Botanical Information

Species: Pandanus tectorius Parkinson ex Du Roi (Pandanaceae)

Common names: thatch screwpine, hala tree, pandanus

Hawaiian name: pu hala (Carr, 2002)

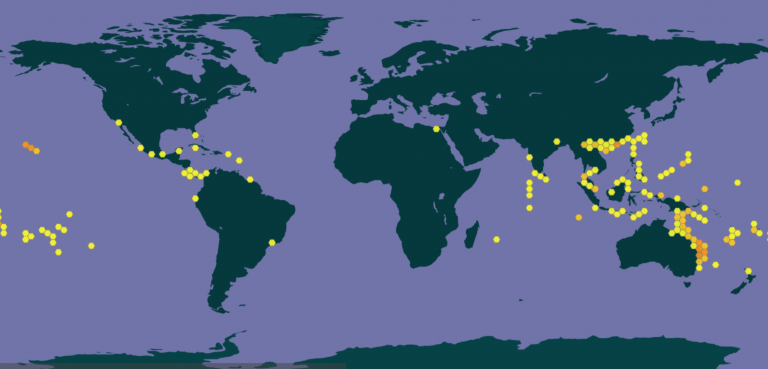

Pandanus tectorius is a dioecious member of the screwpine family of monocotyledons. It is native to the Pacific Islands, Australia, and Malesia where it prefers coastal areas such as mangrove edges as well as beaches (Gallaher et. al., 2015, p30). While cultivation introduced the tree to some areas, research shows that it was on the Hawaiian Islands before human settlement and is located on all of them except Kaho’olawe (Carr, 2002). Pandanus tectorius is the most widespread species in the screwpine family and research shows it originated in Queensland Australia and dispersed throughout its range by hydrochory (Gallaher et. al., 2015, p31). The range for this species extends across the equatorial and some temperate regions of the globe as seen in the map below.

The tree can grow up to 45 ft in height, has a slim ringed and spiny trunk, and is rooted in place firmly with prop roots that can originate from branches but most commonly from the trunk (Kinsley, 2021). The male flowers form racemes in groups of three that are subtended by large bracts(Kinsley, 2021) These flowers only last one day. Female flowers display a large inflorescence of off white flowers that develop into a multiple fruit containing up to 200 carpels, each with an average number of 2 seeds (these carpels are called phalanges) (Carr, 2021). The phalanges are buoyant and salt tolerant and can travel over long periods of time by ocean current (Carr, 2021). Hala leaves are spirally arranged on the ends of branches. Leaves can reach 5 ft in length and 3 in width (Carr, 2021). Leaves have thorny margins and midribs.

