Description

Populus balsamifera Linnaeus is a deciduous tree in the Salicaceae (willow) family. Populus comes from Latin “of the people” which shows how relevant and widely used the genus is. Balsamifera comes from Latin via the Hebrew word for perfume. The genus of Populus L. contains a number of related cottonwood species. There are two relevant species found in Alaska, Populus balsamifera L. ssp. balsamifera (balsam poplar) and Populus balsamifera L. ssp. trichocarpa (black cottonwood). Balsam poplar is the northernmost hardwood in North America. It occupies the northern range of the species and black cottonwood is found west of the Rocky Mountains as far south as northern Mexico. The species readily hybridizes with other cottonwoods of the genus especially in the margins of its range with hybrid trees bearing characteristics of both parent trees. It’s been found to hybridize with an introduced European species (P. nigra) around Montreal (efloras.org).

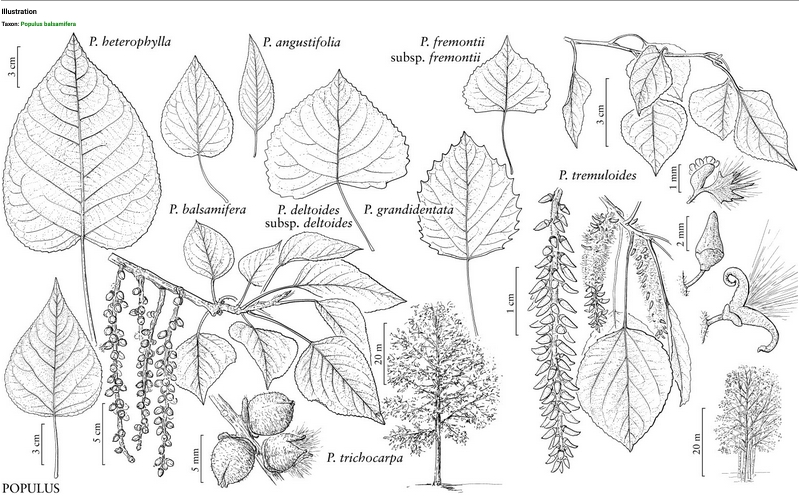

Image of Populus sp. from http://efloras.org/object_page.aspx?object_id=114029&flora_id=1.

According to the USDA Plants database, balsam poplar has dark gray furrowed bark. The trunk is straight and tall with the height at 20 years of age to be about 35 feet and about 80 feet as a mature tree. The dark green ovate leaves have a silvery underside. The trees are dioecious with separate plants having either male or female flowers. The catkins appear before leaves emerge in April or May. The female catkins grow to 2 to 6 inches long. When mature, the female catkins contain capsules that burst open to release cottony seeds. It is pollinated by wind and the seeds germinate readily.

Balsam poplar has a high fire tolerance, needs 75 frost free days, tolerates a pH in the range of 4.5 to 7, needs 6 to 70 inches of precipitation each year, and can live through temperatures as low as -79 degrees Fahrenheit. Balsam poplar is quick growing and abundant in logged and burned-over areas. The Plants for a Future database describes Populus balsamifera as a pioneer species that emerges in abandoned fields, flood plains, old burns and logged areas. It is shade intolerant and also intolerant of root and branch competition meaning that at a certain point, other species will overtake it.

In addition to all this descriptive data, watch this heartening Youtube video about the cottonwood (The Orchard Enterprise, 2013). There is a dark red star shape that appears when you cut a cross-section of a small cottonwood branch or twig. This Dakotah story as told by Mary Louise Defender Wilson describes a star who was drawn to a village because of a beautiful sound. I won’t give away the ending, so listen at https://youtu.be/WPVvIKEi_d8 to find out how the star got inside the cottonwood tree.

