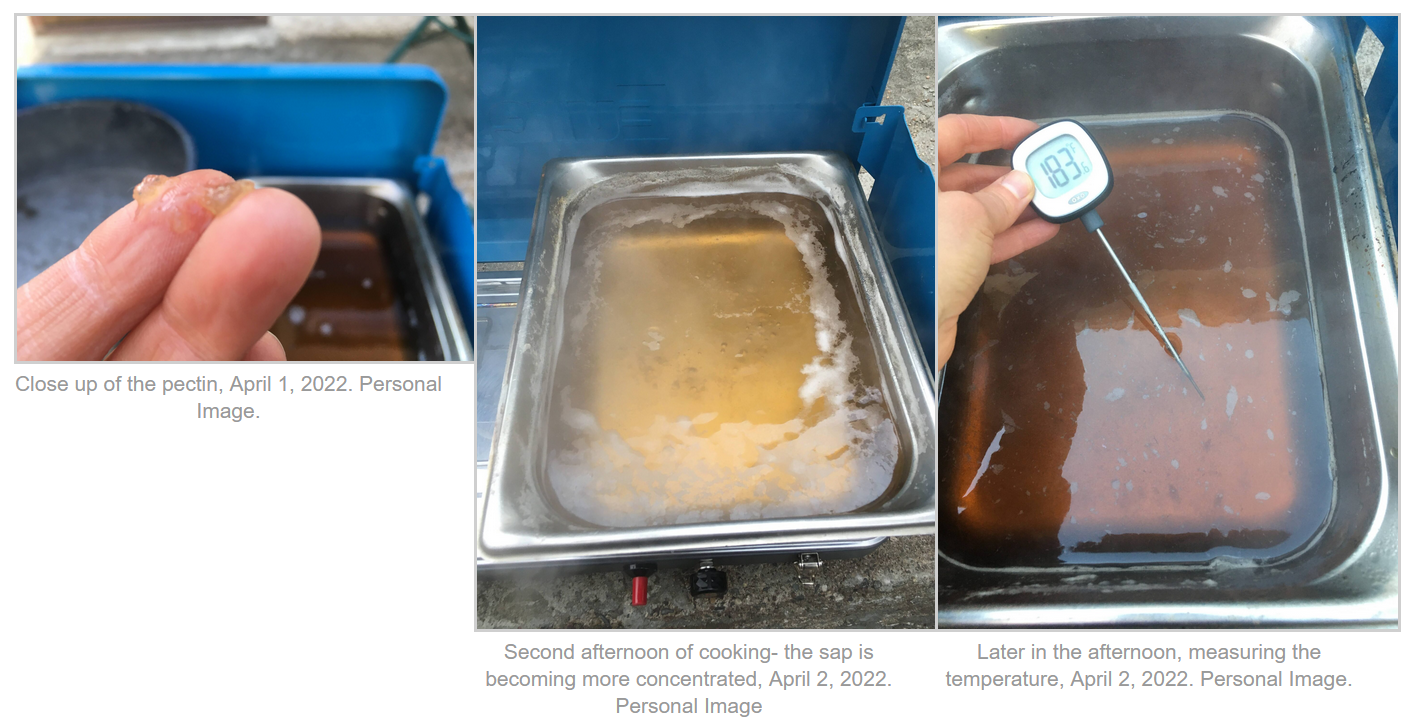

Boiling

Follow the same process you would for boiling maple syrup, however, note that black walnut sap contains higher amounts of pectin. I found it helpful to skim the foam and jelly-looking bits from the black walnut consistently while it was cooking down, and didn’t find that the syrup turned into jelly in the end. You can even save what you skim off and spread it out in a dehydrator to have powdered pectin you can use for later jelly-making projects.

- For now, people are using the boiling temperature of maple as true for the boiling temperature of black walnuts, that is 7 degrees above the boiling temperature of water, so 219 degrees Fahrenheit for us lowlanders.