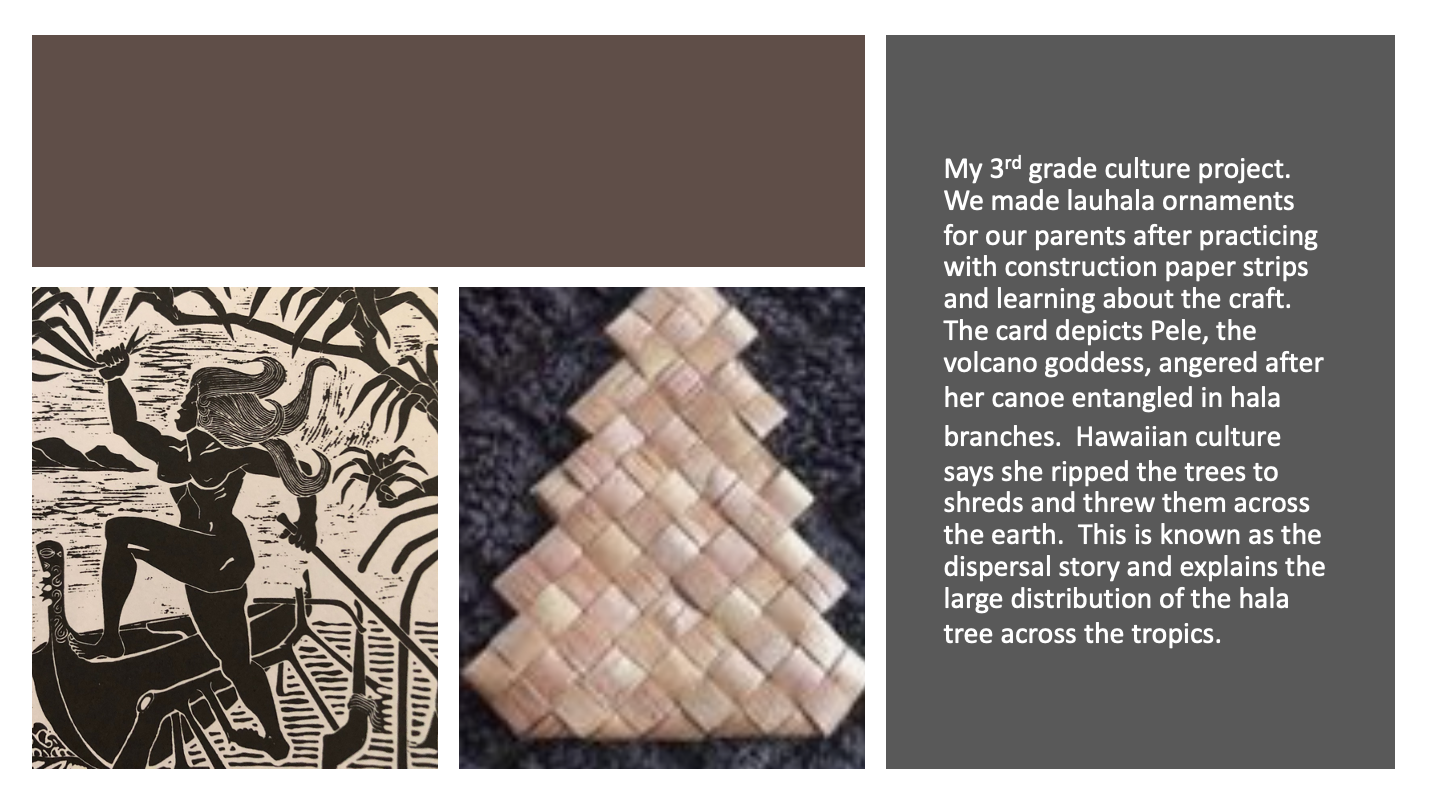

Traditional uses of the hala tree

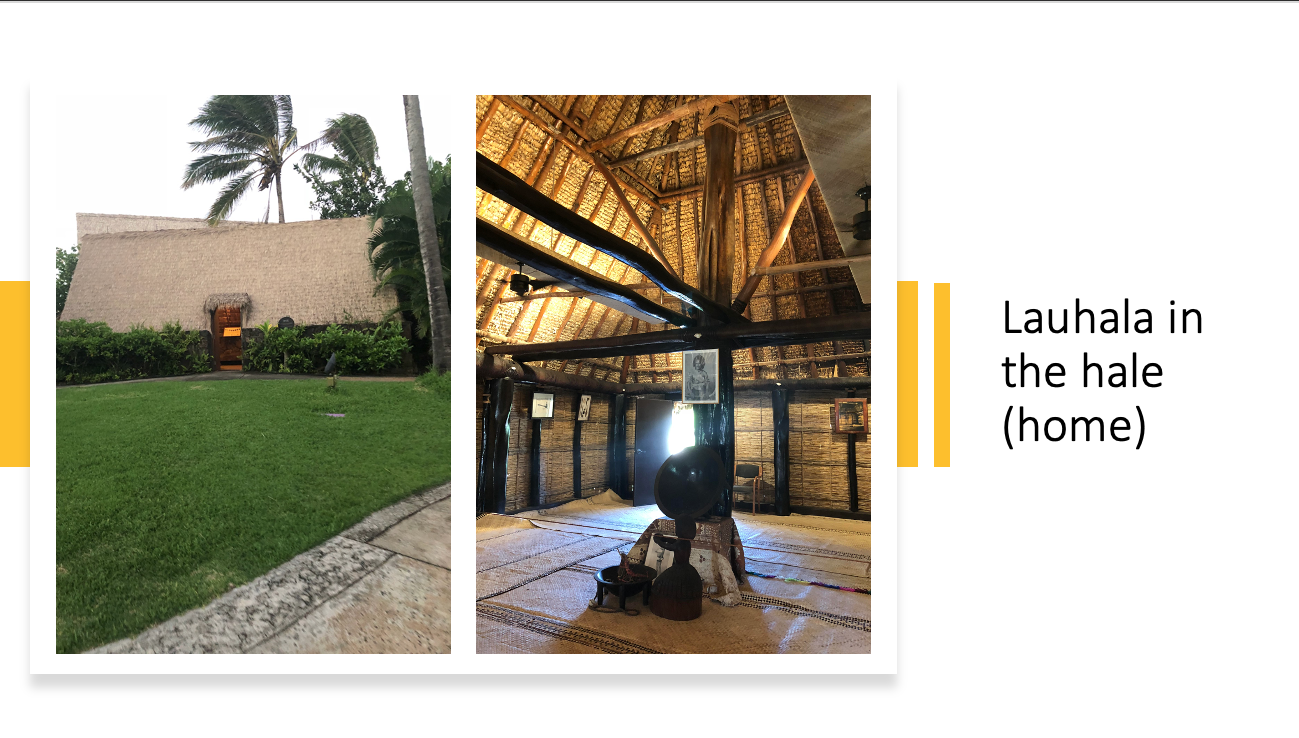

Lauhala weaving products were used for the home, transportation, as fans, and garments. Hala leaves were often chosen for thatching the roofs of homes and in the form of large mats, comprised the flooring. Mats were also used as bedding material.

