“We ask: do we really need bannock, or do we just desire bannock? Which leads to asking one of our Elders, Therese, about traditional flours, which leads to an afternoon collecting cat tails to make flour” (Ballantyne, 2014, pg.17).

Bannock

With winter upon us, I have been looking for an excuse to make and eat bannock, comfort food for these long cold days. I was gifted a little jar of wild berry jam (from ethnobotanist Nancy Turner!) last year and thought it would be the perfect accompaniment. Growing up, I always associated bannock with the Indigenous groups of Canada. I had never given much thought to the origins of bannock until recently. Clearly this white flour goodness hadn’t been consumed in Canada for very long, so I wanted to know, where did it come from and why do I think of it the way I do? It has been documented (very little!) that some indigenous groups made a “bannock’ from ground bulbs and other plants before the introduction of white flour by settlers. Through this paper, I tried to find out more information about the origins of bannock in Canada, the importance of bannock to Indigenous peoples, and also of this pre-contact bannock made of ground plants, the ethnobotany of bannock.

Bannock. An Introduction

Bannock, a round of mostly flour, baking powder, water and some sort of fat, has been a part of Indigenous peoples’ diets since the 18th century. It is believed that bannock, derived from the Gaelic word bannach, was introduced here by the Scottish fur traders. Most Indigenous groups in Canada have some version of bannock. The Inuit call it palauga, the Mi’kmaq, luskinikn, and the Ojibwa, ba’wezhiganag (Colombo, 2006).

Carbohydrate-rich and simple to make, bannock soon became a staple for Indigenous people across Canada. It goes without saying, however, that part of this was also due to colonization and the removal of Indigenous peoples from their land and traditional food sources (Colombo, 2006). Rations of flour, lard, sugar and eggs became the norm and bannock became a deep-rooted part of Indigenous culture. This can be a tricky subject, and I won’t delve into this very much, but what I have found during my research is that cooking, sharing, and eating bannock can be an empowering experience for all.

“Bannock can go far and can feed many, but it has to be done with love,’ she said, standing in the newly renovated cafe. “Bannock was what we had to eat, but now I want to pay homage to the dignity of our women who have learned to turn a negative into a positive’ (Gilpin, 2017).

The Ethnobotany of Bannock

Folklorist and food writer Lucy Long writes that “prior to the loss of traditional foods, most indigenous people had some version of a breadlike staple, often called bannock, made of ground bread root, acorn, bean, or corn flour mixed with water and fried in animal fat or cooked on hot, flat stones’ (2015, pg. 446).

Ethnobotanist Nancy Turner reiterates this in an article about bannock, by suggesting “unleavened breads made from the starch/flour of bracken rhizomes were probably “cooked/baked on rocks over the fire, in sand, or in cooking pits or earth ovens’ (Bell, 2018). Another example of a pre-colonial version of bannock was camas bulbs that were baked, dried and chopped or flattened, then shaped into cakes or loaves (Colombo, 2016).

Some Interior First Nations cooked black tree lichen, Bryoria fremontii Tuck., and dried them into cakes, and, similar to bannock, they were eaten on long journeys as a sustainer (Turner, 1997, pg. 35).

Post-colonial bannock, the white flour variety, is widely intertwined with ethnobotany.

The Nlaka’pamux of British Columbia added bitterroot, Lewisia rediviva, to their bannock. It was considered a delicacy, almost a desert, often alongside Saskatoon berries, Amelanchier alnifoli (Bandringa, 1999, pg. 22).

Black mountain huckleberries, or mountain bilberries, Vaccinium membranaceum, were added to bannock by the Chipewyan people of northern Saskatchewan (Kuhnlein & Turner, 1991, pg. 118).

The Woods Cree, also of Saskatchewan, made birch sap into a syrup, thickening it with flour, and ate in on bannock (Kuhnlein & Turner, 1991, pg. 90).

