Western Skunk Cabbage in Southeast Alaska

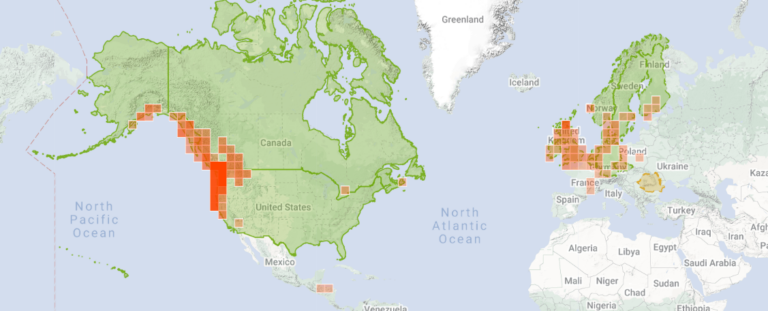

Lysichiton americanus Hultén & H. St. John also known as western skunk cabbage or “swamp lantern,” as it is referred to in Canada, otherwise known as western skunk cabbage or Lysichiton americanus, is a perennial, member of the Arum or Araceae family and grows primarily in temperate, coniferous rainforests like those of Dzantik’i Heeni, Alaska. It’s one of the earliest flowering plants of the spring. Skunk cabbage is related to the taro root and philodendron plants. It is protogynous, meaning it is a hermaphrodite that starts as a female, matures into a male and in the case of skunk cabbage, is pollinated by another species. The plant emits a skunky scent that attracts flies, beetles and other insects that help pollinate the plant. The pollen gets stuck to their feet and they dust other plants with it while they feed from plant to plant. The plant grows almost stemless, from one central rhizome, with leaves that can reach heights of five feet or more and the roots are incredibly deep and thick with the thick central cylindrical middle rhizome and many strands or roots coming out from all sides, almost like a really big green onion (from the bottom of the stem down into the ground).

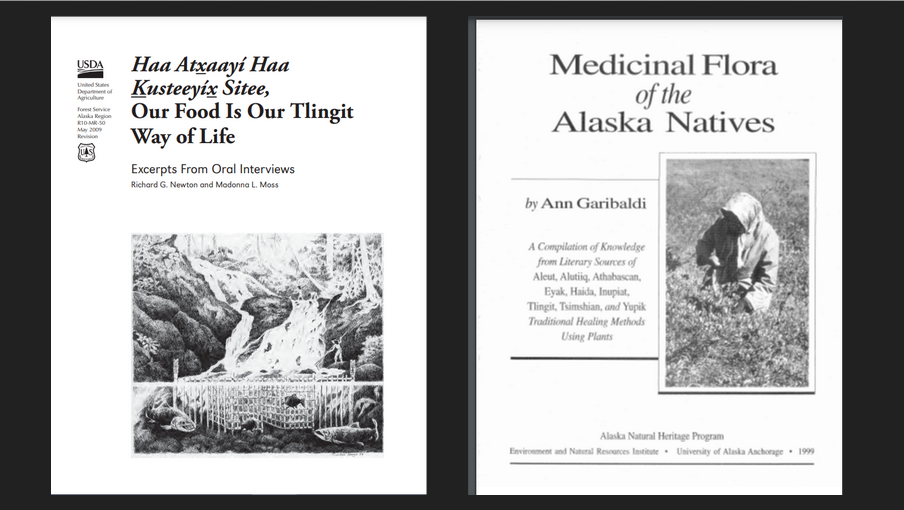

According to the Native American Ethnobotany Database, Lysichiton americanus has 111 different uses. Indigenous knowledge graciously shared by Tlingít Elders in Southeast Alaska, says that western skunk cabbage can be used to line an underground roasting pit, as a vessel for pickling, foraging or serving food, food storage and dried and ground to make medicine such as tinctures or tea (Newton & Moss 2009: 10, 12, 27, 28).

Another compilation of (literary) sources of Indigenous knowledge from multiple tribes and parts of Alaska, compiled by Ann Garibaldi, includes four tribes’ uses of the plant including use of the dried the roots for medicine by Alutiiq people, the treatment of colds by Athabascan people (although skunk cabbage doesn’t really grow in traditional Dena’ina territory) a cure for headaches, tuberculosis, infections, inflammation, lung trouble and hair growth problems by Tlingit people, and as a bed or ground liner under a birthing mother in Tsimshian culture (Garibaldi 1999: 98-99).