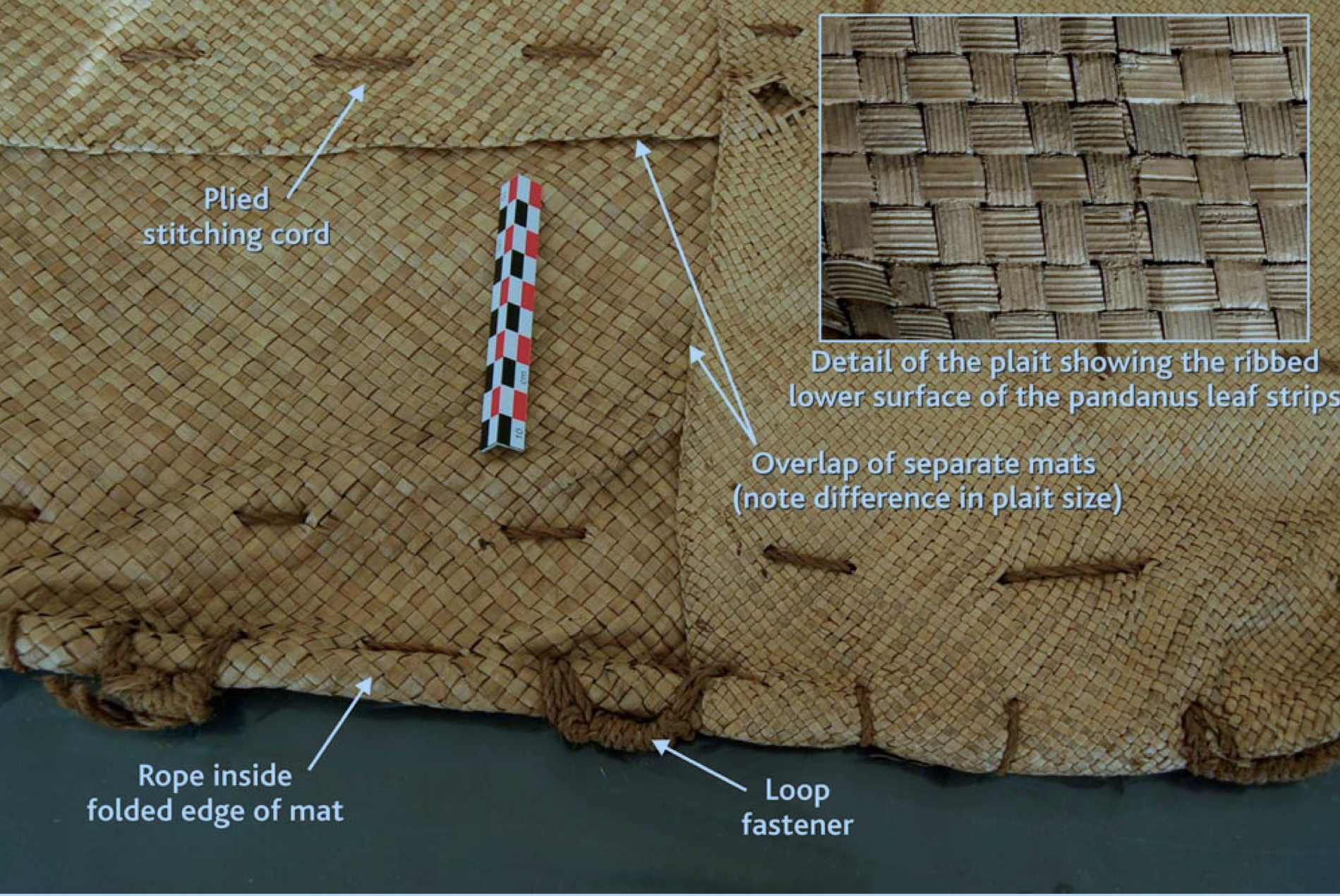

Specially woven sails of interlocking mats were used as sails by early Hawaiians as well as other island cultures. The detailed picture below is of a Tahitian sail from Captain Cook’s collection (He Make’e Wa’a, 2015).

Lauhala weaving was used for other daily use items such as trays, baskets, shade hats, grass skirts, loincloths, ceremonial bracelets and anklets as well as cordage. In colonial times the tight weave of lauhala baskets were utilized to hold coarse grain sugar by plantation workers (Bird, 1982, p128).

Other parts of the tree were readily used by ancient islanders. The fruit can be eaten (although the species native to Hawaii has an acrid taste) and bracts from male flowers are used for weaving and for leis. Fragrant flower parts were used to scent stuff pillows and pollen from the male tree was also used as a prevention of chafing beneath loincloths (Bird, 1982, p5). Soft fibers of the fruit was used to make brushes used to paint bark cloth for clothing, the trunks of male trees were once used for house posts and to carve bowls, and aerial root fibers were used for cordage (Bird, 1982, p9). Rich in vitamin B, the starchy aerial root tips was cooked by early Hawaiians while leaf buds were used medicinally (Bird, 1982, p9).

Hala leaf harvest and preparation

Leaves are mostly gathered from the ground around the base of the tree. You can use leaves from the tree but this is not a common practice. If you take live leaves you have to allow them to dry before usage. Leaves below the tree are usually already dried and it is more sustainable to use these. Once you have your leaves you would cut the base off as this part is too stiff to work with and then you remove the thorns from the edges. If the midrib is thick you should trim it. Leaves should be wiped down with a damp cloth. The leaves need to be rolled around a bamboo stick with a slit in one end (PVC piping works too). Early Hawaiians used their hands for this job. The leaves are rolled in both directions over and over to make them more pliable and flatten them out. You can also use a pasta press for this job and there is a tool made for this purpose as well. Once the leaves are flat you roll them into a wheel that is called a Kuka’a.

