Leymus mollis (Trin.) Pilg.

Introduction

Grasses, along with many plant fibers, played a significant role in humanity’s ability to innovate and survive. All of our ancestors found innovation within their local context. As humans gained proficiency with tools and materials, grasses and other plant fibers were fashioned into cordage, containers, bedding, floor mats, clothing and more. Wherever people lived, they found ways to twine, weave, twist, tie, fold, stitch, bend, wrap, knot, braid, bind, and lace to make all types of items of domestic necessity or utilitarian beauty. On this side of the Bering Strait, cordage and basketry impressions have been found on sites as early as 12960 years ago, underscoring that plant-derived fiber technologies an earliest technical skillset. (Adovasio, 2016; 1)

I find this common heritage of innovation to be inspiring and humbling when noticing what exists in our shared environment in contrast with industrially produced items used today. When considering basketry, and woven materials, no wonder we are lost without a teacher. Without a teacher, we must begin at the lowest level of innovation, using whatever basic skills we may have to make sense of what can be obtained to make an object to meet a need.

Empathetically then, it is understandable that if a teaching of a skill, like a language, goes untaught, then the gap in the knowledge or skills widens, reducing overall cultural confidence and autonomy.

Realizing too that the materials available shape the skill, meaning the direct environment influences the outcome of the learned skill, and that the final product is also defined by the need, long experience with the available materials and developed skill would allow a person to be efficient at recreating desired items. Further, the maker, as skill progresses may add elements of story, aesthetic beauty and personal touches to an object. These modifications and innovations require a long relationship with the materials.

Too, time and experience are essential to observe which areas within your locality have abundant, quality materials and how harvesting year-to-year affects their growth and availability. While I haven’t yet found any record discussing how beach ryegrass harvest improves it’s growth the following year, it is understood that annual harvesting of basket sedge and bear grass in the Pacific Northwest contributes to better growth the following year. (Peacock, S & Turner, NJ, 2005; 122) Likewise, the same is documented for improved sweetgrass harvest (Kimmerer, 2011).

