Update: Listen to the project on KTOO: Garden Talk: Why silverweed is ‘a beloved plant all throughout the Pacific Northwest’!

Abstract

Potentilla anserina L., commonly known as silverweed, is a short herbaceous perennial found in various habitats across the holarctic. This report takes a look at the ethnobotanical significance of silverweed, exploring its diverse cultural uses and management practices, especially in the context of the Pacific Northwest Coast. The report also suggests the potential for reintroduction into contemporary gardens as a means of providing a valuable and culturally relevant food source.

What is Silverweed?

Potentilla anserina L., commonly known as silverweed, or tséit in Tlingit, is a short herbaceous perennial in the rose family, Rosaceae. The genus name, Potentilla, comes from the latin potens meaning powerful while the specific epithet, anserina, comes from the latin for goose. (Missouri Botanical Garden, n.d.) Both of these names offer a preview into the ethnobotanical and ecological background of this plant.

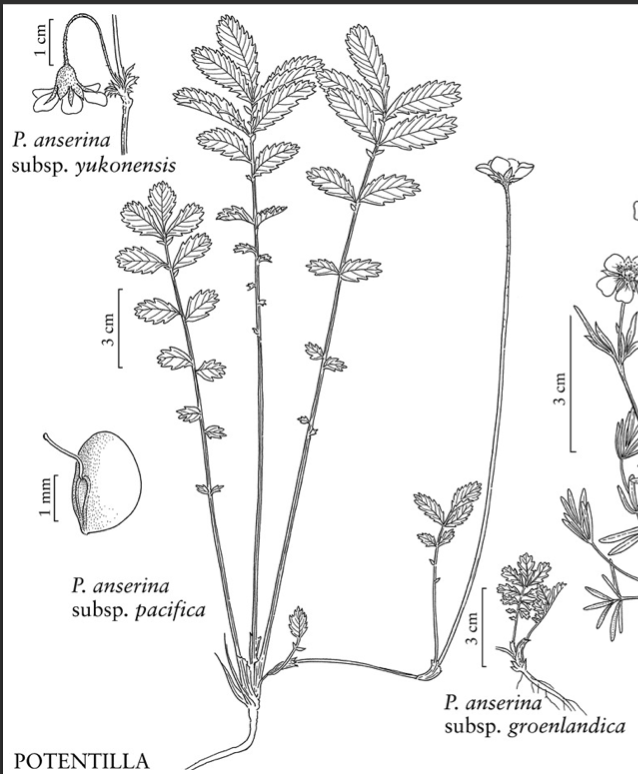

Silverweed is a particularly hardy, stoloniferous plant that is native to a range of habitats throughout the northern hemisphere. These habitats include but are not limited to salt marshes, prairies and riparian zones. It is especially known for its salt tolerance although the plants are not technically halophytes as higher concentrations of salts become a limiting factor in growth. The distinct pinnately compound leaves with silvery undersides, reddish stolons and vibrant yellow flowers make for easy identification of this species. (Wildflower Center, 2014; Kim, 2022, p.1)

Scientific nomenclature and therefore classification around silverweed remains a matter of debate. For example, P. anserina L. can be found listed at Argentina anserina (L.) Rybd. depending on where you look. As silverweed is an aggregate species synonyms include possible subspecies such as P. anserina ssp. pacifica (Howell) Rousi as opposed to P. pacifica or even Argentina egedii.