The leaves I used for my project were prepared by my friend Jeanette’s neighbor, Leilani Heito. She gathered them from Jeanette’s hala tree. Leilani is a lauhala instructor at the Hale Kula Senior Center and at local high schools on the windward side of Oahu. She learned her art later in life and told me that she grew up in a time when native Hawaiians were not taught their language and culture. She says that lauhala has been liberating in that it allowed her to be Hawaiian and her whole true self. She enjoys passing the tradition on to the youth and introducing it to her own generation as a way of healing. Leilani explained to me that you can not weave hala leaves in a bad mood and I had to keep that in mind when I became frustrated with my basket project.

Lauhala Basketry

Materials:

- Twelve 1/2 inch lauhala strips about 55 inches in length. You can change the length and width for different sized baskets.

- Thread to hold strips in place.

- Clothespins to keep folds in place

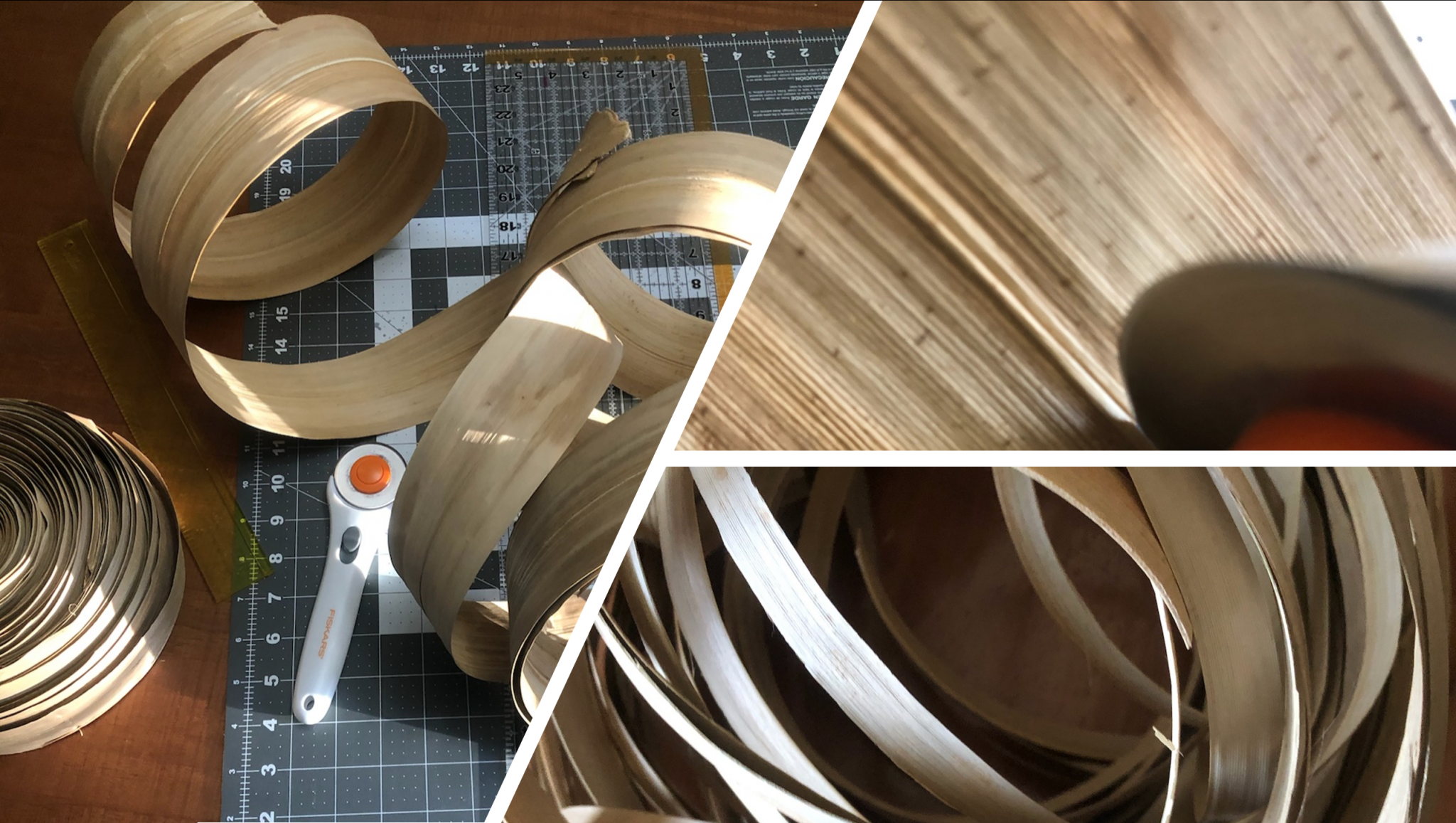

To begin, I had to cut the leaves into strips. Hawaiian weavers have two general tools to do the stripping that cut one leaf into equal sized strips with one movement. Early weavers used thorns held between fingers of a fisted hand.

I used quilting rulers and a rotary cutter to cut strips since I don’t have the correct equipment. It was difficult to get uniform sized strips and after a few attempts, I discovered that cutting from the midrib of the leaf worked best since nature provided this as a straight line.

When I interviewed Leilani, she said that lauhala is not just about weaving a basket or mat, it is about weaving relationships. Later she sent this picture she took of a repair retreat she attended. The aim of the retreat was to repair a historical mat for the Iolani Palace in Honolulu. These large mats are called moena and weaving them is a communal event and Leilani said that “together, we learn by doing”.