About the Grass

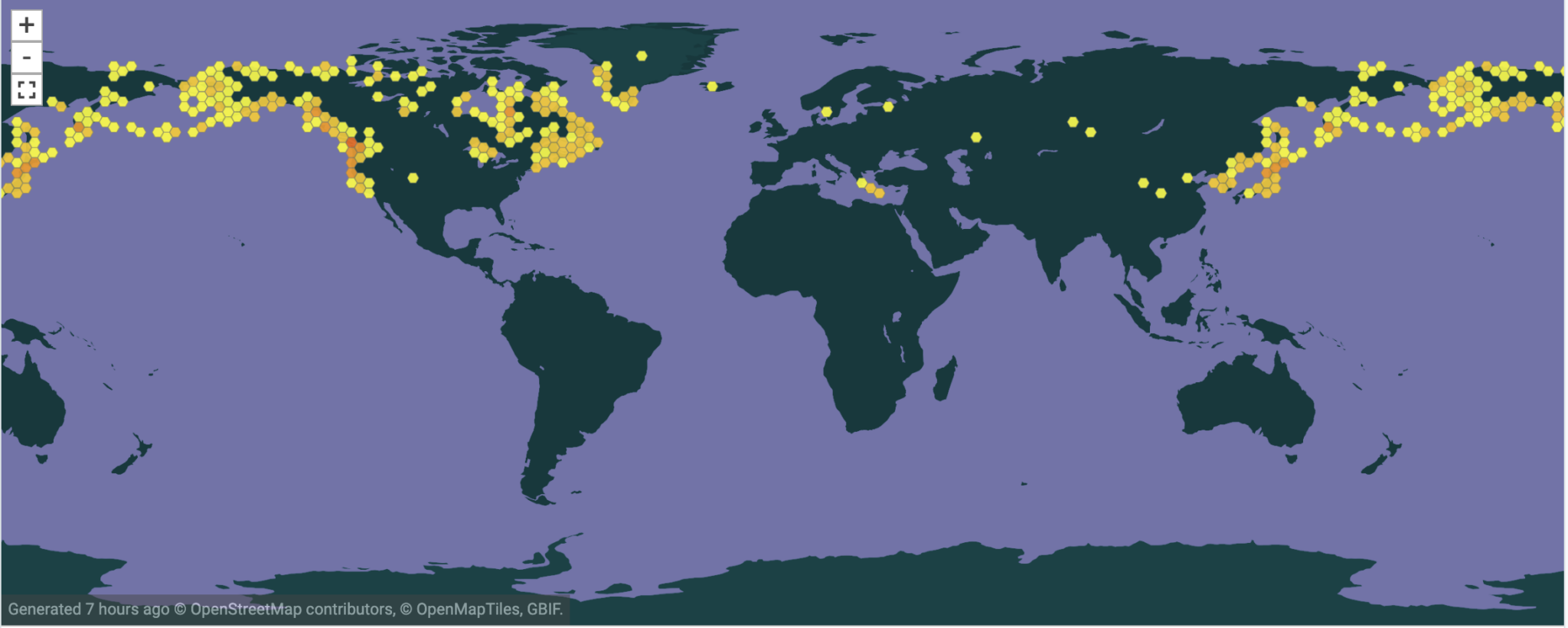

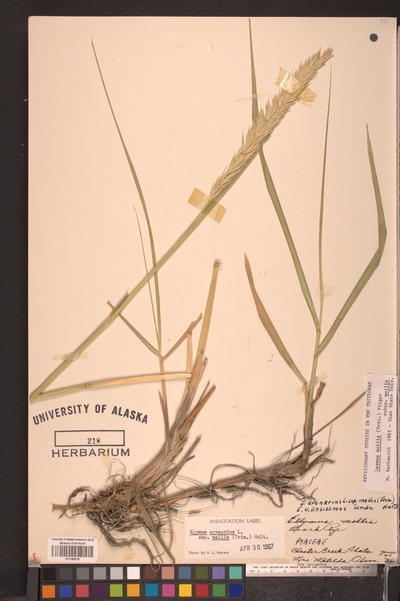

Scientific name: Leymus mollis and L. mollis (Trin.) Pilg. subsp. mollis (Poaceae)

29 scientific synonyms are listed on the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) including Elymus arenarius L. and E. arnarius subsp mollis (Trin.) Hulten.

English names: coarse seashore grass, beach ryegrass, beach wildrye, lyme grass, American dunegrass

This project will use L. mollis or beach ryegrass unless it is appropriate to use a synonym.

L. mollis is part of the grass family (Poaceae). Commonly along coastal areas, including beaches, dunes, cliffs, tidal flats and spits. While rarely found inland, it can also found along lakeshores. Strongly rhizomatous, it forms long drifts, often like a belt, along the high tide line of sandy beaches. (Hulten, E. 1974, 193) (Skinner et al. 2012, 332) A cultivar named ‘Benson’ in honour of Benny Benson, Alaska’s flag artist, was developed at the Alaska Plant Materials Center for use on coastal erosion control and reclamation projects. (Hunt P. & Wright, S. 2007).

The size of the plant varies depending on region and growing conditions. Plants can be short (less than 18″) or much larger. Plants I encountered were fairly large, with broad, firm blades longer than 20 inches where the culm and flower spike were around 3′ tall. Occasionally the base of the plant is tinged with pink, which reportedly indicate better plant fiber (Anaver, 2020). Grass blades are the part of the plant used as fiber and artisans have personal and regional preferences as to which size of blade (inner, outer) are be used for projects (Frontier Scientists, 2021).

In coastal South West Alaska, seeds from beach ryegrass are sometimes found in vole caches, also known as ‘mouse food’, and are called utugungssaraat (Yup’ik) (Fienup-Riordan, A. 2020, 196). It is recorded that in the English Bay and Port Graham (Alutiiq) area the bottom portion (likely the moist part under the outer blades?) of the beach ryegrass stems can be rubbed on cuts that are not healing. Alutiiq people also make scrubbers called taariq to use in the steam bath, or to clean dishes or clothing, from the coarse roots of L. mollis (Museum. A, 2021). Rita Blumenstein told that short tender sections of the rhizomes were occasionally eaten where she grew up on Nelson Island (Klebesadel, L.J, 1985, 33).

L. mollis is considered the most durable of the grasses and is the preferred type for making items meant for long lasting use. This plentiful grass is strong due to its waxy cuticle that protects the plant from desiccation in the salty, windy seashore conditions. (Yuungnaqpiallerput, Part 7, Inset: Gathering Grass, 2008). L. mollis is traditionally collected in the late fall, after all other work is done and after the weather had started the natural curing process. It was time to gather the grass when it changed colour, from green to pale golden brown, after the first frost and in good weather. Gathering large amounts of this grass (all grasses really) was an important task and mainly belonged to women, who would spend days gathering together. Depending on the locality, grass was collected, stored and dried in different ways. For example, Ms. Bluemenstein, also an established expert basket weaver explained that grass blades collected at 3 distinct times of years had physical differences that destined the grass to be used for specific purposes (i.e. basketry vs. cordage) (Klebesadel, L.J, 1985; 34).

Traditionally, grasses were twined, which is a kind of twisting weave, to make containers for specific purposes with different techniques (open weave, tightly woven or in-between), rugs or mats of different thicknesses and other items. Braiding or plaiting is also used to make cordage, for ropes or dog harnesses. (Yuungnaqpiallerput: 2008). Grasses can be split and dyed to make thinner, more detailed projects. The popular, recognizable style of coiled basketry, or mingqaaq (Yup’ik) or hagi (Illiamna and Outer Inlet Dena’ina) (Kari, P. 1995, 103) uses a needle to wrap the fibers and is different from twining. Basketry was also adopted as a commodity to appeal to traders in the late 19th century (Lee:2004) and this highly prized art form is still practiced today as a source of income for Alaska Native women (Lee, 2003).

