At the beginning of the year I was shopping in an antique store and found two pine needle baskets. They were beautiful so I took pictures for inspiration and was fortunate enough to have the opportunity to make my own as my first project for this class.

Pine Needle Basket

Photo by author

1/2/20

Pine Needle Basket Siding

Photo by author

1/2/20

I started my research by watching a youtube video where a mother and her son make a basket using pine needles and raffia. It seemed simple enough – so I decided to go ahead and try my hand at basket making! (again!)

Pinus strobus L.

Photo by author

2/21/20

I certainly am no arborist, but after reviewing The Sibly Guide to Trees, I am going to make an educated guess that I am working with an Eastern White Pine (Pinus strobus L.). Identifiable markers of this species include long, horizontal branches, cones without prickles, and slender needles in bundles of five (roughly ~4inches long) that form triangular clusters angled towards the branch tips. In her book, Plants Have So Much To Give Us, All We Have To Do Is Ask, Mary Geniusz gives a helpful tip that the English word “white” has five letters, and the white pine has five needles in a bunch. Mary Geniusz further describes the white pine tree as a graceful and refined woman – her bark is tight, smooth, and gray – like an elegant dress. Her sap is thin and strong, running down the bark and drying in white streaks against the trunk instead of drying in clumps like other conifers.

Triangular clusters of needles.

Photo by author

2/21/20

Roughly 4″ length pine needles, clusters of 5.

Photo by author

2/21/20

The pine family (Pinaceae) includes about 250 species with 7 genera. The genus Pinus include about 115 species of trees (and sometimes shrubs), and can be separated broadly into two groups – white pine and yellow pine. These groups are named for the color of their wood – they can interchangeably be identified as hard wood or soft wood pines, again, referring to properties of the wood. Pines are distinguishable from other general by their long, 2-5 clustered needles, and woody cones with thickened scales at the tip. (Sibley, 2009)

Pines are monoecious – producing both male and female cones. They produce large crops of fruit every three to seven years, which is thought to help thwart seed scavenging by animals and birds. ‘Flowering’ occurs between May and June in the Northeastern regions of North America (where Eastern white pines grow). The male cones develop several weeks before the female cones, and these trees typically bear female cones after maturing 5-10 years. White pines do not vegetatively reproduce in natural conditions. (Sibley, 2009; Burns & Barbara, 1990:479-481)

From an economic standpoint, pines are high on the list. Their wood is used for lumber, pulp, and white pine tar (which is used as an antiseptic, expectorant, and protective). The wood has medium strength, stains well, finishes well, and can be worked easily – a reason for it to be commonly used in furniture, matches, and many other items. White pine was the prime lumber tree in colonial times. The British Empire utilized white pine to build their ships and used full-sized white pines as the masts. The pitch is used to make turpentine. The white pine is also cultivated for Christmas trees as its foliage as good color and it responds well to shearing. It is a rapid growing northern forest conifer, so it bares well as an excellent tree for reforestation projects and landscaping. (Sibley, 2009; Burns & Barbara, 1990:485; Geniusz, 2015:85).

The cones, inner bark, and seeds are all edible. The inner bark can be dried and powdered to be used in baking as a flour substitute or thickening agent. The inner bark, needles, and pitch are used for medicine. The bark is used as an astringent and an expectorant, making it extremely efficient in relieving symptoms of respiratory tract conditions in which mucous and wet coughs occur. The pine needles have a high vitamin C content and can be made into a tea or infusion to aide in the recovery from colds or the flu. The pitch can be purified and used to treat wounds as well as sore throats. Pine needle extract is currently being researched for its efficacy on treating amnesia. It is important to remember that each species of pine tree has a varying compounds, oils, and other nutritional or pharmacological properties. (Lee et al., 2015:1-3; Sing et al., 2018:10350; PFAF, n.d.: para. 3)