- I didn’t measure brix or use a hydrometer for this syrup, and I didn’t do any extra filtering beyond the first straining when I poured it into pans to begin boiling.

- The sugar content of the sap can vary greatly between individual trees, and times of the season, so there hasn’t been an established standard yield for black walnuts. This year our sugar content must have been close to 4% because our rate was about 20 gallons of sap for 1 gallon of syrup, which is a great yield!

Boiling and finishing the syrup

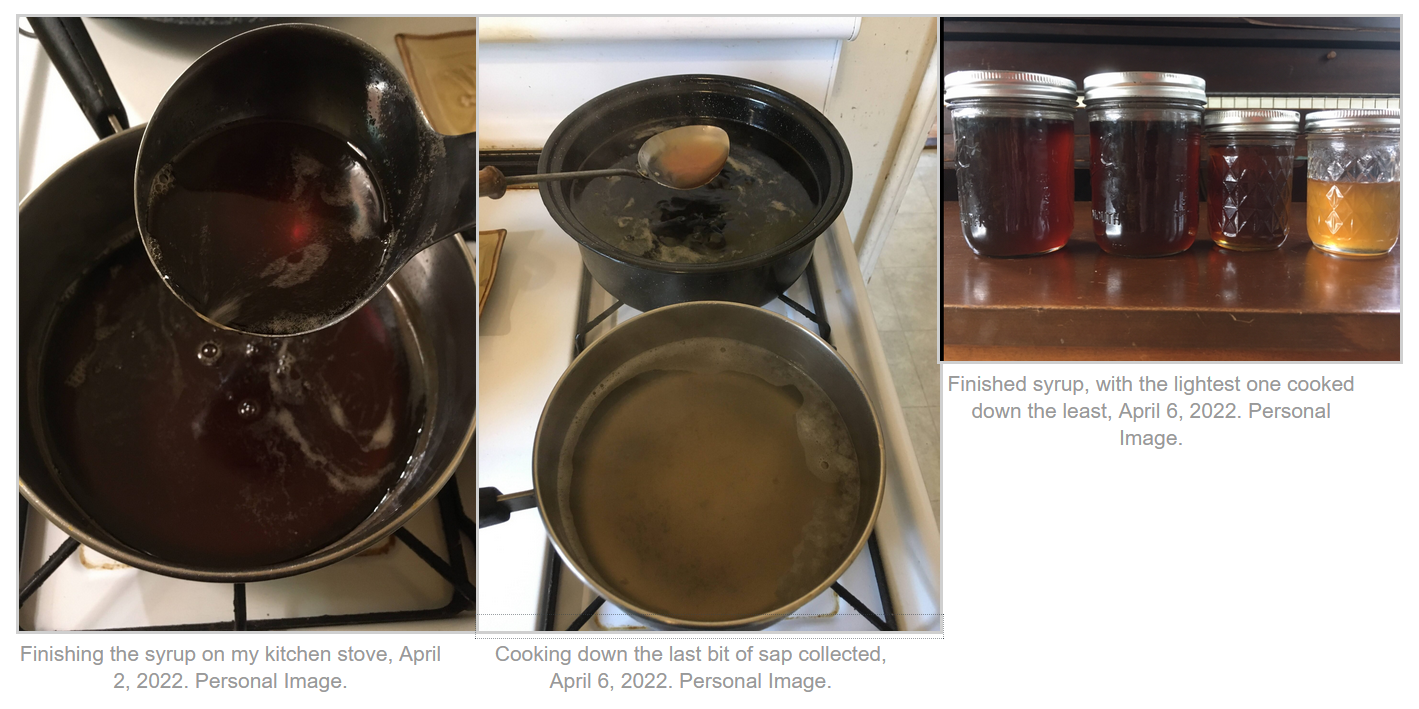

Between March 8 and April 11, we collected about 9.5 gallons of sap, from three trees. I kept the sap in jugs in my refrigerator and in a bucket outside in a shed to keep cool until I had time to boil, and then set up a two-burner propane stove with two steam table pans/chafing dishes and started to boil. Unfortunately, I was not able to share this process with the preschool kids because of safety concerns, and it is also not all that interesting to watch sap boil for many hours. It took me two afternoons at about 5 hours each time until it had reached an amber colored syrup consistency. I finished it on the stove in my kitchen, and at the same time cooked down the remaining sap that had flowed in the few days since I did the outdoor evaporating but evaporating it less, giving us a lighter, slightly less sweet syrup.