Most sources advise against eating the plant raw. As aforementioned, dried roots can be ground into flour and made into syrup or tea for medicinal uses. Tlingít people also use it for cuts, burns and infections. You can make a tincture from the dried roots for coughs or to clear mucus from the lungs or drink it like tea for respiratory and digestive ailments. In Wild Edible and Medicinal Plants it is explained that, “Tea made from dried roots has been used medicinally to relieve cramps, coughs, bronchitis, asthma and inflammation of mucous membranes,” (Biggs 2019: 12). Scott Kloos, author of Pacific Northwest Medicinal Plants, shares similarly, that it can be good for camps, spasms, bronchitis and asthma “brought on by stress or anxiety. ”(2017: 361). Kloos advises not to consume any of the plant raw as it contains calcium oxalate, which can damage the digestive tract and throat. Calcium oxalate is a needle-like crystal that can be injurious to the mouth, throat and stomach (Kloos, 2017: 361).

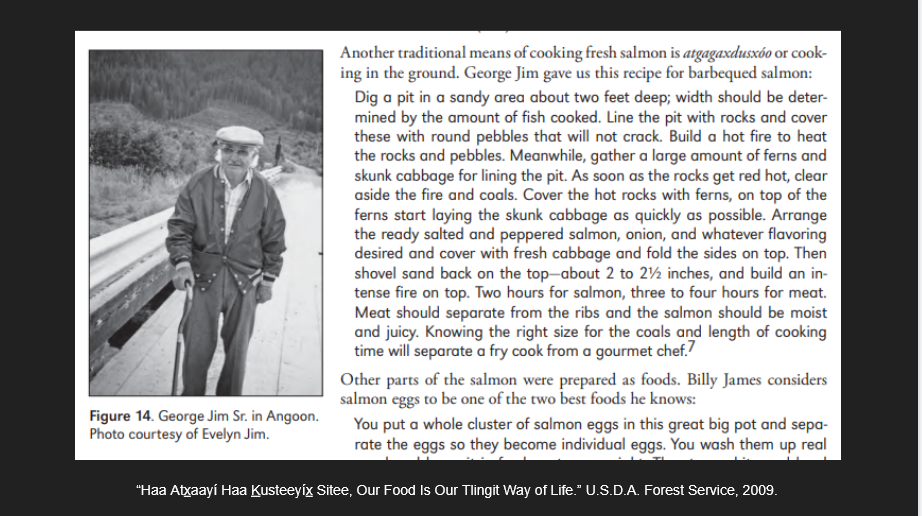

Since I am on Lingít Aaní (Tlingit land), and of Tlingít descent, I’d like to focus culturally on the Tlingít uses and terminology of the plant. The Lingít word for western skunk cabbage is x’áal’. There are even Lingít words for cooking methods that use skunk cabbage, like atgagaxdusxóo, which means “cooking in the ground,” and kanálxee, which roughly translates to “using skunk cabbage as a cooking pot,” (Newton & Moss 2009: 45-47). Another word in Lingít for pit lined with skunk cabbage is, áatʼl, which translates to “pit lined with skunk cabbage, used for storage,” (Twitchell 2017: 41).

For this first project, I chose to experiment with cooking underground using skunk cabbage. I think it’s a stretch to call this method a proper atgagaxdusxóo, but that was the original goal, at least. As I quickly found out, my plans and methods had to be altered according to the weather, location and time of year. As it was the end of September when I did this, and it is now the first snow of the year in the end of October, the skunk cabbage leaves were already on their way out for the season; many being yellow to brown and slumped over on the ground. I originally planned to do everything out North Douglas on a non-rainy day, because it was close to my house, but not riddled with mining chemicals (hopefully) like Sandy Beach is and I knew there was skunk cabbage in North Douglas. I gathered some skunk cabbage and got out to the beach with my supplies and realized there was no where I could easily dig a pit and build a fire as the beach is mostly rocks and the inland areas were also pretty dense and difficult to dig.

I decided to try again the following day, with the skunk cabbage I’d gathered previously and drove out to Lena Beach, which is on the other side of town by about 28 miles. It was raining and the area had no skunk cabbage as I ventured around looking for more, realizing I’d probably need more if I was going to build a proper pit. I then looked to the tall sedges growing along the creek and cut off about 8 blades and decided I’d use them to tie the skunk cabbage shut around the salmon almost like butcher’s twine.