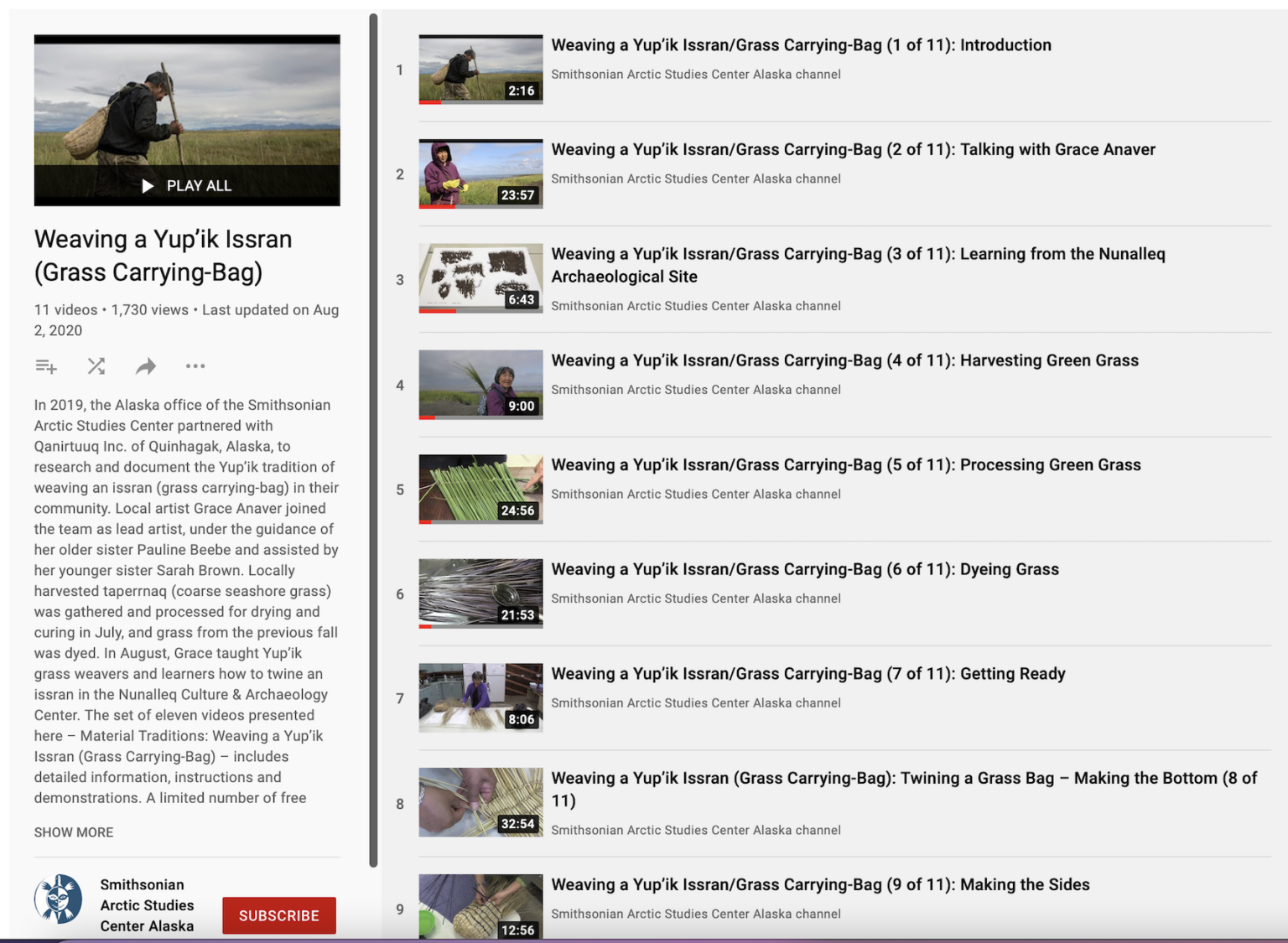

Nowadays, our changing climate affects the grass collecting season. In Southwestern Alaska, winters can be too wet and rainy instead of cold and clear, causing the grass to mildew and rot. (Anaver, G. 2020: part 2/11, 8:08). Collection and drying times are moving earlier in the year, gathering while the grass is still green so that the collector can have more control over the quality of the drying and curing. (Anaver, G. 2020)

Learning to Work With the Grass

I was inspired to follow the 11 part video series ‘Weaving a Yup’ik Issran/Grass Carrying-Bag’ with local artist and culture bearer Grace Anaver of Quinhagak, Alaska. Anaver demonstrates how to collect, dry, use and care for the coarse seagrass project. She teaches viewers and workshop students how to twine an ‘issran‘, a medium size carrying bag with an open weave traditionally used to gather foods like spring greens.

My project takes place where I currently live, in Anchorage, Alaska, a city of nearly 290,000 residents with diverse heritage. L. mollis grows along the coast here too, and while not recognized as a major fiber for the Dena’ina people pre-colonization, it was still useful to those who had access to it. The lands that are now considered Anchorage were part of seasonal hunting, fishing and trading lands of the Dena’ina people of the upper inlet. Here, birch bark is abundant and was the preferred local material for storage containers. Grasses, including L. molllis were used to weave colourful mats, thatching and door curtains. (Kari, P. 1995) In other parts of coastal Alaska, where birch bark and spruce roots were not plentiful, L. mollis was an essential fiber for making elaborate, innovative containers and clothing of all kinds, especially for the Aleut, Alutiiq, Inupiat and Yup’ik peoples who developed extensive, culturally distinct styles of baskets, carrying and storage bags, cordage, and clothing.

Some Indigenous names for L. mollis

taperrnaaq/taperrnat – Yup’ik singular/plural for L. mollis coarse seagrass, seashore grass.