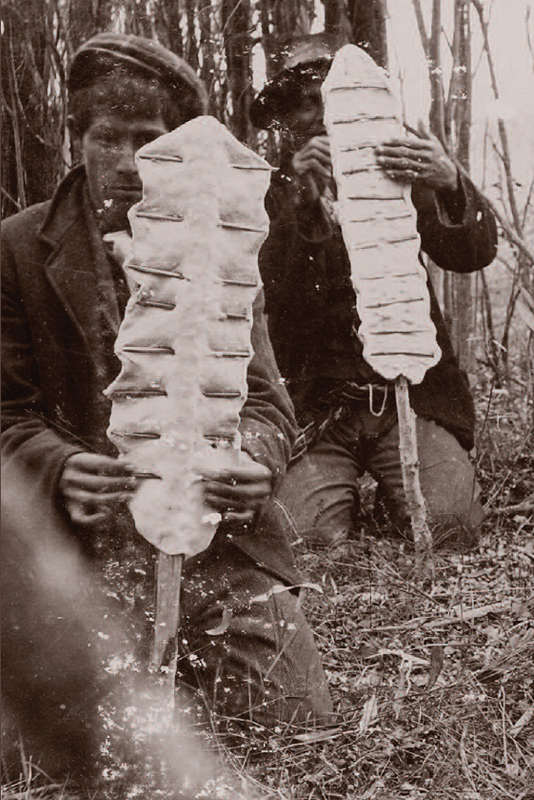

Some Indigenous groups wrapped the dough around a green, hardwood stick and toasted it over an open fire (Bannock Awareness, 2001, pg. 16).

Cultural Value of Bannock

In researching the history of bannock in Canada, I stumbled across a book called Bannockology. A Community Collaboration of Stories, Art, Essays, Recipes and Poems about Bannock. I contacted the publisher to obtain a copy, and they generously gifted me one. It was compiled by Peter Morin, the organizer of the “People’s Bannock.’ This event’s intention was to bring awareness to mineral extraction in Northern B.C. by attempting to make the world’s largest bannock (at 50 feet long!) – “Bannockology is an anthology of anecdotes, recipes, poetry and insights about bannock, the ubiquitous bread that is a part of every First Nations social event, private or public.’

With over 30 entries about bannock, Bannockology helps define how important this staple is to Indigenous peoples across Canada:

Bannock is sort of like our “Jesus-bread’, it is the “flesh’ of our culture.

Bannock has two distinct functions amongst us Indian peoples: first function — It fills our bellies, second function — it fills our souls’ ~ Nanette Jackson (Morin, 2009, pg. 25).

I found many other quotes in various publications that reflect how culturally important bannock is to virtually every Indigenous group in Canada:

“Yet, many Elders tell me that they get sick on ‘Whiteman’s foods,’ and that they are much happier eating wind-dried salmon and bannock every day. It is also the case that salmon, bannock, berries, and other ‘Indian foods’ are locally prepared by people whom one knows, and under known circumstances. Such food, ‘prepared with love,’ provides far more than physical nourishment’ (Palmer, 2005, pg. 76).

For the Inuit, this staple was a “legacy of the nineteenth century contact with whalers’ (Billson & Mancini, 2007, pg. 42). Made with seal oil so it would not freeze, bannock became a traditional food of the Inuit. When researching their book “Inuit Women, Their Powerful Spirit in a Century of Change, authors Billson and Mancini did some more informal “natural gathering’ interviews with Inuit women over tea and bannock (xiv). This simple offering (of bannock) shows the importance of bannock in the Inuit culture.