The Interview

I wanted to speak with someone local with experience in making black walnut syrup. Fortunately, Richard DeVries who manages the maple and black walnut sugarbush at the MN Landscape Arboretum agreed to not only spend time talking with me, but to let me share a video of our conversation as well.

Project Costs

3 spiles ($7.50)

5 sap bags ($5)

3 bag holders ($21)

I already had a drill and drill bits, chafing dishes, jugs, buckets, the propane stove and fuel and canning jars, and I was driving my kid to preschool anyways so I didn’t have to spend extra gas money to go collect the sap very often, so my total expenses were $33.50.

Project Complications and Future Research

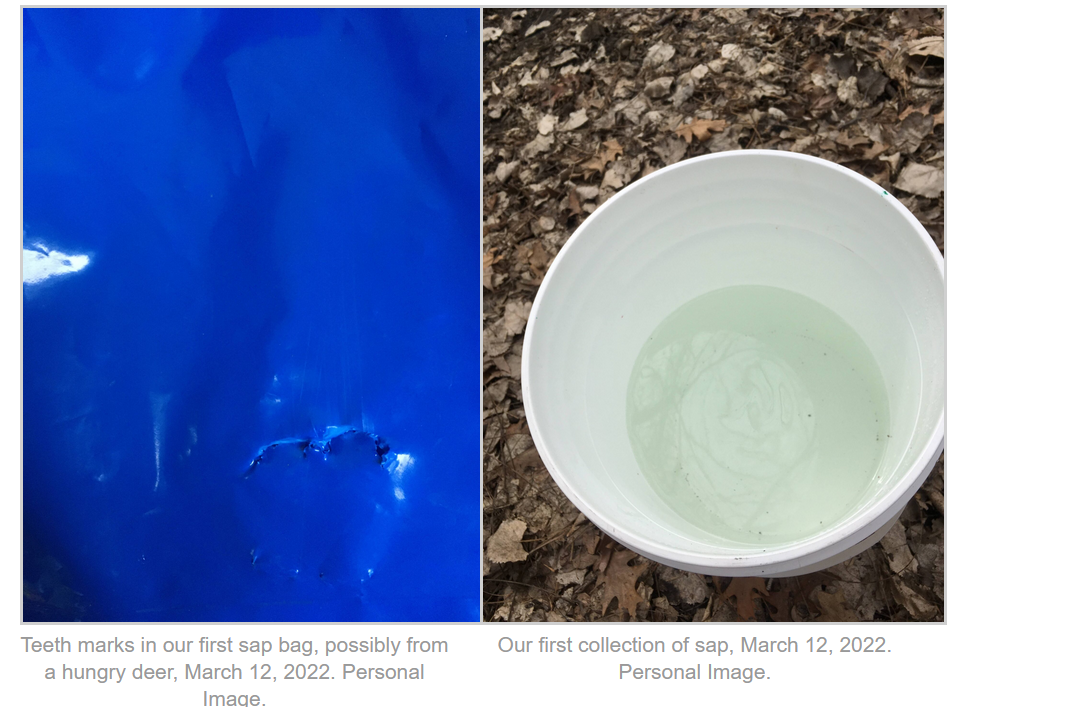

School forests are really great, and offer the flexibility to harvest from the land in a way that some other public lands do not. I was a little concerned because it is a public space in the city, that the spiles and bags I put out would walk away (full of sap!) but they didn’t (unlike the bucket I had to collect sap from my neighbor’s tree!). I had one issue because my spiles were too long for the bag holders that I found, so it dripped out the opposite side instead of into the bag, and another issue where someone…a deer?…bit a hole into one of the bags, but other than that, the creatures that share the school forest left the taps and bags in place and the collection was fairly simple.