As a matter of clarification, this essay will use P. anserina L. to indicate any of the possible subspecies. All included search terms used for research as relates to nomenclature are as follows: Potentilla anserina, Potentilla pacifica, Argentina anserina, Argentina egedii, silverweed, and brisgean. (ITIS; Chevalier 2014)

Silverweed consumption and ethnoecology

Silverweed is edible from the flowers to the roots. While not all of these parts are equally palatable, both above and below ground sections of the plant have recorded uses in many cultures around the world. Although, it is the highly starchy roots of silverweed that are held in the highest regard. The nutritional content of silverweed has been shown to rival that of potatoes, supplying 29.5 carbohydrates and 136 kcal per 100g of dried and roasted silverweed. (Bishop, 2021, p.190) A paper looking into bread production augmented with silverweed found that the dried and powdered root can be substituted for wheat flour at around 5% as a means of enriching local diets with culturally relevant foods. (Ying, 2013, p.189)

In Scotland, where silverweed was once a staple food, it has been called, ‘Brisgean beannaichte an earraich – Seachdamh aran a’ Ghàidheil’ or, ‘Blessed silverweed of spring, seventh bread of the Gaels’. The plant was of such importance as a food source that people quickly returned to eating the roots during the potato blight. There is even evidence, at least from North Uist, of silverweed cultivation in Scotland. These cultivated roots were said to be of considerable size given their management. (Chevalier 2014, p.244; Hillman, 2018).