I live in the indigenous land of the Haudenosaunee peoples. The white pine is considered a national symbol to the five nations, and is called the ‘Tree of Peace’. The tree plays a major role in the story of the warring nations of the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca, became united under one law as Iroquois. A man name Peacemaker had a vision of a great white pine tree, with the weapons of war buried at its roots. Four white roots spread from the tree in four directions, and anyone who followed the roots to the base of the tree found shelter. At the top of the tree was an Eagle who warned the people of any danger. The white pine is the only five-needled tree in New York State, and has been used by storytellers to explain the ‘bundling’ of the five nations. The white pine is often symbolically represented in the creation story of the Haudenosaunee peoples, depicted growing on the back of a snapping turtle. (Patterson, 2013:15)

Given its significant cultural use and symbolism, along with its massive deforestation due to early logging industry demand, indigenous communities (such as the Algonquin) are calling for restoration and sustainable management of white pine on their ancestral territory. The community participated in informational interviews which helped address its important role in traditional life as well as a resource for goods and services. These interviews highlighted white pines integral role in cultural stories, medicine, cultural landscapes, and providing habitat for flagship wildlife species. It is important to include social and cultural values in forest management decisions, and incorporate traditional forest-related knowledge that can assist in guide resource management. (Uprety, Y., Asselin, H., & Bergeron, Y., 2013:544-550)

When considering pine needle basketry, all pine species can be used – however – trees with long needles such as the long leaved pine (Pinus palustris) and the slash pine (Pinus caribaea) are preferred. The best time to gather needles is in late spring or summer just after they have matured to their full length, but before any insects have deposited eggs on them. Needles can be cured in sunlight to produce a rich golden brown color, or can be cured away from sunlight to help retain its original color. If curing the needles, you can pull them off individually from a branch, or pull the branch entirely. Keeping the needles on the branch allows for easy turning during the curing process. Cured needles should be boiled in water to kill any eggs that may hatch. When weaving with cured needles, they should be dipped in water for several minutes and kept on a damp cloth throughout the basket making process. (Todd & Breen Del Deo, 2017:111-113)

BASKET MAKING:

I feel that basket making is best taught through simulation/demonstration. Therefore I decided to record my venture into pine needle basket making. I broke it down into simple steps and did my best to add information as I went along that I thought was useful and encouraging. You can watch my video HERE.

I gathered several small branches from the base of the tree. I then pinched the needle clusters off of the branch and sorted them – any clusters that had severely browned/dried needles, missing needles, or broken needles, were returned back to the woods. I then took the needles that I kept and soaked them in a bowl of warm water for about 1hr. They were green and fairly pliable, so I do not think that soak time truly matters as long as they are kept wet before being manipulated.

Gathered pine branches

Photo by author

2/21/20

Damaged pine clusters Photo by author 2/21/20

I then laid out all of the materials I would be using. In total I had:

- 1 medium sized bowl (filled with warm water)

- sorted pine needles

- tea towel

- scissors

- embroidery needle

- sinew

Purchased materials

Photo by author

2/21/20

I started off by taking 15 clusters of needles (5 needles per cluster) and lined them up at their joints. I then wrapped the sinew around the joints and down the clusters – creating a bundle – to about 1/2 inch. I then turned he bundle over itself, coiling the needles and wrapping sinew to hold it in place. Once I was coiling a third row of the needle bundles, I began to stitch the sinew through the previous row, rather than wrapping. As I was reaching the end of my needle bundle, I created new bundles of roughly half the diameter (7 clusters) and stitched them into the ends of the previous bundle. This continued until I felt that I had formed a decent diameter base for my basket.

Starting the base

Photo by author

2/21/20

To build the sides of the basket, I began adding bundles on top of the outer most row/coil of the base. I began using interlocking stitches (wrapping sinew around the bundle, threading it through the sinew to the bundle below, out and repeat). This created a pleasant diagonal pattern, as well as an easy way to add new bundles of needles as I built the sides.

Interlocking stitch

Photo by author

2/1/20

As I approached the desired height of my basket, I added smaller diameter bunches (3 clusters) of needles to form the final ring/coil. I wanted the top to lean in slightly, so I pulled the bunches tighter and in toward the center of the basket. I then stitched the sinew over itself on the inside of the basket and tied a small knot. Ta-Da! The basket was complete!