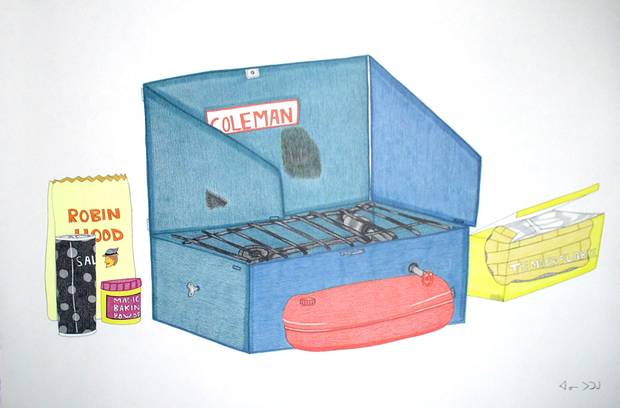

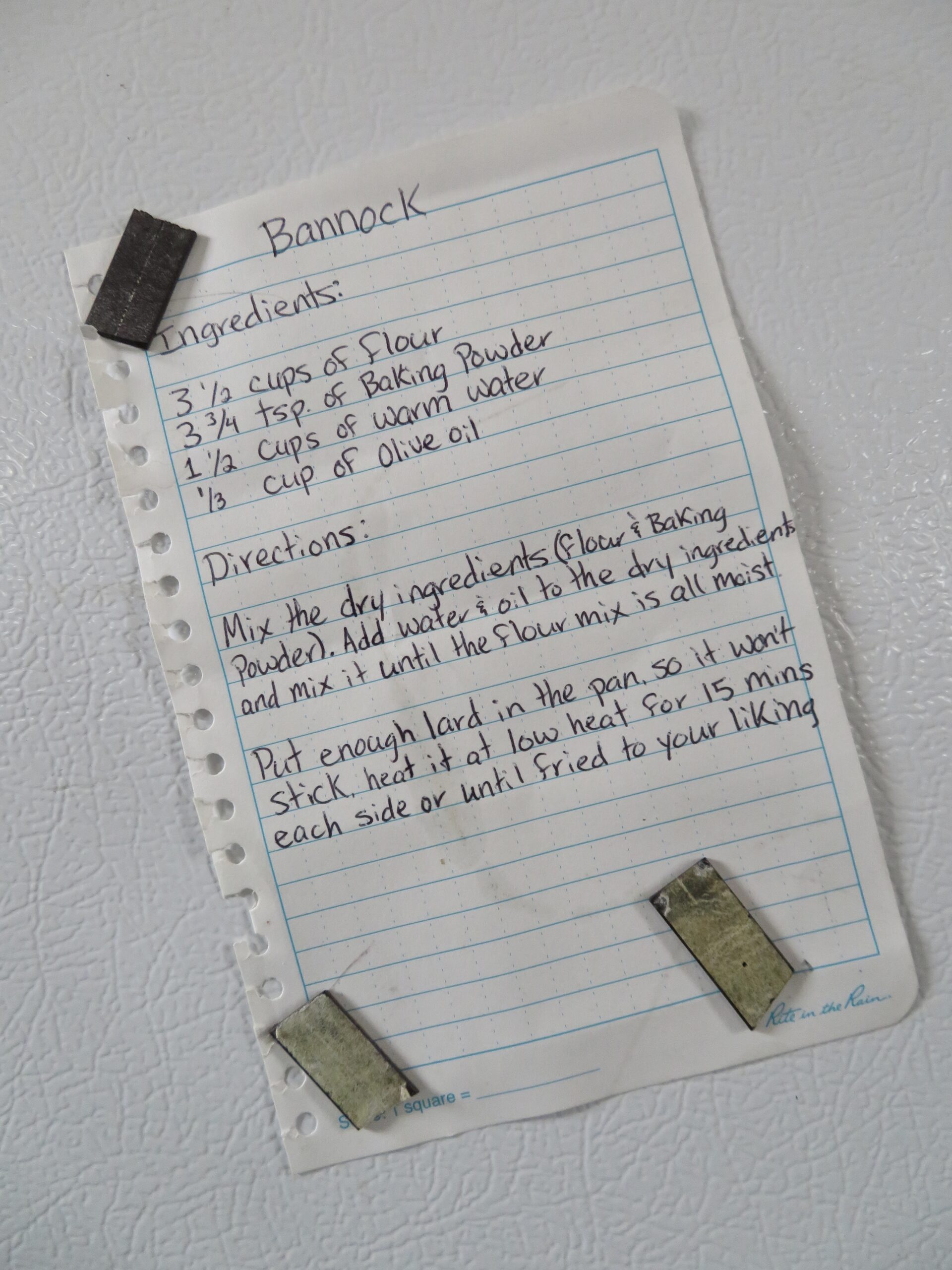

When I was in the Canadian Arctic last summer, I had the pleasure on numerous occasions to eat bannock made by an Inuk I was working with. There was even a recipe for bannock on the camp fridge which was at 81.4 degrees north! Inuit bannock, or palauga, is rich part of the Inuit heritage.

Bannock plays a vital role in the lives of Indigenous peoples as a traditional food throughout Canada.

“Bannock is viewed as an important food for Aboriginal residents of Winnipeg’s North End neighbourhood, despite its historical associations with European settlers. Bannock is associated with family histories, cultural events and ceremonies, and food security. Bannock is seen as having a deep connection to identity’ (Cyr & Slater, 2016, pg., 59).

“Bread – white, store bought bread is not the way of our people, it’s not! Bannock is the way. It’s a staple food, it gives you strength it gives you energy. It just makes you strong. It’s so important to eat bannock, to have bannock’ (Cyr & Slater, 2016, pg., 63).

Making Bannock

With literally hundreds and hundreds of recipes to choose from, I decided on a recipe I found in a publication called “Bannock Awareness.’ This publication was produced by The Ministry of Forests and Range in 2001 to commemorate Aboriginal Awareness Day, which is celebrated annually on the 21st day of June. “Bannock Awareness’ is a collection of favourite bannock related recipes and of little known facts about First Nations history and culture in British Columbia, the province where I live.