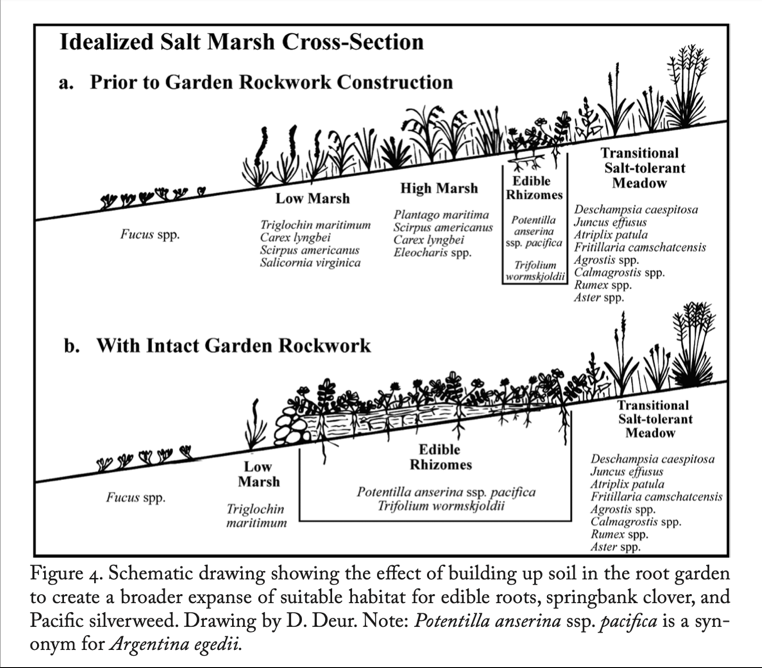

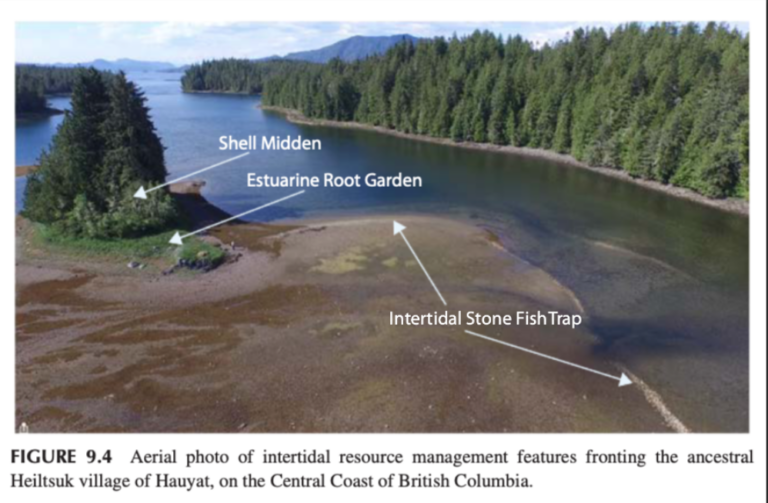

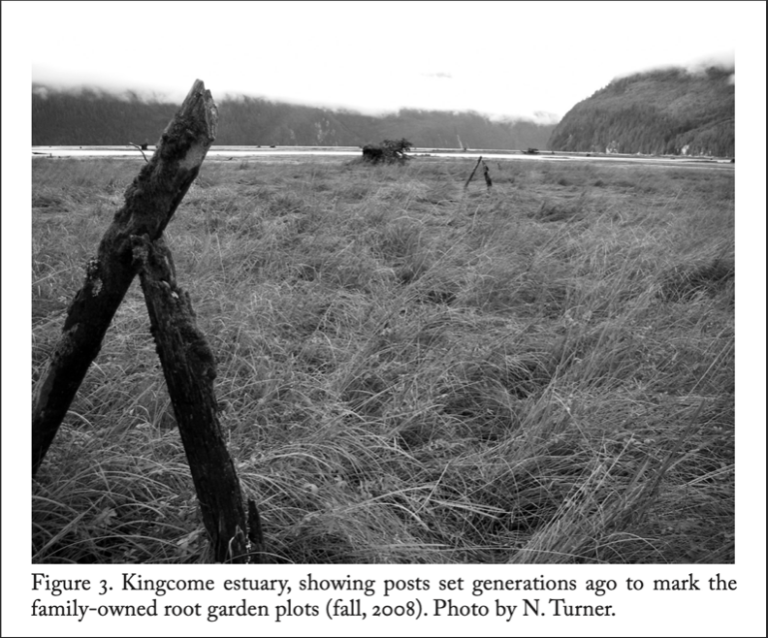

Indigenous cultures along the Pacific Northwest Coast have historically managed large plots of edible roots that naturally occur in the salt marsh. There are many varying cultural identities and practices along this coast, but in general, plots of silverweed and other preferred species were owned and managed by those with the highest social status. Co-managed species included Trifolium wormskioldii Lehm., Fritillaria camschatcensis (L.) Ker Gawl., and Lupinus nootkatensis Donn ex Sims. Sizes of these plots varied greatly depending on available land but were up to four hectares. These would have then been further subdivided into family/household plots and were of such importance that they would be guarded by hunters to keep waterfowl from consuming the plants. To aid in understanding how these plots were viewed in Kwakwaka’wakw culture, the Kwak’wala term used for these gardens is of interest here, taki’lakw, as it signifies that the soil is human made. This is in contrast to the term ts’o’yadi’, which would signify naturally occurring root grounds. (Deur, 2005, p.315)

Management of these estuarine plots was both of high cultural value and labor intensive. The estuarine garden plots were made by piling a stabilizing material, such as wood or rocks, oceanside so as to raise the soil level. This allowed for a much larger habitat for silverweed, which would normally be restricted to a thinner belt along the shoreline. Depending on the seasonal round of the plot owners, silverweed roots were gathered in either the spring or fall, while the plants were dormant. According to Adam Dick, clan chief of the Kwakwaka’wakw, he would help his grandmother and mother till the garden in spring, followed by weeding that continued throughout summer until the roots were ready to be harvested in the fall. These roots were then often sun dried and stored cold which helped to improve the flavor by reducing bitter tasting compounds such as tannins. Other management strategies employed by cultures such as the Kwakwakaʼwakw, Tsimshian and Haida include selective harvest, transplanting, removal of rocks and root propagation of desired species upon harvest. Quality and quantity were stressed as silverweed was an important trade item and food at celebrations, serving as a measure of status. (Deur, 2005, p.314; Lloyd 2011, p.42)

Quality control measures around the harvest and preservation of silverweed are intrinsically linked with the lifecycle of the plant. The roots of silverweed undergo significant physical and chemical changes throughout the year in response to the season. In spring, hair-like root growth is initiated from overwintered tubers as new leaves emerge, increasing in size until around July. Upon leaf maturation and flowering, attention is redirected towards energy storage in new roots. Both tannin and phenol content have been noted as possible agents behind the bitter taste sometimes encountered in silverweed roots. These too fluctuate in concentration depending on the season, with the lowest amounts recorded while plants are in dormancy or dried. (Lloyd, 2011, p.138)

Deciding where to harvest

For this project, silverweed was harvested on several occasions, in both the spring and fall. Finding a clean environment for harvesting silverweed was not as easy as I imagined. Given the extractive history of Juneau, Alaska, there are many sites with possible contamination. As I narrowed my search to salt marshes away from industry, I realized that suitable locations for harvesting quickly diminished, becoming one of the largest challenges in this project.