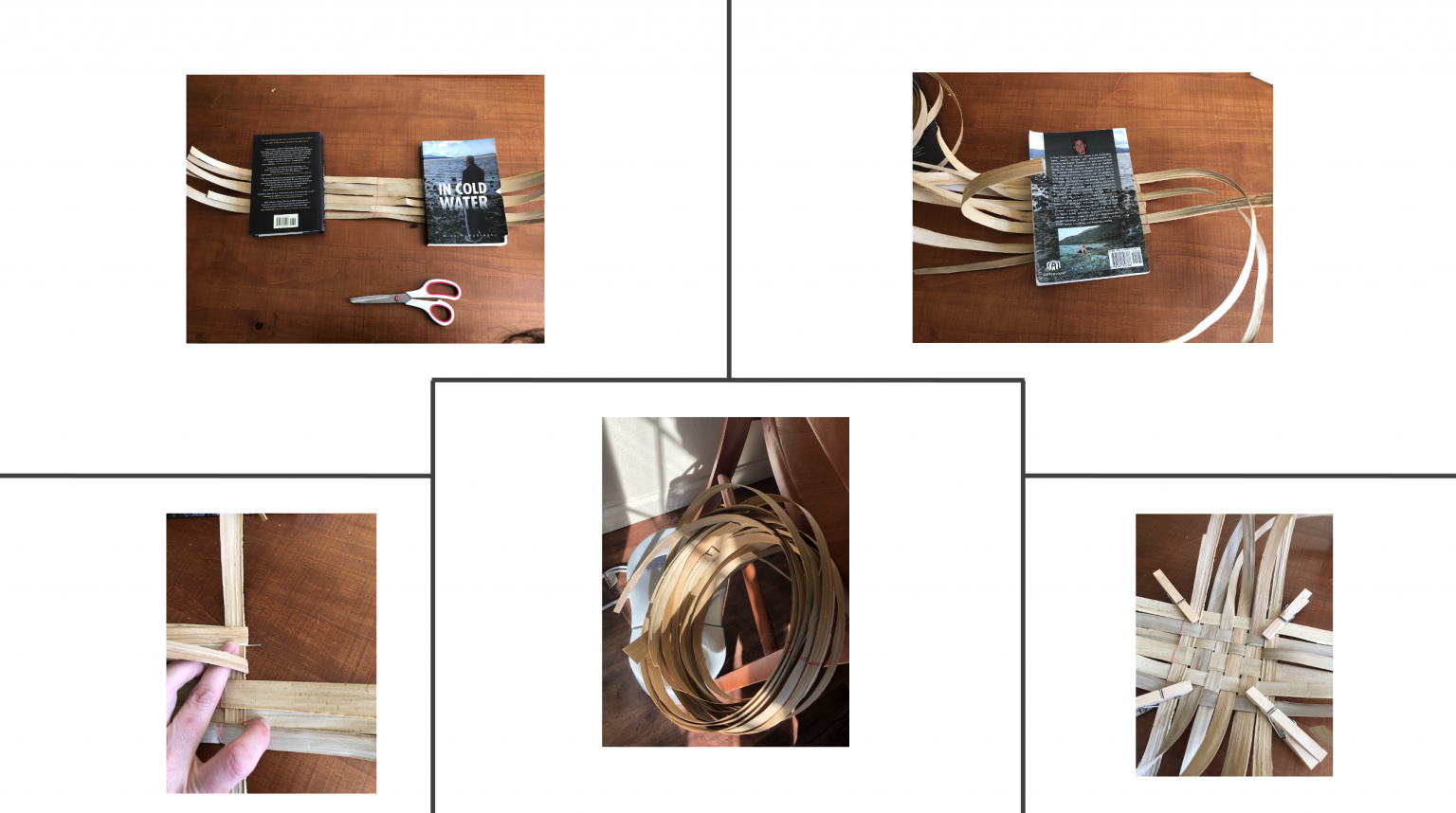

Weaving the basket called for starting with an even number of strips (half of the total) lined up and tied together with thread. Next, I folded back every other strip. This is when I realized that my leaves were too dry from being stored in a heated house for a few months. I set them over a humidifier to soften them. Next I put one of the extra strips perpendicularly across the strips that were not bent and then began weaving the strips. All of the extra strips were added and woven into the project.

Lauhala techniques bring the weave at a diagonal when you make the corners but my leaves were too dry to bend in the proper direction so I did a simple weave to complete my basket.

Below is a picture of a vintage lauhala basket with the diagonal weave.

Video of project: https://youtu.be/STEcySD9Ze8

Resources:

Bird, A., Goldberry, S., Bird, J.P.K. (1982) The craft of Hawaiian lauhala weaving. The University of Hawaii Press

Carr, G. (2002, July 16). Pandanus tectorius. Retrieved April 14, 2021, from https://www.ctahr.hawaii.edu/hawnprop/plants/pan-tect.htm

Gallaher, T., Callmander, M. W., Buerki, S., & Keeley, S. C. (2015). A long distance dispersal hypothesis for the Pandanaceae and the origins of the Pandanus tectorius complex. Molecular Phylogenetics & Evolution, 83, 20–32.

Hiquily, T., Newell, J., Pullan, M., Rode, N., Bernucci, A. (2009) Sailing through history: conserving and researching a rare Tahitian canoe sail. The Technical Research Bulletin of the British Museum. Vol.3.

Kinsley, B. (2021). Pandanus tectorius – Hala. Retrieved April 14, 2021, from https://wildlifeofhawaii.com/flowers/1091/pandanus-tectorius-hala/

Cultural Context (2015). He Make’e Wa’a. Retrieved April 17, 2021 from https://www.hemakeewaa.org/cultural-context

Unique Construction (2015). He Make’e Wa’a. Retrieved April 17, 2021 from http://www. hemakeewaa.org/Unique-contruction

Posted: April 2021