Finished Basket Photo by author 2/21/20

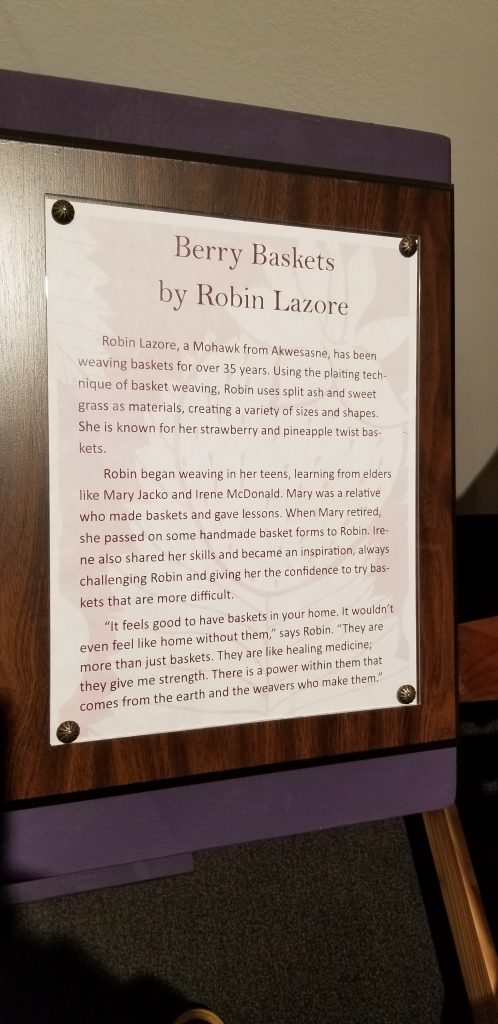

I would also like to include images of two beautiful baskets that I saw while visiting the Onöhsagwë:de’ Cultural Center, Seneca-Iroquois National Museum & Seneca Nation Archives. I was stunned by the colors, patterns, artistry, and skill that went into these and I hope they impress you as much as they did me.

Berry Basket by Robin Lazore

Photo by Author

2/20/20

Berry Basket Plack

Photo by author

2/20/20

Community Basket

Photo by author

2/20/20

Community Basket Plack

Photo by author

2/20/20

References:

Burns, R. M., and Barbara H. H. (1990). Silvics of North America: Volume 1. Conifers. Agriculture Handbook

654. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Washington, DC.

Geniusz, M. (2015). Plants Have So Much To Give Us, All We Have To Do Is Ask. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, MN.

Lee et al. (2015). Hippocampal Memory Enhancing Activity of Pine Needle Extract Against Scopolamine-Induced Amnesia in a Mouse Model. Scientific Reports, 5:9651. DOI: 10.1038

Patterson, N. (2013). Great Tree of Peace: The White Pine. Retrieved from https://adk-nfc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/White-Pine-Tree-of-Peace-Indigenous-People-NY.pdf.

PFAF (n.d.). Pinus Strobus – L. Retrieved from https://pfaf.org/user/Plant.aspx?LatinName=Pinus+strobus.

Sibley, D. A. (2009). The Sibley Guide to Trees. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, USA.

Singh, S. P., Inderjit, Singh, J. S., Majumdar, S., Moyano, J., Nuñez, M. A., & Richardson, D. M. (2018). Insights On The Persistence Of Pines (Pinus Species) In The Late Cretaceous And Their Increasing Dominance In The Anthropocene. Ecology and evolution, 8(20), 10345—10359. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.4499

Tod, O. G., & Breen Del Deo, J. (2017). Earth Basketry: Weaving Containers With Nature’s Materials. Schiffer Publishing Ltd., Atglen, PA.

Uprety, Y., Asselin, H., & Bergeron, Y. (2013). Cultural importance of white pine (Pinus Strobus l.) to the Kitcisakik Algonquin community of Western Quebec, Canada. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 43:544-551. DOI: 10.1139/cjfr-2012-0514

Posted: February 2020, updated: May 2020