In Juneau, where the town is sandwiched between steep mountains and the ocean, flat land is a valuable resource. Consequently, meadows and marshes in the center of town are often developed. The Mendenhall Wetlands, which is the largest open, flat section of land in town, is home to the airport, sewage treatment center, and dump. As roots are where toxins, such as heavy metals, are most likely to accumulate, I proceeded with caution.

Mendenhall Wetlands (1st location)

The first place that I went to harvest was the Mendenhall Wetlands. In theory, this is a prime harvesting spot for silverweed as it fulfills multiple criteria found in the literature. The Mendenhall Wetlands is a salt marsh with a sunny aspect near a salmon-bearing stream. I have been to this location in the summer and had seen fields of silverweed, so I knew that finding roots would not be a problem. To avoid the possibility of pollutants as much as I could, I harvested from a group of silverweed at the farthest edge away from the river that runs by the dump.

To start, I found the dried leaves of silverweed amongst the grasses and sedge. They are a well-saturated dark brown and stand out in the rain against the faded golds and grays of other plants. Then, following the leaves back to the base of the rosette, I found the roots of the plant where the tiniest bit of green growth was showing. To harvest the roots and minimize breakage, I first used my hori-hori to pry up a section of earth, then slid the blade down into the soil half an inch from but parallel to the roots that I was aiming for. This action caused the mucky soils to release like a suction cup, and the roots were more easily wiggled out.

I can only imagine what the conditions would have been like for those harvesting in cultivated fields. Here, with such thick soils and a proliferation of competitive species, productivity was low. I am not great at keeping track of time when I am harvesting, but I would say that there were many more calories put into gathering than were gathered.

Looking over the Fish Creek site

Looking over the Fish Creek site

Aangooxa Yé (2nd location)

The second location I chose to harvest silverweed from was Aangooxa Yé, also known as Fish Creek. This is the site of a L’eeneidi village and gathering grounds, a pre european settlement. (Goldschmidt, 1998, p.39) There is no history of industry at this site, which allowed me to harvest without concern for my own health or those I would be sharing this with. Fish Creek, as the name suggests, is a popular spot to go fishing, so I knew that the plants would have been well-fed by the nutrients of decaying salmon. In terms of light conditions, the stream enters the ocean northward, so it is not the brightest of locations.

The soil here was significantly lighter than that of the Mendenhall Wetlands. I am curious if this could be at least partially attributed to the drifts of soil that stood higher above the water than the previous site. This allowed me to more easily pry up sections of soil and pull roots out. Roots in this location seemed significantly larger than those at the previous site. The coloration of the roots was also more akin to what I have seen in others images. I have returned several times to harvest from this area.

Consuming tséit

The first step to processing tséit is to clean the roots, which requires several washes. I first rinsed the roots while in the field and then, once home, I took several roots in my hand at once and rubbed them together between my palms. This action helped to scrub the dirt from the roots, but did cause some of them to break. However, the breakage was not a concern for me as the root fragments would be put to use in the second half of this project.

According to several Elders, boiling or steaming is the most common way to prepare tséit for immediate consumption, although the roots are often dried and bundled or stored in oil for the winter. Often it is then served with seal or eulachon oil, something that I do not have access to. (Newton, 2009, p. 24) In order to stay true to the theme, I chose to serve the tséit with some salt and basil oil that I had made the year before. The first batch was delicious. The texture was soft, and the flavor reminiscent of a nutty sweet potato. The second batch was significantly more bitter and astringent. This came as a surprise to me since the plants seemed more robust in size, and I therefore assumed the soil was more productive. Upon subsequent harvests at Aangooxa Yé, I found root quality to improve significantly after a week of freezing in the fall. Silverweed is a plant whose flavor can vary greatly depending on the site and timing of the harvest.