I have tapped the black walnuts a second time, as of April 20, 2022 and one of the three trees was flowing with sap again. This is when birch trees’ sap is flowing here and I am curious to see what kind of volume and flow we notice from this second tap of the season.

Acknowledgments

I owe many thanks to the Dakota people who continue to steward this land, the staff and students of Minneapolis Nature Preschool, Richard DeVries and the University of Minnesota Landscape Arboretum, Matt and Ellar for helping me with sap collection and processing, and the black walnut trees and other creatures in the Anwatin School Forest.

Works Cited

Austin, Daniel F. “Florida Ethnobotany.” Google Books, CRC Press, 2004, pp. 375–77, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Florida_Ethnobotany/7qgPCEiI4WMC?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Bilek, Maciej, et al. “Mineral Content of Tree Sap from the Subcarpathian Region.” Journal of Elementology, vol. 21, no. 3, Polish Society Magnesium Research, 2016, pp. 669–79, doi:10.5601/JELEM.2015.20.4.932.

Black Elk, Linda, and Wilbur Flying By Sr. Culturally Important Plants of the Lakota along the Missouri River, Pre-Oahe Dam. 1998, https://puc.sd.gov/commission/dockets/HydrocarbonPipeline/2014/HP14-001/testimony/betest.pdf.

DeVries, Richard. “Interview.” By Interviewer Caitlin Cook-Isaacson, 23 Mar. 2022.

Farrell, Michael. The Sugarmaker’s Companion: An Integrated Approach to Producing Syrup from Maple, Birch, and Walnut Trees. Chelsea Green Publishing, 2013.

Farrell, Michael, and Ken Mudge. “Producing Syrup from Black Walnut Trees in the Eastern United States.” Maple Syrup Digest, 2014, pp. 33–37.

Lierl, Michelle, et al. “Black Walnut Tree Syrup Is Not Allergenic in Individuals with a Documented Walnut Allergy.” Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice, vol. 8, no. 6, American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, June 2020, pp. 2096–97, doi:10.1016/J.JAIP.2020.01.061.

Little, Elbert L. National Audobon Society Field Guide to North American Trees: Eastern Region. 15th print, Alfred A. Knopf, 1995.

Matta, Ziad, et al. “Consumer and Descriptive Sensory Analysis of Black Walnut Syrup.” Journal of Food Science, vol. 70, no. 9, 2005, pp. S610–13.

Michler, Charles H., et al. “Chapter 6: Black Walnut.” Genome Mapping and Molecular Breeding in Plants, vol. 7, 2001, pp. 189–98, http://www.black-walnuts.com.

Naughton, G. G., et al. “Making Syrup from Black Walnut Sap.” Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science, vol. 109, no. 3/4, 2006, pp. 214–20, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228625023_Making_syrup_from_black_walnut_sap.

Norris, Amanda. Question to Black Walnut Syrup Makers Facebook Group about pricing. Facebook, 9 April 2022, 5:21pm, https://www.facebook.com/groups/2965351326865418. Accessed 20 April 2022.

Rechlin, Mike, and Christoph Herby. Walnut-Observations on The Timing of Tapping 2020 Sap Flow Season. 2020, www.Future.Edu.

Stapanian, M. A., and C. C. Smith. “How Fox Squirrels Influence the Invasion of Prairies by Nut-Bearing Trees.” Journal of Mammalogy, vol. 67, no. 2, Oxford University Press (OUP), May 1986, pp. 326–32, doi:10.2307/1380886.

Tantaquidgeon, Gladys. “Folk Medicine of the Delaware and Related Algonkian Indians.” Google Books, Fourth Edition, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 2001, p. 29, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Folk_Medicine_of_the_Delaware_and_Relate/-xlxH4_nufQC?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA2&printsec=frontcover.

Project created in EBOT 251, spring 2022.