Grasses, are collectively known as can’get in Yup’ik (Fienup-Riordan et al.:2019:300) and refer to plants in the Poaceae family and also the Sedge family (Cyperaceae).

tl’egh – According to Tanaina Plantlore, tl’egh means sedge and the Dena’ina classified L. mollis as a sedge (Kari, P. 1995: 103). Likewise, in the Dena’ina Topical Dictionary, there are several names for grass-like plants though none are specifically attributed to L. mollis. However, there are several names for coarse sedges (Cyperaceae) where tl’egh is the root word for sedge, or wide grass. Also listed is coarse tidal sedge, vantudushi, or ‘one that the tide goes up to’.(Kari, J. 2013: 53)

weg’et – Alutiiq for beach seagrass (Museum, A. 2021)

Gathering the Grass

“Our ancestors urged them to work hard to gather grass before there was snow on the ground, the grass that would be twined together, grass for boot insoles, ones they would use for everything, before Ellam Yua [the Person of the Universe] covered the land with his large hand, Ellam Yuan unalvallraminek nuna pategpailgaku, as they say. “ ~ Yup’ik Elder Paul John of Toksook Bay, July 2007 (Fienup-Riordan et al.: 2020: 3)

While I was looking forward to learning to twine a beautiful carrying bag, I wondered about access to beach ryegrass here in the context of the city. Anchorage sits on a high shelf of land above the inlet, and access to the coast is separated by the railroad, the airport, residential neighbourhoods and other developments. While the Coastal Trail connects downtown to Kincaid park, steep bluffs and mud flats combined with dramatic tides make the coastal interface an adventurous, if not dangerous endeavor. Few safe public access points exist, and determining which of those would have abundant L. mollis would be as much of a challenge as learning a new skill.

As I strategized for good locations, I also considered how access to materials affects Alaska Native women from around the state who have relocated to Anchorage from villages. How challenging is it to maintain cultural ties to this type of traditional knowledge when you move away from your materials and locality? In 2000, Anchorage became known as the largest Native Village in the world when 34%, or approximately 12500 people, of Alaska’s Native then total population made their home in Anchorage, and more than 60% were women (Ann Fienup-Riordan in Lee, 2003; 586).

It is possible to buy cured, dry beach ryegrass within Anchorage, and it is understood by artisans that grasses from some regions are more desirable than others. Basket weaver Melissa Berns of Kodiak Island recounts her experience purchasing grass for her projects from sellers either at the Alaska Federation of Natives craft show or from sellers at the Alaska Native Hospital. (Scientist, F. 2011; ‘Collecting and Curing Grass’, 3:20-3:33). Once she began collecting and curing her own grass, she notes how her appreciation for the skill deepened.

I was curious to see if it would be possible to gather L. mollis here in Anchorage.

I gathered grass 4 times, seeking a location with abundant grass and public, easy access. I used satellite imagery on google maps to help me determine possible access points to areas with a coastal habitat suited for L. mollis. My criteria was fairly straightforward; be in town, require less than 3 hours total time, and no unnecessary risks or trespassing.

1. August 30th, 2021 at the small boat launch parking area at Ship Creek

The grass here was strong, glossy, a little damaged with litter caught in between the grasses and sedges. There was a lot of L. mollis, but it was not easy to access. It mostly grew at the base of the rocky embankment which was difficult to walk on and the mud at the bottom of the embankment was soft. It was a juxtaposition of industrial activity with sounds from the port of Anchorage and passing trains next to the clear view to the mountains and the treacherous mud flats.

From watching the videos, I understood that I would need three large handfuls of dried grass to complete the project. On this day I collected 2 bunches of grass which dried to be much less than a single handful of grass.

2. September 12th, 2021 at the 1st public access parking area near the bridge over Ship Creek on Small Boat Launch Rd

I went back to the mouth of Ship Creek, this time trying the areas closer to the bridge. The tide had just turned to go out so the land was still wet. Because of this, I opted to cross the bridge and pick on the other side where the land was a little higher and I had seen someone fishing the last time I was there. The picking was easier over there but still, the grass was most abundant right at the edges of the embankment which put me very close to a railroad storage property. Also, where it grew in drifts closer to the river, the mud was so slippery that I did not feel stable near the water. I immediately felt that it would be foolish for me to walk towards the edge of the mud. To be safe, I picked along the edge of the road and embankment. I believed I was on public land because of the high water line. A security guard stopped his truck to talk to me and asked me what I was going to do with the grass. He seemed genuinely interested as I explained about how I was learning how to use it to weave a kind a basket. I asked him if it was ok for me to be there and he totally agreed it was. Later, when I looked at property maps and it appears as though the boundaries for the railroad properties extend all the way across Ship Creek and into the inlet so I’m not sure anymore.

3. September 19th, 2021 at Kincaid Beach

This area is part of the Anchorage Coastal Wildlife Refuge which extends from Point Woronzof to Potter Marsh. Getting to this location took the most effort because of the elevation change. To get to the beach access, you follow the winding paved trail from Kincaid Chalet that traverses the steep slope. Going down isn’t that difficult, though it gets a bit unstable once you reach the beach access path, where it narrows to a single file sandy, dirt trail. I felt self conscious gathering the grass as it was busy at the beach that bluebird day. The walk back up the hill was long, doable but long.