I gathered uniform sized rocks along the beach each about three inches in diameter and round. This took only a few minutes as I only brought two small filets of salmon, about 6 ounces each. I attempted to dig a hole, but it was more of a shallow ditch as the ground was hard and unforgiving. I lined the hole with the rocks, covered it back up with sand and started a fire with some ripped up cardboard and firewood.

Once the fire had been burning for about 30 minutes, to get the rocks below hot and fire steady, I moved the fire wood over to one side with my shovel, removed the top layer of sand from the rocks and rearranged the “pit” by moving the top layer of rocks, placing the salmon in it’s skunk cabbage pouch on the bottom layer of hot rocks, and covering back up with the top layer of hot rocks, sand and then burning firewood again. The salmon filets were small, so I only let them cook for about 25 minutes; which was too long as the fish was slightly overcooked, but luckily still moist. The timing of the cooking process was based on my experience cooking roughly the same amount of salmon in a 350 degree oven for about 25 minutes.

After 25 minutes passed, I moved the burning firewood to the side and dug up the salmon wrapped in cabbage. It was wrapped in three layers of leaves and tied off with sedges, but I didn’t think about the heat making the leaves more fragile and my shovel pierced the leaves, causing the fish to get sandy. One filet was fine, but the other got pretty sandy, so I had to brush it off to eat it, but the texture was pretty good, the flavor was simple and pride, even in a sandy overcooked filet of salmon, cooked in the ground (and the rain!) were enjoyable.

My supplies were minimal, as I already had everything on hand, except for firewood, so I purchased a few bundles for $18.90 total. I had steelhead in my freezer and the other ingredients I used: onion, lemon, salt and pepper. I marinated the salmon ahead of time and brought it in some tupperware with a side of herring egg salad with pickled beach asparagus and some camping cutlery and just ate the salmon right off of the skunk cabbage leaf, propped up on a box I’d used part of to start the fire.

If I were to do this again, I have some ideas for more accurate cooking time and temperature. I would bring a thermometer, just out of curiosity next time to see how hot the pit gets and adjust the cooking time depending on the size or amount of fish. Additionally, I’d like to try and dig a deeper pit and do the actual lining of the pit with the skunk cabbage leaves, instead of making a pouch; although the results were still pretty good. I’d also choose another location for a deeper pit and ideally a day that it is not raining as it became challenging to keep the fire going and made it less enjoyable because I was rushing to get out of the rain instead of really trying to be present with the process. I also recommend bringing company. It felt very counterintuitive to attempt a traditional practice without any relatives or loved ones to share the food with, but due to timing, I had to pick a day where arranging with others was difficult.

References:

Biggs, C. R. Wild Edible & Medicinal Plants: Alaska, Canada & Pacific Northwest Rainforest. (Juneau, Alaska: Asia Printing Co, Ltd, 2019), 12.

Elpel, Thomas J. Botany in a Day: Herbal Field Guide to Plant Families of North America (Pony, Montana: Hops Press, 1996), 184.

Garibaldi, A. Medicinal Flora of the Alaska Natives: A Compilation of Knowledge from Literary Sources of Aleut, Alutiiq, Athabascan, Eyak, Haida, Inupiat, Tlingit, Tsimshian, and Yupik Traditional Healing Methods Using Plants. University of Alaska Anchorage, (1999), 98-99.

Kloos, Scott. Pacific Northwest Medicinal Plants (Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, Inc.), 360-361.

“Lysichiton Americanus: Yellow Skunk-Cabbage.” The Jepson Herbarium. University of California, Berkeley. 2006. <https://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/eflora/eflora_display.php?tid=32349>

The Native American Ethnobotany Database. (http://naeb.brit.org/uses/species/2337/ last accessed October 15, 2022.)

Newton, R. G. & Moss, M. “Haa Atxaayí Haa Kusteeyíx Sitee, Our Food Is Our Tlingit Way of Life.” U.S.D.A. Forest Service, 2009.

Twitchell, X’unei Lance. Tlingit Dictionary. (Juneau, Alaska: University of Alaska Southeast, Goldbelt Heritage Foundation, 2017), 41.

Willson, Mary F., and Paul E. Hennon. “The Natural History of Western Skunk Cabbage (Lysichiton Americanum) in Southeast Alaska.” Canadian Journal of Botany 75, no. 6 (1997): 1022–25. https://doi.org/10.1139/b97-113.

Project presented in December 2022.