Propagating tséit

Silverweed is a relatively simple plant to propagate by a variety of means. When plants are left untouched, I have seen garden specimen produce upwards of 8 remets each. With assistance, these clones can be separated from the parent plant and used to fill in a garden site. In undisturbed sites, spread by stolons may constitute the majority of successful propagation as seedling recruitment is low and the seed must germinate within a year to remain viable. (Ericksson, 1998, p.529) Although it should be noted that without assistance these plants will spread wide and far before they fill in an area with any completeness. In addition, plants can be propagated sexually through seed and asexually through root fragments. This latter method is what I selected for use in this project in order to reflect methods documented in ethnographic reports.

A study on the ideal growing conditions of silverweed for the purpose of niche conservation and reintroduction was conducted in South Korea at the southern limit of the plants range. This study found that when analyzing habitat for silverweed the most important factors are a high light intensity, a moderate distance from a body of water on a slope, a high cation exchange and a coarse, sandy soil. (Kim, 2022, p.8) These findings are well aligned with the methods and outcomes seen in the estuarine gardens of the Indigenous peoples of the pacific northwest coast. Light intensity would be maintained by weeding, cation ion exchange capacity kept high through the tillage of organic matter, proximity and slope in relation to a water body idealized by means of rock walls, and soil texture augmented through the removal of rocks as well as tilling. (Deur, 2011, p.314) This is further echoed in the advice of Henry Katasse stating that, “…The best tséit are dug at the entrance of rivers and fish creeks – where the sun hits the area- they are sweeter in a sunny area.” (Newton 2006, p.23)

For my propagation method, I used the small, broken fragments of root that came off while rinsing the plants for consumption. These ranged in size from ¼ in. to around 2 in. and were kept in the soil they were dug from until potting them up. At the time of potting, many if not most of the fragments had initiated new above ground growth as well as some root development. Four, 1 liter pots were filled with a mix of the original estuarine substrate and sifted compost from the Jensen Olson Arboretum. The plants then remained in pots from the 27th of April until the 21st of June to develop stronger roots while the garden site was prepared.

The garden site for the silverweed was selected for sunlight exposure and visibility to the public. A section of the 100+ year old vegetable beds at the Jensen Olson Arboretum was thoroughly weeded and the soil sifted for rocks and competing roots. Total depth of tillage was around 2+ ft. in order to facilitate proper removal of large rocks and roots of Campanula rapunculoides L. No initial amendments were mixed into the soil upon planting. About a month later, mature seeds and bulblets of Fritillaria camschatcensis were planted along the border and a thin (approx. .5in) layer of compost was used to topdress.

At the beginning of November, after the silverweed had been in the ground for four months, I selected three plants to dig up. I was pleasantly surprised to find one of those three plants had produced a storage root over a foot long. I was unable to remove the roots without breakage so I can only imagine how deep the root must have gone. As silverweed roots do not have any obvious taper, no guesswork could be done to approximate the full length.

Conclusions

Silverweed is a plant that I have often overlooked. The plant is widespread and in such large communities that it can easily become a backdrop to other more novel or showy species. This project has shown me that those patches of silverweed may be much more than what meets the eye. Perhaps not too long ago, these salt marshes that I pass by on my way to and from work were areas of great importance and active management. Perhaps these plant communities, now tended by waterfowl only, were made to flourish by discerning mouths and loving hands.

A reunion between these unsuspecting plants and our gardens need not be a thought reserved for the classroom. As highlighted in the latter half of this essay, silverweed is by no means difficult to grow. With ample sun, water, and friable earth, silverweed can most certainly grace our abodes with their sweet, starchy gifts once again.