Basic Bannock Recipe – Fried or Stick-cooked

- 1 cup flour

- 1 tsp baking powder

- 1/4 tsp salt

- 3 tbsp margarine/butter

- 2 tbsp skim milk powder (optional)

Sift together the dry ingredients. Cut in the margarine until the mixture resembles a coarse meal (at this point it can be sealed it in a ziplock bag for field use). Grease and heat a frying pan. Working quickly, add enough COLD water to the pre-packaged dry mix to make a firm dough. Once the water is thoroughly mixed into the dough, form the dough into cakes about 1/2 inch thick. Dust the cakes lightly with flour to make them easier to handle. Lay the bannock cakes in the warm frying pan. Hold them over the heat, rotating the pan a little. Once a bottom crust has formed and the dough has hardened enough to hold together, you can turn the bannock cakes. Cooking takes 12-15 minutes. If you are in the field and you don’t have a frying pan, make a thicker dough by adding less water and roll the dough into a long ribbon (no wider than 1 inch). Wind this around a preheated green, hardwood stick and cook about 8 inches over a fire, turning occasionally, until the bannock is cooked.

Conclusion

Bannock is delicious!

And despite its ties to colonialism in Canada, bannock embodies Indigenous culture and identity, both past and present. Whether made of white flour or ground camas bulbs, on a stick or in a pan, with berries, birch syrup or butter, bannock is an important traditional Indigenous food. With deep ethnobotanical roots, bannock has been integrated into the lives of the many Indigenous groups in Canada, creating comfort and community during many uncertain times.

“Fill your heart with happiness and love before starting to bake or cook; this will be your secret ingredient that will make this recipe taste so good! Think of the smiling faces of your family and friends as they enjoy this wonderful bannock that you have taken the time to prepare with your own loving hands” ~ Kate Brant (Morin, 2009, pg. 62).

References

Ballantyne, E. (2014). Dechinta Bush University. Mobilizing a knowledge economy of reciprocity, resurgence, and decolonization. Vol. 3, No. 3, pp. 67-85. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society.

Bandringa, R. (1999). The Ethnobotany and Descriptive Ecology of Bitterroot, Lewisia rediviva Pursh (Portulacaceae), in the Lower Thompson River Valley, British Columbia: A Salient Root Food of the Nlaka’pamux First Nation (Master’s thesis). The University of Victoria. Retrieved January 18, 2108, from https://open.library.ubc.ca/cIRcle/collections/ubctheses/831/items/1.0099512

Bell, A. (2018, August 4). Bannock and Canada’s First Peoples. Retrieved January 18, 2018, from https://fooddaycanada.ca/featured-article/bannock-canadas-first-peoples/

Billson, J., & Mancini, K. (2007). Inuit Women Their Powerful Spirit in a Century of Change. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Blackstock, M. (2001). Bannock Awareness. Retrieved January 4, 2018, from https://www.for.gov.bc.ca/rsi/fnb/bannockawareness.pdf

Colombo, J. (2006, February 6). Bannock. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved January 18, 2018, from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/bannock/

Cyr, M., & Slater, J. (2016). Got Bannock? Traditional Indigenous Bread in Winnipeg’s North End. Chapter 4. Retrieved January 17, 2018, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311202983_Got_Bannock_Traditional_Indigenous_Bread_in_Winnipeg%27s_North_End

Gilpin, E. (2017, July 11). At ‘BigHeart Bannock,’ Resilience and Resistance in Food Made Well. The Tyee. Retrieved January 4, 2018, from https://thetyee.ca/Culture/2017/07/11/BigHeart-Bannock-Resilience-Resistance-Food/

Kuhnlein, H., & Turner, N. (1991). Traditional Plant Foods of Canadian Indigenous Peoples: Nutrition, Botany and Use. Amsterdam, NL: Gordon and Breach.

Long, L. (2015). Ethnic American Food Today: A Cultural Encyclopedia, Volume 1. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Morin, P. (2009). Banockology, A Community Collaboration of Stories, Art, Essays, Recipes and Poems about Bannock. Victoria, BC: Open Space Arts Society.

Turner, N. (1997). Food Plants of the Interior First Peoples. Victoria, BC: Royal BC Museum.

Palmer, A. (2005). Maps of Experience: The Anchoring of Land to Story in Secwepemc Discourse. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.