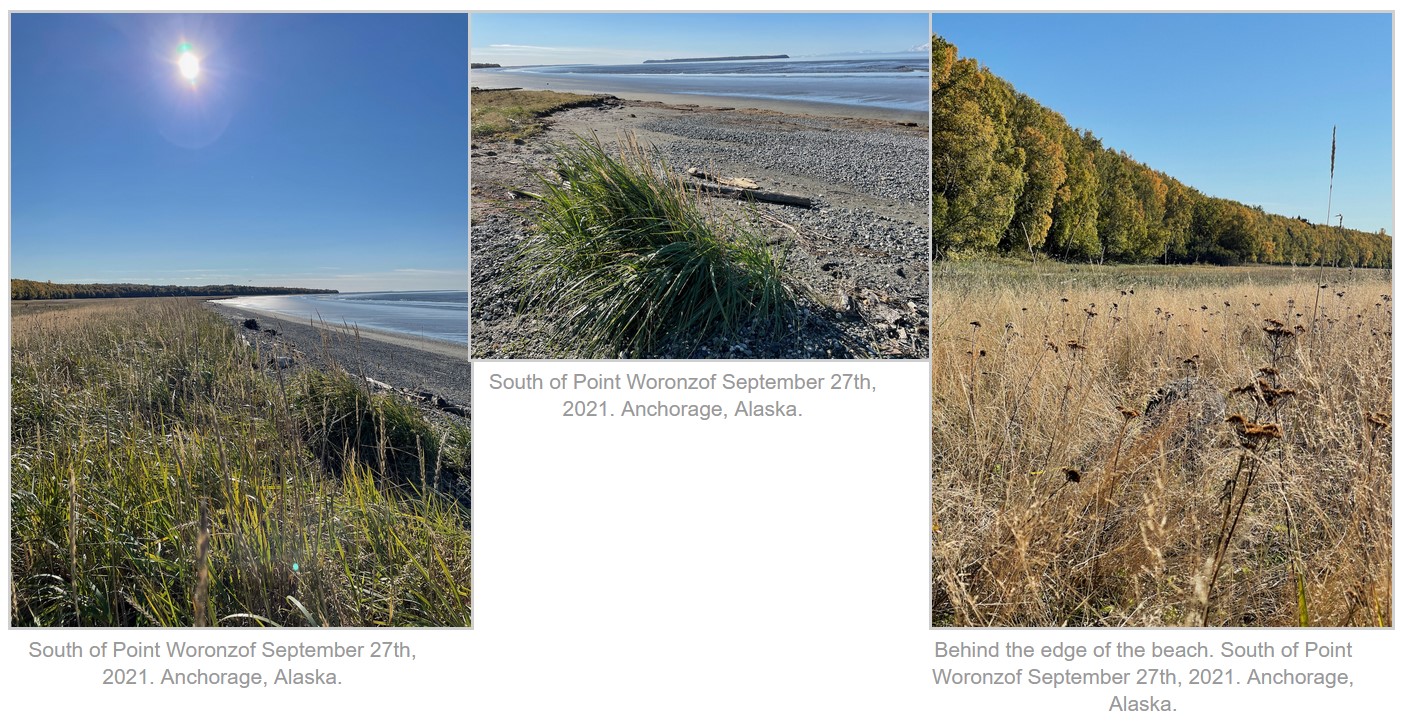

4. September 27th, 2021 about 1 mile south of Pt. Woronzof beach access point

This was by far the most enjoyable of locations to pick. It is also part of the Anchorage Coastal Wildlife Refuge. It helped that this late September day came with a cloudless, deep blue sky, light breeze and a warm sun. The tide was going out so I knew I had plenty of time to gather and make it back around the corner. (High tide can go all the way to the edge of the bluff, leaving no room to walk on the beach). I hadn’t been to this part of the point before so I didn’t know what to expect. L. mollis followed the edge of the beach facing the inlet and on the other side grew a meadow with other grasses, yarrow and beach greens.

Here is a link to a video I made here while picking grass. It’s just me picking grass and talking about it.

Drying (or Curing) the Grass

Grass to be used as a fiber is not brittle. Based on finished baskets I have observed and handled, well-cured grass becomes uniformly pale-straw coloured without any spots or blemishes. Ideally it retains a sheen, and becomes softer with time and yields to gentle twisting or manipulation. Having not transformed green grass into this kind of gold before, this was new territory for me and without touching finished grass, I’m not certain I achieved the ideal.

I tried different techniques, but ultimately the weather – that is the temperature, the moisture in the air and available sunlight – determined the success of the process.

Grace Anaver provides detailed yet simple instructions that are clear:

-Do not let the grass get wet while it is drying.

-Protect it from moisture so that it doesn’t get spotted or ruined by mildew.

-If you cannot keep it dry, freeze it until winter then proceed with drying in the frozen air where the weather will do all the work for you.

Once source instructed that fresh grass should be bundled in a towel to help it sweat and change colour (Alutiiq Museum, 2021: Weaving). I tried this technique with the Kincaid collection of grass. Unfortunately, this grass had some minor spotting and after one night wrapped in a towel, the spots spread it to other parts of the grass. It was very disappointing. It made me wonder if this technique worked better earlier in the season, before long rainy periods start leaving mildew on the grass blades? Or maybe the wrapped grass needed to be in the warm sun, letting it cook a little? This is a question a teacher could answer.