Distribution

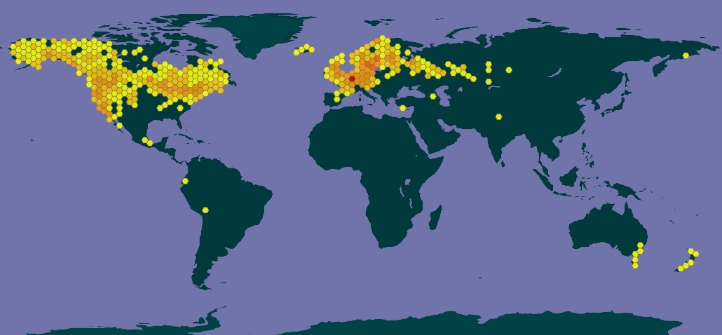

The GBIF website was a new resource to me and I retrieved these colorful maps from it. Last spring when I was gathering the material for this project, I wasn’t aware of the two species in Fairbanks, so I’m not sure which I used for the project. I will definitely pay attention this spring and try to identify them. As an aside, my father is very good at identifying trees (probably from a mix of childhood experience in the woods and also he is a gifted mechanic with attention to detail and good memory) and I hope to get better at it.

Populus balsamifera L., Retrieved on 4 Dec 2020 from https://www.gbif.org/species/3040184

Populus balsamifera subsp. trichocarpa (Torr. & A.Gray) Brayshaw, Retrieved on 4 Dec 2020 at https://www.gbif.org/species/3806052.

Alaskan distribution from Anore Jones’ Plants That We Eat (2010, p. 175)

Uses

The Native American Ethnobotany Database shows 531 uses for the query of “Populus” and 173 uses for “Populus balsamifera”. All parts of the tree are used by Indigenous people, from the resinous buds to the inner bark to the fluffy seeds. Uses include teas, salves, boxes, tools, fuel, paint, fiber, forage and many others (Native American Ethnobotany DB).

According to Anore Jones in Plants that We Eat (2010), the wood is for building and for carving. The buds can be soaked in oil, grease or alcohol to make a tincture to use in salves. The salves are good for “all-purpose healing medicine” for such ailments as burns, cuts, diaper rash, toothache, sore throat, and nasal congestion. The inner bark (cambium) is a good laxative. (p. 175).

Beverly Gray writes in The Boreal Herbal (2011) that, in addition to the above-mentioned salve, an inner bark tincture contains salicin and is a remedy for fever, rheumatism, arthritis, and diarrhea. The catkins are high in vitamin C and can be eaten raw or added to stews. (p. 256).

Scientific journal articles show recent research on antibacterial, antiviral and cytotoxic (toxic to cells, used in anti-cancer research) properties of the resin of Populus balsamifera. Of the articles I read, the one I shared with the class, “New Antibacterial Dihydrochaclone Derivatives from Buds of Populus balsamifera” was written in the simplest language for a non-chemist and also was the shortest. The authors isolated three new compounds called “balsacones” and tested them along with 7 others found in balsam poplar resin against Staphylococcus aureus, E. coli, and normal skin fibloblast cells (Lavoie et al., 2013, p. 1631). They found all compounds to be inactive against staph and only the three new balsacones to be effective against E. coli. They found the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) that was effective at reducing the amount of E. coli to be low enough as to be a reasonable dose (p. 1633). Interestingly they did not include the time of year that the buds were collected.

Other research has been conducted on propolis, the sticky product made by bees from resin, most often but not always from the Populus genus. Propolis is used by bees to seal up any gaps or cracks in the hive. Propolis is chemically similar to this resin. Broadhurst and Duke (1998) report that used in conjunction with the antibiotics penicillin and tetracycline, the drugs’ effectiveness is increased 10 to 100 times. Cafeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) is one antioxidant in propolis that is especially effective at reducing cell growth when tested against human cancer cells. (Broadurst & Duke 1998)

“Balm of Gilead”

The resin of the balsam poplar buds is commonly called balm of Gilead It is extremely fragrant. This signature scent, once smelled, is not easily forgotten. But why, I asked myself, does this tree which is indigenous to North America, produce a medicine with a name rooted in Judeo-Christian traditions?

Balm of Gilead appears in the Old Testament of the Bible. The word balm in English can refer to healing in general, both spiritual and physical. The general consensus is that the Judean Balsam tree (Commiphora gileadensis) produced the balm mentioned in the Bible. This medicine is mentioned by Pliny (Greek) as a cure-all and in the Middle Ages it was the most valuable agricultural product coming out of the Middle East selling for twice the price of gold (Ben-Yehoshua et al, 2012, pp.47-64).