References

Bishop, R. R. (2021). Hunter-gatherer carbohydrate consumption: plant roots and rhizomes as staple foods in Mesolithic Europe. World Archaeology, 53(2), 175–199. https://doi-org.ezproxy.uas.alaska.edu/10.1080/00438243.2021.2002715

Chevalier, A., Marinova, E. V., Peña-Chocarro, L., & Griffin-Kremmer, C. (2014). SILVERWEED: A FOOD PLANT ON THE ROAD FROM WILD TO CULTIVATED? In Plants and people: Choices and diversity through time (pp. 242–249). essay, Oxbow.

Eriksson, O. (1988). Ramet behaviour and population growth in the clonal Herb Potentilla anserina. The Journal of Ecology, 76(2), 522. https://doi.org/10.2307/2260610

Deur, D., Turner, N. J., & Deur, D. (2011). Tending the Garden, Making the Soil. In Keeping it living traditions of plant use and cultivation on the northwest coast of North America (pp. 296–327). essay, University of Washington Press.

Fontefrancesco, M. F., & Pieroni, A. (2020). Renegotiating situativity: transformations of local herbal knowledge in a Western Alpine valley during the past 40 years. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 16(1). https://doi-org.ezproxy.uas.alaska.edu/10.1186/s13002-020-00402-3

Goldschmidt, W., Haas, T. H., & Thornton, T. F. (1998). Detailed analysis of the Juneau (Auk) Territory. In HAA aaní = our land: Tlingit and Haida Land Rights and use (pp. 38–44). essay, University of Washington Press.

Guo, T., Qing Wei, J., & Ping Ma, J. (2015). Antitussive and expectorant activities of Potentilla anserina. Pharmaceutical Biology, 54(5), 807–811. https://doi.org/10.3109/13880209.2015.1080734

Hillman, G. (2018, January 30). Silverweed (Potentilla Anserina L.). Silverweed (Potentilla anserina L.). Retrieved April 15, 2023, from http://foragerplants.blogspot.com/2018/01/silverweed-potentilla-anserina-l.html?m=0

Kim, S. H., & Kim, J. G. (2022). Implications of realized niche for the conservation and creation of Potentilla anserina habitat. Ecological Engineering, 179. https://doi-org.ezproxy.uas.alaska.edu/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2022.106610

Lloyd, T. A., & Turner, N. J. (2011, June 7). (dissertation). Cultivating the tekkillakw, the ethnoecology of tleksem, Pacific silverweed or cinquefoil (Argentina egedii (Wormsk.) Rydb. ; Rosaceae): Lessons from Kwaxsistalla, Clan chief Adam Dick, of the Qawadiliqella clan of the dzawadaenuxw of Kingcome Inlet (kwakwaka’wakw). Retrieved October 30, 2023, from http://dspace.library.uvic.ca:8080/handle/1828/3359?show=full.

Missouri Botanical Garden. (n.d.). Potentilla anserina. Missouri Botanical Garden Plant Finder. https://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/PlantFinder/PlantFinderDetails.aspx?taxonid=286390

Morikawa, T., Ninomiya, K., Imura, K., Yamaguchi, T., Akagi, Y., Yoshikawa, M., Hayakawa, T., & Muraoka, O. (2014). Hepatoprotective triterpenes from traditional Tibetan medicine Potentilla Anserina. Phytochemistry, 102, 169–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2014.03.002

Newton, R. G., & Moss, M. (2006). Haa atxaayi Haa Kusteeyix sitee = our food is our Tlingit way of life: Excerpts from oral interviews. U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, Alaska Region.

Wildflower Center. (2014, August 26). Plant database – Potentilla anserina. Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center – The University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved April 15, 2023, from https://www.wildflower.org/plants/result.php?id_plant=aran7

YING JI, JIE GANG, & WENZHONG HU. (2013). Quality of Bread Containing Potentilla Anserina L. Cultivated in China. Italian Journal of Food Science / Rivista Italiana Di Scienza Degli Alimenti, 25(2), 189–195.

Project presented in November 2023.