I have a south facing table under the eave of our garage where I was able to spread out the grass. For the first part of September there was abundant sunshine and clear days. After the 19th, it began to be rainy and windy. On September 24th we had heavy wet snow accompanied by wind and rain. I brought in all the grass and decided to twine all the grass I had into fans as shown in the video, mainly to protect the grass from damage as I moved it between indoors and outdoors. I tried to keep the collections separate. The August 30th collection was already a beautiful straw colour and completely dry so I simply stored it upright in the house like a bouquet.

Observations

Fresh grass contains a lot of moisture and shrinks a lot. Out of curiosity I dried 100g pieces of fresh grass – 73 blades of grass.

Over the next few days it dehydrated rapidly.

Sept. 19: 100g

Sept. 20: 87g

Sept. 21: 70g

Sept 23: 64g

Sept 25: 53g

The grass begins curling into itself soon after it is picked, transforming from a flat blade into a cylindrical straw. As it curls, it may curl around another blade of grass. Once home, as I spread the blades out to dry, I needed to handle each blade again, separating those that had rolled together, and laying them out so that they remain separated.

7 weeks later…

Shortly after I gathered the last batch of grass from Point Woronzof and braided that green grass into fans, it became rainy, windy and cold so it was not possible to leave the grass outside at all. I kept it hanging in the house. It is remarkable to me to compare the differences in the grass. I suppose because it didn’t receive as much sunlight as the rest, the 4th collection never really changed colour. It remained greenish, though it feels the same as the grass that had longer to cure.

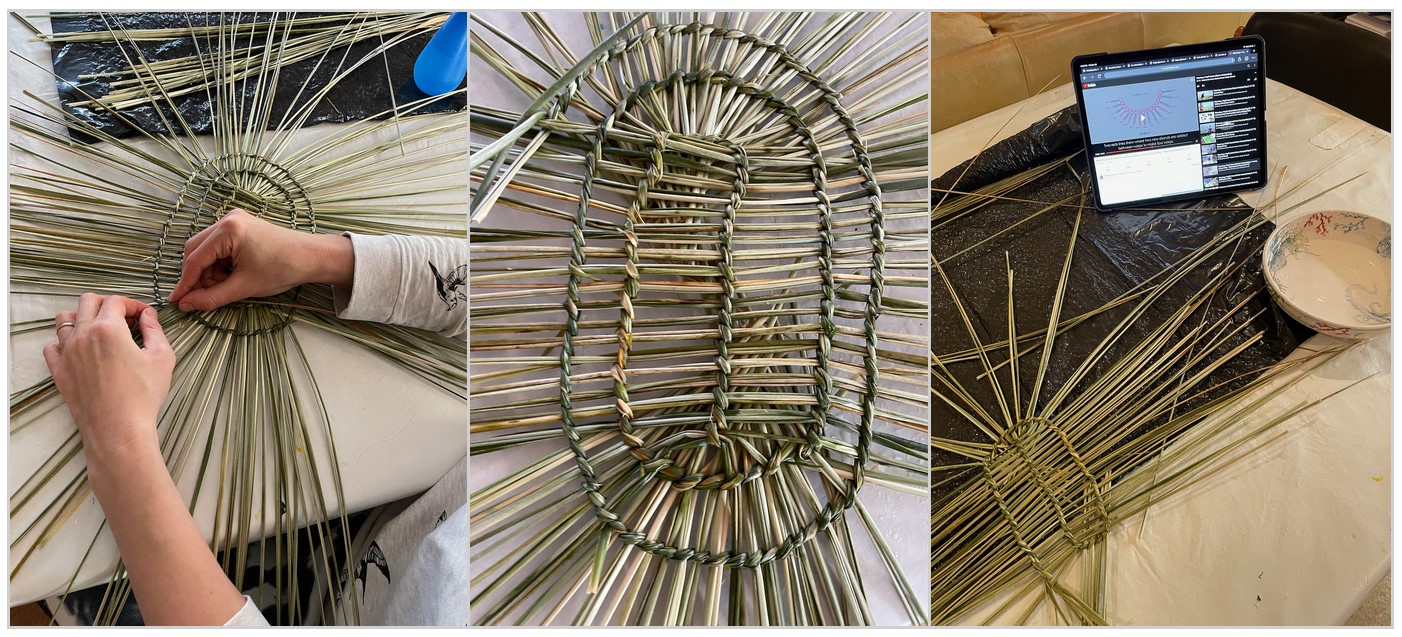

Making the Issran (Grass-Carrying Bag)

Ms. Anaver created a pattern for this based on a medium size grass carrying bag made by Natalia Smith of Hooper Bay, about 30 years ago. (Anaver, 2020, p7/11; 0:19-0:40). You begin by creating an oblong bottom, spiraling outwards from a long line, incrementally adding new warps as you turn the spiral. Using a pattern was incredibly helpful. I couldn’t see the bag in person but I was able to work “alongside” the workshop participants and compare my progress to theirs. During this video I paused, rewound, and rewatched several segments to view the pattern, help understand what was going to happen and if I was following the directions correctly.