The salve made from North American cottonwood trees is obviously not the same as this product from the Middle East. It is easy to imagine how European settlers equated the sweet-smelling and powerful salve to this biblical balm of Gilead.

My Project

I have titled my project “Cottonwood Oil” to avoid using the name “balm of Gilead”. This fragrant medicine needs a non-Euro- and Judeo-Christian-centric name. Unfortunately, I couldn’t find much information on alternative names and am thus open to suggestions. I struggled to find Native American names for balsam poplar. What I found was scattered across a few on different regional websites (Maine and Washington). I did not find any names specifically for the resin or medicine made from it. Beverly Gray calls hers “Boreal Balm” which she sells as her Aroma Borealis shop in Whitehouse, YT (Gray, 2011, p. 314).

Suzanne Tabert of the Cedar Mountain Herb School suggests in her blog post Cottonwood and Willow: Nature’s Pain Relievers gathering the buds from fallen branches after a windstorm in the fall and winter months. I went out in early May on a sunny weekend day to search for chaga. In doing so, I noticed the tall stands of cottonwood or balsam poplar along the upper Chena River and their fragrant sticky buds and decided to gather a handful for this project. I gathered them straight off the trees with branches I could reach, meaning the smallest ones, and the buds were starting to open and the leaves were unfolding. This is not the harvesting technique I would use now.

Cottonwood buds. Photo by author on 5/3/2020, Fairbanks, AK

Then I steeped the buds in a cup of olive oil because it’s what I had on hand. I was loosely following Anore Jones’ instructions. I left the jar in a dark spot on a shelf and tried to remember to shake it occasionally.

Cottonwood buds in olive oil. Photo by author on 5/6/2020, Fairbanks, AK.

In September, I asked a beekeeper friend for a couple tablespoons of beeswax, and she brought a yogurt container full of honeycomb wax. I tried to follow the directions in The Boreal Herbal (Gray, 2011, p. 312) First I slowly melted down the wax. It was full of dark pieces that didn’t melt well, and in the end, I left some of this in because I liked the rustic texture. While the wax was melting, I strained the buds through a cloth, squeezing as much of the oil as I could. This got oil all over my hands, the cloth, the jar, and the counter. I tried to save as much as I could. Surprisingly, the container of beeswax yielded about a tablespoon of wax which turned out to be perfect for the amount of oil I had. Beverly Gray’s Basic Salve Recipe on p. 312 calls for Vitamin E and benzoin oil as a preservative and fixative, but I skipped that part. I decided that the antibacterial properties of both the resin and the beeswax would be enough for me. I wasn’t sure what to do with the leftover buds. After filling the jars and letting them cool, I used the heat gun to melt the top layer of hardened salve and added a bud to each jar as decoration before sending the rest to the compost pile. My house smelled amazing, my hands felt moisturized, and I gave a jar to my beekeeper friend.

Melting the beeswax. Photo by author 9/28/2020, Fairbanks, AK.

Straining the oil. Photo by author 9/28/2020, Fairbanks, AK.

Partially melted beeswax. Photo by author 9/28/2020, Fairbanks, AK.

Testing the consistency and filling containers. Photo by author 9/28/2020, Fairbanks, AK.

Three full 2oz. containers and the leftovers. Photo by author 9/28/2020, Fairbanks, AK.

Conclusion

I learned so much more than I expected from this project. First, thus far my plant projects have been very short-term. I started the ethnobotany program while working for a hydroponic farm where all the herbs we grew were available all the time. I have happily foraged and consumed plants and fungi wherever I happen to be but the extent of my long-term projects have been freezing or drying herbs and canning berries. My excuse to avoid long-term projects was always that I was traveling, moving, or focused on work. For this project, I gathered material and left it for 4 months before making the medicine. I feel more centered and ready to observe the cycles of the ecosystem around me. I will take the winter windstorm as a cue to walk outdoors and visit the cottonwood stands to gather a few buds from downfall. I’ll steep the buds in oil or honey for some skin and respiratory medicine, which I need more in the winter anyway, and share the gifts with anyone who needs it.

Suzanne Tabert writes that “the tips of the branches look like gnarled witches fingers” (Tabert). She adds that the salicin is found in the first couple inches of wood beyond the buds, those gnarled finger bones. When I gathered the buds in April, I joked about the creepy finger shapes with my friend. I didn’t look past this to observe the medicine inside the plant was good for arthritis and soreness for witches and the rest of us.

Another observation I had recently which both highlighted my ignorance and opened my eyes was how the bees use the resin. Beekeepers call it “bee glue” and the bees use it to patch cracks and gaps in their hive to seal it off from intruding pests and the elements. Indigenous people use the resin to waterproof things and patch holes. I have so much to learn from bees. Robin Wall Kimmerer writes of the three strands of plant knowledge in her beautiful book Braiding Sweetgrass. This quote is from a 2017 interview by author Margaret Roach of Kimmerer and the emphasis is my own:

One of those strands is Indigenous knowledge and traditional environmental thinking about plants from the Native perspective. Another one of the strands of that braid of stories is scientific knowledge about plants, and then there’s that third strand that makes up the beautiful braid. The way that I think of that third strand is the knowledge that the plants themselves hold, that not what we can learn about plants, but what we can learn from plants. So, the book is this braid of stories that use those three different ways of knowing to reawaken our relationship with plants and to fully engage with all of our human ways of knowing the gifts that plants hold for us. (Roach, 2017)

What could I learn from sitting next to a balsam poplar and watching the coming and going of other plants, insects and animals over time?

References

Ben-Yehoshua, S., Borowitz, C., & Hanus, L.O. (2012). Frankincense, myrrh and balm of Gilead: ancient spices of southern Arabia and Judea. In J. Janick (Ed.), Horticultural Reviews Volume 39 (pp. 1-66). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118100592.ch1.

Broadhurst, C.L. & Duke, J.A. (1998 March/April). Propolis: an age-old medicine. Mother Earth Living. https://www.motherearthliving.com/health-and-wellness/inside-plants-8.

Flora of North America. (n.d.) Retrieved on 26 Oct 2020 from http://efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=1&taxon_id=242430290.

Gray, Beverly. (2011). The boreal herbal: Wild food and medicine plants of the North. Aroma Borealis Press.

Jones, Anore. (2010). Plants that we eat: nauriat niġiñaqtuat (2nd ed.). University of Alaska Press.

Lavoie, S., Legault, J., Simard, F., Chiasson, E., & Pichette, A. (2013). New antibacterial dihydrochalcone derivatives from buds of Populus balsamifera. Elsevier Tetrahedron Letters. 54 (13), 1631-1633. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tetlet.2012.12.012.

Native American Ethnobotany DB. (n.d.) Retrieved 26 Oct 2020 from http://naeb.brit.org/.

Populus balsamifera L. (n.d). Global Biodiversity Information Facility. Retrieved on 4 Dec 2020 from https://www.gbif.org/species/3040184.

Populus balsamifera L. (n.d.) Plants for a future. Retrieved 26 Oct 2020 from https://pfaf.org/user/Plant.aspx?LatinName=Populus+balsamifera.

Populus balsamifera L. (n.d.) USDA Plants Database. Retrieved 26 Oct 2020 from https://plants.sc.egov.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=POBA2.

Populus balsamifera subsp. trichocarpa (Torr. & A.Gray) Brayshaw. (n.d.). Global Biodiversity Information Facility. Retrieved on 4 Dec 2020 at https://www.gbif.org/species/3806052.

Roach, M. (2017, December 25). Lessons in the plants: “Braiding Sweetgrass”, with Robin Wall Kimmerer. A Way to Garden. https://awaytogarden.com/braiding-sweetgrass-robin-wall-kimmerer/.

Tabert, S. Cottonwood and willow: nature’s pain relievers. (n.d.). Cedar Mountain Herb School. Retrieved 26 Oct 2020 at https://cedarmountainherbs.com/cottonwood-and-willow-natures-pain-relievers.

The Orchard Enterprises. (2013, October 27) The star in the cottonwood tree – Mary Louise Defender Wilson. [Video]. Youtube. https://youtu.be/WPVvIKEi_d8.

Posted on December 7, 2020

- Author: Sundance Visser