I chose to work with the 4th collection of Point Woronzof grass which is why it is a little green instead of straw coloured.

Once I finished with the bottom turns, it was very helpful to watch and listen to Ms. Anaver describe how the bag takes shape. Watching her press down on the bottom helped me feel like I could do the same without damaging the bag. Her explanation on how to draw the warps closer together was also very useful. (Anaver, 2020: p 9/1; 7:40-9:00)

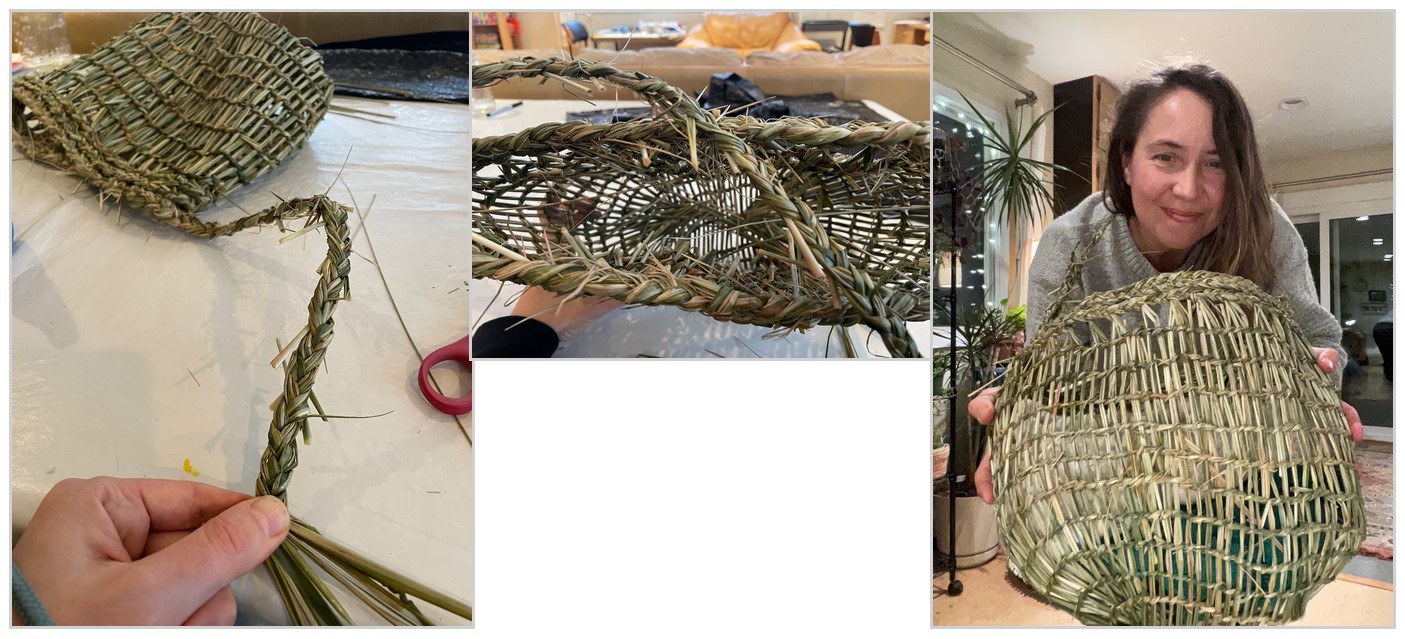

Making the sides was straightforward. However, at first I struggled with how to hold the project and maneuver my hands as I worked. Suddenly, I started using my hands in a way that felt smooth and natural. I twisted the weft with my right hand, keeping my left hand at the ready to hold the twist tightly open, then using my right hand, moved the next warp into position, twisting it, then passing the weft from my left to my right fingers to twist around the twisted warp holding it in position. Repeating as I went around. Once I found this rhythm, the project moved quickly. Perhaps had I been learning in person, I would have been able to mimic the movements better.

Reviewing the videos now, I can see this position modeled easily, but for whatever reason I missed it earlier as I was much more focused on following the pattern correctly.

How long did it take to make the bag?

I began soaking grass (~160 pieces) Friday morning. I let it soak for longer than 4 hours (closer to 6 hours) because it still seemed brittle to me to work with. I started the bottom Friday evening. I finished the bottom and began pulling up the sides Saturday afternoon and ran out of my first batch of soaked grass. On Sunday morning I began soaking more grass (~90-100?), and later in the day worked up the sides and ran out of grass again. On Monday I soaked ~120 pieces of grass, all I had left that was from this Pt. Woronzof collection and completed the sides. On Tuesday I finished the top and braided the strap.

In between work sessions I stored the bag project outside to freeze sealed in a large plastic bag. The extra grass was rolled up in a garbage bag which I tied at the ends with twist ties and a little clip to keep it closed in the middle. I didn’t run out of grass on Tuesday so I put the remainder outside to freeze. It took me about 5 days to complete the project, working for about 2 hours, more or less, each time.

Conclusions and Further Discussion

Nowadays, with a global cash economy at our fingertips, we make do without our hand-made objects like baskets, string or cloth. Like others participating in our modern society, I choose to purchase items ready-made for many reasons. In some cases, these items are hand-made by people from other parts of the world using skillsets unique to their culture or lineage for wages that may or may not be equitable, and certainly not always rightfully attributed.

Developing proficiency and a relationship with a seasonal cycle of natural materials is a lost language for many.

This is a long discourse to say that maintaining a cultural lineage or skillset of basketry requires consistent exposure, practice and education within a locality. For example, if I had a cultural tradition of making basketry requiring plant materials unique to my cultural locality, lineage and skillset, I can imagine how much would be lost through compounding separation and relocations from my lands of family origin which for me refers to Ontario, Canada, British Isles, Finland and beyond.

Finally, throughout the videos, all of the teachers and artists relay how important their physical connection with the material and locality is to them, how rewarding it is emotionally and psychologically to complete the cycle year to year, and how much they value their relationships to their teachers.

Sources

All photos by Oona Martin unless otherwise cited.

Adovasio, J. M. (2016). Basketry Technology: A Guide to Identification and Analysis (Updated ed. 2010). Routledge Press.

https://books.google.com/books?id=Ha4YDQAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

Anaver, G. (Presenter). (2020). Weaving a Yup’ik Issran/Grass Carrying-bag [series]. Smithsonian Arctic Studies Alaska Channel.

Fienup-Riordan, A., Reardon, A., Meade, M., Jernigan, K., & Cleveland, J. (2019). Edible and Medicinal Plants of Southwest Alaska: Yungcautnguuq Nunam Qainga Tamarmi All the Land’s Surface is Medicine. University of Alaska Press.

Garibaldi, A., 1999, Medicinal Flora of the Alaska Natives: A Compilation of Knowledge from Literary Sources of Aleut, ALutiq, Athabascan, Eyak, Haida, Inupiat, Tlingit, Tsminshian and Yupik Traditional Healing Methods USing Plants, Alaska Natural Heritage Program, Environmental and Natural Resources Institute, University of Alaska, Anchorage.

Hulten, E. (1974). Flora of Alaska and Neighboring Territories. Stanford, California, Stanford University Press.

Hunt P. & Wright S., (2007) ‘Benson’ Beach Wildrye Leymus mollis (Elymus mollis) Profile Sheet, State of Alaska, Department of Natural Resources, Division of Agriculture, Plant Materials Center, 5310 S. Bodenburg Spur Rd., Palmer, AK 99645-9706

Jones, A. (2010) Plants That We Eat: Nauriat Nigiñaqtuat. 2nd Ed. University of Alaska Press.

Kimmerer, R. (2011). Restoration and Reciprocity: The Contributions of Traditional Ecological Knowledge. Human Dimensions of Ecological Restoration: 257-276.

Klebesadel, L.J, (1985) Beach wildrye: characteristics and uses of a native Alaskan grass of uniquely coastal distribution. Agroborealis Volume: 17 Issue 2 ISSN: 0002-1822

Langdon, S. J. (2014). The Native People of Alaska: Traditional Living in a Northern Land (5th ed.) Greatland Graphics.

Lee, M. (2003, Summer/Fall). “How Will I Sew My Baskets?”: Women Vendors, Market Art, and Incipient Political Activism in Anchorage, Alaska. The American Indian Quarterly: Published by University of Nebraska Press, 27(3&4), 583-592. https://doi.org/10.1353/aiq.2004.0081

Lee, M. (2004). Weaving Culture: The many dimensions of the Yup’ik Eskimo mingqaaq. Etudes/Inuit/Studies, 28(1), 57-67. https://doi.org/10.7202/012639ar

Museum, A. (2021). “Alutiiq Word of the Week Archive – Search.” Word of the Week Archive. Retrieved December 3, 2021, from https://alutiiqmuseum.org/word-of-the-week-archive/search/results?site=1.

Museum, A. (2021). “Weaving.” Cultural Arts. Retrieved December 3, 2021, from https://alutiiqmuseum.org/learn/the-alutiiq-sugpiaq-people/cultural-arts/weaving.

If you entered a typical Alutiiq household of the seventeenth century, fine weaving would surround you. Grass mats would line sleeping benches, cover the walls, and hang in doorways. Woven containers for collecting, storing, and cooking food would surround a central fireplace. People would wear woven socks, mitts, and caps. A mother would hold her baby in a woven carrier. And the rafters would hold woven tools, nets for fishing and birding, and braided lines for harpoons and boats.

Scientists, F. (2011). “Alutiiq Weavers – Frontier Scientists.” 6 part video series and reference materials; in partnership with Alutiiq Museum in Kodiak, Alaska. Uploaded to Youtube in 2011. Retrieved December 5, 2021, from https://frontierscientists.com/projects/human-history-science/alutiiq-weavers/.

Skinner et al. (2012) A Field Guide to Alaska Grasses, Alaska Department of Natural Resources, Division of Agriculture, Alaska Plant Materials Center, Palmer AK. Education Resources Publishing an enterprise of Education Resources LLC. Arcanum Place, Georgia.

Peacock S & Turner NJ, (2005) “Solving the Perennial Paradox” in Keeping it Living: Traditions of Plant Use and Cultivation on the Northwest Coast of North America, University of Washington Press.

Yuungnaqpiallerput. (2008, June). Yuungnaqpiallerput – The Way We Genuinely Live – Masterworks of Yup’ik Science and Survival. yupikscience.org